|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| SQMP ToC | 中文版本 首頁 |

|

My Shen Qi Mi Pu Project

Reconstructing all the music from the earliest surviving guqin handbook1 |

我的神奇秘譜項目

At a seminar in Beijing after completing Phase 1 2 |

In 1976, when I moved from Taiwan to Hong Kong, I began transcribing old melodies from the Shen Qi Mi Pu (Handbook of Spiritual and Marvelous Mysteries, 1425 CE). "Transcribing" meant taking tablature, which described most details of the actual playing (finger positions, stroke techniques and ornamentation) but did not directly detail the note values/rhythms, and putting it into staff notation, which required determining the possible note values. As described here, I began with melodies still played today, so that I could use these performances for rhtyhmic and melodic guidance.

Then, as I became more involved in this work I decided to learn all 64 of its melodies. So I organized it in the form of a project, with three phases.

Phase One: Initial analysis, transcription and recording of the music in Shen Qi Mi Pu (SQMP)

In 1991 I completed this phase. Results include my annoted translations of Zhu Quan's general preface and of his introductions to each melody (updated versions are most easily accessible via the SQMP Table of Contents); translations from other old books on qin lore and finger technique, in particular the various versions of Taigu Yiyin (it has so many diagrams and is so heavily annotated I have been able to put only a part of this important work online); a set of hand-copied transcriptions into staff notation of all the tablature in SQMP; and, after practice and analysis, my personal versions of all the music, recorded on six one-hour cassettes.

By this time I had begun attending guqin conferences in China, where I played my reconstructions. This led to my being invited to Beijing for the seminar mentioned in the image at top.

Phase Two: Comprehensive Analysis

The main aims of Phase Two are to differentiate various playing styles, to develop some theories on dating the music, to study further the historical and cultural contexts, and at the same time to continue trying to improve my ability to play the music.

The music in SQMP clearly pre-dates 1425 AD, almost certainly including Tang and Song compositions altered by performers of the various guqin schools which developed during the Song dynasty. Present interpretations at best reflect an amalgamated early style, and it may be impossible to delineate specific ones. Clues to follow include melodic and modal distinctions, differences in finger techniques and in the ways of writing them down, favored subject material, and perhaps the relationship of the music to lyrics in versions to which poetic text has been added ("qin songs").

Basic to the analysis should be comparing music in SQMP to Japanese court music (gagaku) as reconstructed by experts in the Tang Dynasty Music Research Project, originally at Cambridge University. Gagaku is said to preserve Tang dynasty court music, but as played today gagaku sounds nothing like any known Chinese music. As re-constructed by these experts, however, there are some potentially noteworthy similarities between it and early guqin music, which on a completely different basis claims to preserve Tang dynasty music. These similarities must be examined.

Another task is a more comprehensive study of early qin finger techniques, which are not always the same as at present. The two major direct sources for this information are Qinshu Daquan (1590 CE) and the compendium mentioned above of qin materials published at different times under such names as Taigu Yiyin and Taiyin Daquanqi. Zhu Quan is said to have edited and published one of the editions of this book and so, although his own edition does not survive, the other editions are good companion volumes to SQMP, which does not include such information.3

It is also essential to learn other guqin melodies which might have pre-Ming sources, as well as a number of the over 1,000 surviving Ming compositions (most of them modifications of earlier pieces), and to analyze these and other written sources for the clues they give to pre-Ming music. This in turn could shed some light on the interpretation of early Chinese music for other instruments.

When learning the pieces in SQMP I compared them with many other early Ming versions. I have written out transcriptions of and learned to play all the few melodies printed before the Ming dynasty, with the exception of You Lan (briefly discussed together with the melody Yi Lan); have published a CD of my interpretations of the 13 pieces not in or different from those in SQMP in the second major surviving collection of qin pieces, Zheyin Shizi Qinpu (>1505), as well as a book of their transcriptions; these all have lyrics added as though they should be sung, and so I have tried to study the relationship between the words and music in this handbook and also have learned about ten 16th century qin pieces with lyrics, more obviously intended for singing; and I have also reconstructed a number of additional qin pieces from 15th and 16th century qin handbooks.

Phase Three: Publication

This includes commercial quality recordings, a book with music transcriptions, and another book of commentary, translations, charts and so forth.

In 2000 I published my Shen Qi Mi Pu recordings as a set of 6 CDs, and the transcriptions as a set of three books of staff notation.

Summary

Phase Two is in fact open ended, so publication of results could take place at either an earlier or later stage. There is an immense amount of material available: much medieval Western music has been re-created from less detailed sources than are available for this earlier Chinese music.

With my festival job I had only been able to work at this project part time, but with the cancellation of the 2000 festival I have been able to put more time into this, particularly working on transcriptions from later handbooks, for comparative purposes.

I have also been doing performances and working on other qin projects as well (see, for example, my Outline Research Proposal).

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

1.

神奇秘譜 Shen Qi Mi Pu

Discussed in detail in this section

(Return)

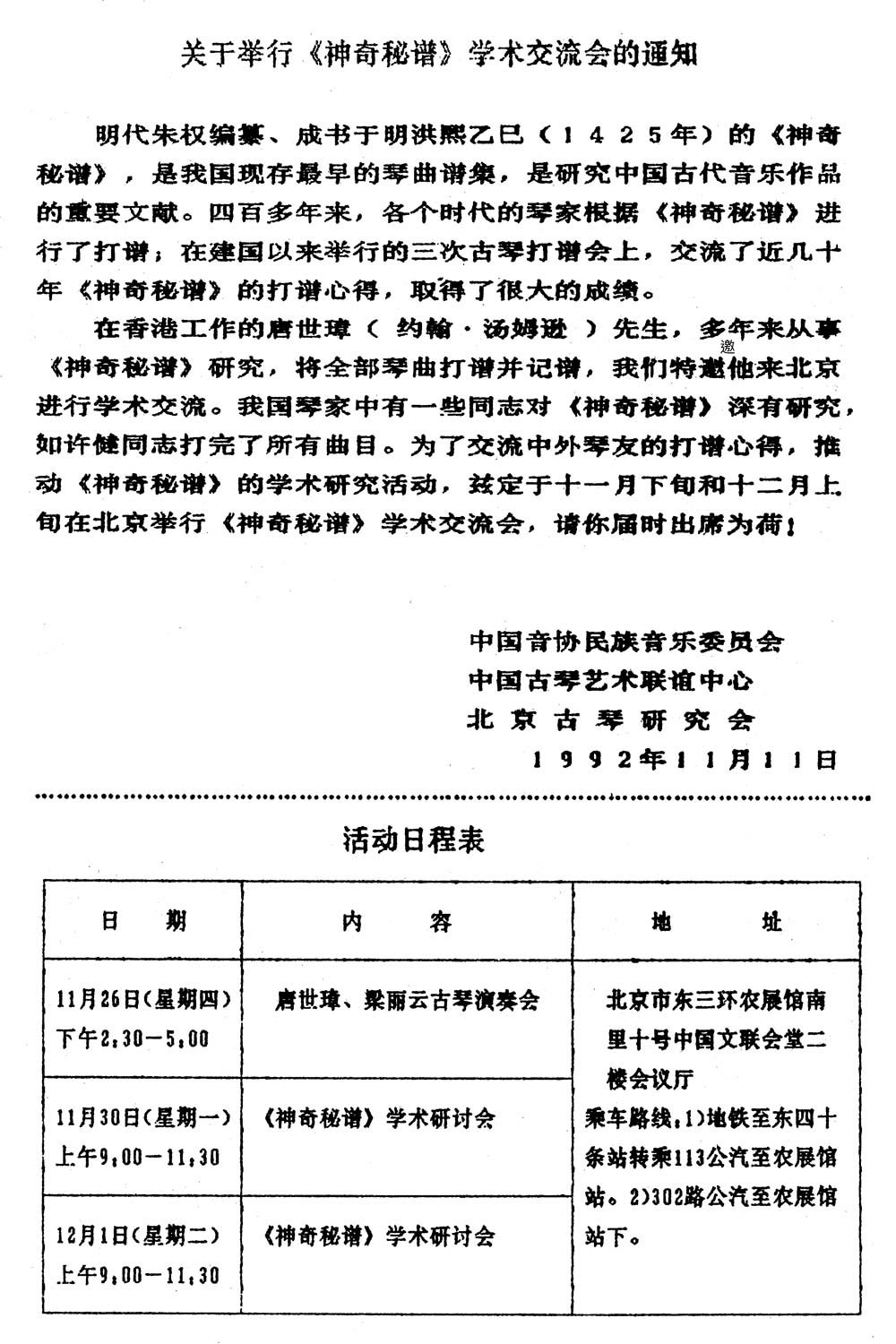

| 2. 《神奇秘譜》學術交流會 Shen Qi Mi Pu Academic Seminar, Beijing, November, 1992 | Seminar announcement (expand) |

This video shows me playing the Shen Qi Mi Pu melody Wild Geese in Autumn (Qiu Hong; 18.55) on another day of the seminar at the venue ahown above (the camera is moving for the first 15 seconds and there is a banging noise from about 15.15 to 16.30; there is more video from that day, but it is in even worse condition).

This video shows me playing the Shen Qi Mi Pu melody Wild Geese in Autumn (Qiu Hong; 18.55) on another day of the seminar at the venue ahown above (the camera is moving for the first 15 seconds and there is a banging noise from about 15.15 to 16.30; there is more video from that day, but it is in even worse condition).

At right is the official announcement for the seminar. It can be translated as follows:

The Shen Qi Mi Pu, edited by the Ming dynasty (prince) Zhu Quan and made into a book in 1425, is our country's earliest existing collection of qin melodies, and an important publication for studying China's ancient music pieces. For over 400 years qin masters of all periods have played melodies directly from the Shen Qi Mi Pu. At the three guqin melody reconstruction conferences carried out since the establishment of (the People's Republic in 1949?), we have gained decades of experience at reconstructing melodies from Shen Qi Mi Pu, achieving considerable results.

While working in Hong Kong Mr. Tang Shizhang (John Thompson) has engaged for many years in research into the Shen Qi Mi Pu, reconstructing all its melodies and writing out transcriptions, so we have especially invited him to come to Beijing for conducting an academic seminar. Our country's qin experts include a number of comrades who have done significant research into the Shen Qi Mi Pu; for example, comrade Xu Jian (author of the Introductory History of the Qin) has reconstructed all of (its?) melodies. In order to exchange music reconstruction experiences with a qin friend from outside China, we are promoting "Shen Qi Mi Pu" academic research activities, arranging during the last week of November and the first week of December for there to be a Shen Qi Mi Pu Academic Seminar. Please come and attend.

Schedule of events 活動日程表

Further notes on the announcement

After the event I was told there was a certain amount of controversy during deliberations about inviting a foreigner to be the focus of such an event.

3.

指法釋 Finger technique explanations

Return to the Shen Qi Mi Pu index

or to the Guqin ToC.

(Sponsors:)

(All are related to the 中國音樂家協會 National Union of Chinese Musicians.)

11 November 1992

[北京市東三環農產館南里十號中國文聯會堂二樓會議廳; directions are given.])

The Chinese term, "打譜 dapu", is relatively new and can also be translated as "reconstructed". The term is new and refers to learning from tablature rather than from a teacher. Often it just refers to playing freely based on the tablature; if done strictly, so as to try to re-capture the original way of its playing, it can be translated as "reconstructed".

In fact, Xu Jian (1923-2017) wrote out transcriptions of these and many other melodies, but he did not play them, so his reconstructions should be considered quite tentative. This is shown by the fact that in his very valuable and important work, Introductory History of the Qin, he analyzed many melodies, but he almost always used the modern versions of melodies, not the earlier ones closer to the periods to which he ascribed them.

(Return)

Although Shenqi Mipu itself did not have finger technique explanations, some modern edition added such explanations as compiled by

Yuan Quanyou: see her

Collected Notes on Finger Techniques

(指法集註 Zhifa Jizhu;

pdf.

(Return)