|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| TGYY ToC / Latter Red Cliff Rhapsody / Trace both / Battle of Red Cliff | 首頁 |

|

37. Former Red Cliff Rhapsody

- Standard tuning:2 5 6 1 2 3 5 6 played as 1 2 4 5 6 1 2 |

前赤壁賦

1

Qian Chibi Fu |

| Wu Yuanzhi: Red Cliff 3 |

The lyrics of the Former Red Cliff Rhapsody and Latter Red Cliff Rhapsody are personal accounts (in the form of fu: poetic essays/rhapsodies) by the famous poet Su Dongpo (1037 - 1101). During 1080-86 Su was in exile as a minor official at Huangzhou (main city Huanggang), on the Yangzi River in what is today Hubei province. While there he made trips with some friends to a nearby scenic river spot called Red Cliff.4 This was the place where, according to local tradition, the famous Battle of Red Cliff had taken place.5 This famous battle actually did occur over 800 years earlier, in 208/9, but its location is disputed.6 According to Su's narrative his own trips took place in the 7th and 10th lunar months of 1082. The two fu are thought to have been written shortly thereafter. The qualifiers "former" and "latter" were added later; some translations instead call them "first" and "second" rhapsodies (or "prose poems". In the first of the rhapsodies Su contrasts the fighting that took place there back then with the peacefulness of the present scene. This leads to comments about what can be possessed and what can not, as well as what is permanent and what is not.

The lyrics of the Former Red Cliff Rhapsody and Latter Red Cliff Rhapsody are personal accounts (in the form of fu: poetic essays/rhapsodies) by the famous poet Su Dongpo (1037 - 1101). During 1080-86 Su was in exile as a minor official at Huangzhou (main city Huanggang), on the Yangzi River in what is today Hubei province. While there he made trips with some friends to a nearby scenic river spot called Red Cliff.4 This was the place where, according to local tradition, the famous Battle of Red Cliff had taken place.5 This famous battle actually did occur over 800 years earlier, in 208/9, but its location is disputed.6 According to Su's narrative his own trips took place in the 7th and 10th lunar months of 1082. The two fu are thought to have been written shortly thereafter. The qualifiers "former" and "latter" were added later; some translations instead call them "first" and "second" rhapsodies (or "prose poems". In the first of the rhapsodies Su contrasts the fighting that took place there back then with the peacefulness of the present scene. This leads to comments about what can be possessed and what can not, as well as what is permanent and what is not.

These rhapsodies are the subject of a number art works, both painting and calligraphy.7 Four examples are discussed on these pages,

- 蘇東坡 Su Dongpo (1037 - 1101), his own calligraphy for the Former Red Cliff Rhapsody.

- 武元直 Wu Yuanzhi (late 12th c.), Former Red Cliff Rhapsody

National Palace Museum, Taiwan - 文徵明 Wen Zhengming (1470-1559),

Latter Red Cliff Rhapsody

National Palace Museum, Taiwan - 喬仲常 Qiao Zhongchang, Latter Red Cliff Rhapsody (ca. 1123 CE)

Nelson-Atkins Museum, Kansas City.8

National Palace Museum, Taiwan

As for settings of the lyrics for qin, they are all largely syllabic, following the common pairing method for almost all known qin songs. The present piece is a setting of the former fu; next (see next melody) is a setting of the latter one. These do not appear in the 1511 edition of Taigu Yiyin, but only its continuation, dated 1515.

Settings of the lyrics for the former fu survive in at least 11 later handbooks up to about 1802 (see chart); as for the latter fu, settings survive only in the first three of these 11 handbooks and then in an additional one dated 1828. It should be noted, though, that although the lyrics are all the same, the music all seems to be different.9

There have been a number of published translations of the poems into English.10 The translation here is largely indebted to these earlier ones, the emphasis here being on a word for word understanding to help someone trying to follow the lyrics while listening.

Original preface

11

According to Chao Buzhi's Preface to the Continuation of Li Sao,12 "the former and latter Red Cliff Rhapsodies were written by Master Su. (During a famous battle here in ancient times), Cao Cao with his world-conquering attitude floated large boats on the river, as far as the eyes could see there were no Wu (soldiers). Zhou Yu was a young man, Huang Gai his subordinate general, a torch was used to burn (Cao Cao's boats). (Centuries later) Master (Su), when demoted to a post at Huanggang, often traveled below Red Cliff, forgetting his worldy aims. Seeing the river waves rushing clean he naturally meditated on the past, and in accord with (Zhou) Yu's skills wrote this rhapsody, and so on.

Music and Lyrics: Ten sections

13

(followed by the Latter Red Cliff Rhapsody)

(Not divided in the 1511 tablature; divisions here generally follow

later versions, but these have inconsistencies)

-

壬戌之秋,七月既望,

Rén xū zhī qiū, qī yuè jì wàng,

In autumn of the renxu year, during the full moon of the 7th lunar month (12 August 1082 CE),

蘇子與客泛舟,遊於赤壁之下。

Sūzi yǔ kè fàn zhōu, yóu yú Chì bì zhī xià.

I with some guests (hereafter "friends") went floating on a boat, traveling below Red Cliff.

清風徐來,水波不興。

Qīng fēng xú lái, shuǐ bō bù xīng.

Fresh breezes calmly arrived, ripples on the water did not rise.

舉酒屬客,誦明月之詩,

Jǔ jiǔ shǔ kè, sòng míng yuè zhī shī,

As I raised my wine and poured it for my friends, I intoned the poem about a bright moon.14

歌窈窕之章。

Gē yǎo tiǎo zhī zhāng.

And sang phrases about its seductive beauty. -

少焉,月出於東山之上,

Shǎo yān, yuè chū yú dōng shān zhī shàng,

Soon, the moon appeared above the eastern mountains,

徘徊于鬥牛之間。

Pái huái yú dòu niú zhī jiān.

And hovered in the northern sky.15

白露橫江,水光接天。

Bái lù héng jiāng, shuǐ guāng jiē tiān.

White dew extended across the river, shimmering water met the sky.

縱一葦之所如,淩萬頃之茫然。

Zòng yī wěi zhī suǒ rú, líng wàn qǐng zhī máng rán.

We let our reed boat drift as it wished, and floated over a great expanse without limit,

浩浩乎,如馮虛禦風,

Hào hào hū, rú féng xū yù fēng,

And at will, as if traversing the void we rode the winds,

而不知其所止;

Ér bù zhī qí suǒ zhǐ;

Not knowing where we might stop;

飄飄乎,如遺世獨立,

Piāo piāo hū, rú yí shì dú lì,

We soared, as if in transcending the world we stood alone,

羽化而登仙。

Yǔ huà ér dēng xiān.

Sprouting wings as if we had become immortals.

於是飲酒樂甚,扣舷而歌之。

Yú shì yǐn jiǔ lè shén, kòu xián ér gē zhī.

Thus, as we drank our wine and enjoyed it greatly, I tapped on the side of the boat and sang out. -

歌曰:

Gē yuē:

The song went,

「桂棹兮蘭槳,

Guì zhào xī lán jiǎng,

Cassia oars, ah; a magnolia rudder;

擊空明兮泝溯流光。 ("泝" was here erroneously written "沂")

Jí kōng míng xī yí sù sù liú guāng.

Stroke the reflected light, ah; going upstream the (water) flows brightly.

渺渺兮於懷,

Miǎo miǎo xī yú huái,

She is so remote, ah; my cherished;

望美人兮天一方。」

Wàng měi rén xī tiān yī fāng.'

I look for my beautiful one, ah; in the vast heavens.'

客有吹洞蕭者,倚歌而和之,

Kè yǒu chuī dòng xiāo zhě, yǐ gē ér hé zhī,

My friends included a dongxiao flautist, and with song I accompanied him.

其聲嗚嗚然:

Qí shēng wū wū rán:

Its sound was like "wu wu",

如怨如慕,如泣如訴;

Rú yuàn rú mù, rú qì rú sù;

As if lamenting, as if yearning; as if sobbing, as if complaining.

餘音嫋嫋,不絕如縷;

Yú yīn niǎo niǎo, bù jué rú lǚ;

Other notes were graceful, not cut off but like a fine thread;

舞幽壑之潛蛟,

Wǔ yōu hè zhī qián jiāo,

(The sounds were of) dancing through the sunken depths of submerged dragons,

泣孤舟之嫠婦。

Qì gū zhōu zhī lí fù.

And the crying around the solitary boats by widowed women.

蘇子愀然,正襟危坐,

Sūzi qiǎo rán, zhèng jīn wēi zuò,

I myself became sorrowful. Adjusting my clothing I sat up straight,

而問客曰:「何爲其然也?」

Ér wèn kè yuē: `Hé wèi qí rán yě?'

And asked my friend, "Why are you acting this way?"

客曰:「"月明星稀,烏鵲南飛。"

Kè yuē: `"Yuè míngxīng xī, wū què nán fēi."

My friend said, "'The moon shines so stars are few, crows and magpies fly south.'

此非曹孟德之詩乎?

Cǐ fēi Cáo Mèngdé zhī shī hū?

Is this not (lines from) a poem by Cao Mengde?16

"西望夏口,東望武昌;

"Xī wàng Xiàkǒu, dōng wàng Wǔchāng;

"'Towards the west is Xiakou, towards the east is Wuchang;

山川相繆,鬱乎蒼蒼。"

Shān chuān xiāng móu, yù hū cāng cāng."

Mountains and rivers intertwine, the foliage is gloomy.'

此非孟德之困于周,郎者乎?

Cǐ fēi Mèngdé zhī kùn yú Zhōu láng zhě hū?

Is this not where Mengde had been surrounded by the young Zhou (Yu)?- (泛音 harmonics)

方其破荊州,下江陵,

Fāng qí pò Jīngzhōu, xià Jiānglíng,

Having smashed Jingzhou and descended on Jiangling,

順流而東也,

Shùn liú ér dōng yě,

(Cao Cao) had followed the currents eastward,

舳艫千里, 旌旗蔽空。

Zhú lú qiān lǐ, jīng qí bì kōng.

Ships stem to stern for 1000 li, flags obscuring the sky.

釃酒臨江,橫槊賦詩。

Shāi jiǔ Línjiāng, Héng shuò fù shī.

He poured himself wine at the river's edge, set down his lance and wrote (this) poem.

固一世之雄也,而今安在哉?

Gù yī shì zhī xióng yě, ér jīn ān zài zāi?

He was certainly the hero of his age, but now where is he?- (harmonics)

況吾與子?

Kuàng wú yǔ zi?

How is it, then, with you and me?

漁樵于江渚之上,侶魚蝦而友麋鹿。

Yú qiáo yú jiāng zhǔ zhī shàng, lǚ yú xiā ér yǒu mí lù.

A fisherman and woodcutter on an islet in the river, companions to fish and friends of deer.

駕一葉之扁舟,舉匏樽以相属。

Jià yīyè zhī piān zhōu, jǔ páo zūn yǐ xiāng zhǔ.

We ride in a solitary small boat, and raise our wine gourds to toast each other.

寄蜉蝣與天地,渺滄海之一粟。

Jì fú yóu yǔ tiān dì, miǎo cāng hǎi zhī yī sù.

We lodge on earth as briefly as mayflies, insignificant grains in a vast ocean.

哀吾生之須臾,羨長江之無窮。

Āi wú shēng zhī xū yú, xiàn Chángjiāng zhī wú qióng;

We mourn our lives must be so short, and envy the Great River's limitless expanse.

挾飛仙以遨遊,抱明月而長終。

Xié fēi xiān yǐ áo yóu, bào míng yuè ér zhǎng zhōng;

We believe in flying immortals and roaming with them, embracing bright moonlight forever.

知不可乎驟得,托遺響於悲風。」

Zhī bù kě hū zhòu dé, tuō yí xiǎng yú bēi fēng.'

Knowing that these cannot suddenly be attained, I entrust these bequeathed sounds to the melancholy breezes."- 蘇子曰:

Sūzǐ yuē:

I myself then said,

「客亦知夫,水與月乎? corrected from "客亦知夫,"

`Kè yì zhī fū, shuǐ yǔ yuè hū?

"Do you my friend really understand it, water and moonlight?

逝者如斯,而未嘗往也;

Shì zhě rú sī, ér wèi cháng wǎng yě;

The one passes by here, but has never gone away;

盈虛者如彼,而卒莫消長也。

Yíng xū zhě rú bǐ, ér zú mò xiāo zhǎng yě.

The other can be empty or full, but in the end it never changes size.

蓋將自其變者而觀之,

Gài jiāng zì qí biàn zhě, ér guān zhī,

(So) taking this from the standpoint of change and looking at it,

而天地曾不能一瞬;

Ér tiān dì céng bù néng yī shùn;

then heaven and earth cannot remain the same for even an instant.

自其不變者而觀之,

Zì qí bù biàn zhě ér guān zhī,

(But) taking this from the standpoint of not changing and looking at it,

則物於我皆無盡也。

Zé wù yú wǒ jiē wújìn yě.

then external objects and the self both have no limit.

而又何羨乎?

Ér yòu hé xiàn hū?

So what reason is there for envy?- 且夫天地之間,物各有主。

Qiě fū tiān dì zhī jiān, wù gè yǒu zhǔ.

Furthermore, within heaven and earth, every object has its master.

苟非吾之所有,雖一毫而莫取。

Gǒu fēi wú zhī suǒ yǒu, suī yī háo ér mò qǔ.

If something is not mine, then I cannot fully obtain even the tiniest hair of it.

惟江上之清風,與山間之明月,

Wéi jiāng shàng zhī qīng fēng, yǔ shān jiān zhī míng yuè,

But as for a clear breeze over the river, along with moonlight shining in the mountains,

耳得之而爲聲,目遇之而成色。

Ér dé zhī ér wèi shēng, mù yù zhī ér chéng sè.

if the ears catch one it has sound, and if the eye experiences the other it has color.

取之無禁,用之不竭。

Qǔ zhī wú jìn, yòng zhī bù jié.

These can be taken without limit, and used without ever using them up.

是造物者之無盡藏也,而吾與子之所共適。」

Shì zào wù zhě zhī wú jìn cáng yě, ér wú yǔ zǐ zhī suǒ gòng shì.'

Such is Creation's limitless storehouse, and for me and you they are freely available.- (harmonics)

客喜而笑,洗盞更酌,

Kè xǐ ér xiào, xǐ zhǎn gēng zhuó,

My friends were happy and laughed. We washed our cups and poured more wine.

肴核既盡,杯盤狼藉。

Yáo hé jì jǐn, bēi pán láng jí.

The food and snacks finished, the cups and plates looked like wolves had gone through them.

相與枕藉乎舟中,

Xiāng yǔ zhèn jí hū zhōu zhōng,

We then leaned against each haphazardly in the boat,

不知東方之既白。

Bù zhī dōng fāng zhī jì bái.

Unaware that in the east daylight was arriving.

The translation above is largely indebted to these earlier ones, the emphasis here being on a word for word understanding to help someone trying sing or even just follow the lyrics while listening.

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

| 1. Former Red Cliff Rhapsody (Qian Chibi Fu 前赤壁賦) | In Su Dongpo's own calligraphy (beginning; expand) |

Wiki has further details about the calligraphy at right, said to have been written by Su Dongpo himself. As can be seen, his own calligraphy does not break the poem into sections - or even any punctuation. If he wrote another version with punctuation there is no known record of it. Nor is there any evidence he ever set it for music.

Wiki has further details about the calligraphy at right, said to have been written by Su Dongpo himself. As can be seen, his own calligraphy does not break the poem into sections - or even any punctuation. If he wrote another version with punctuation there is no known record of it. Nor is there any evidence he ever set it for music.

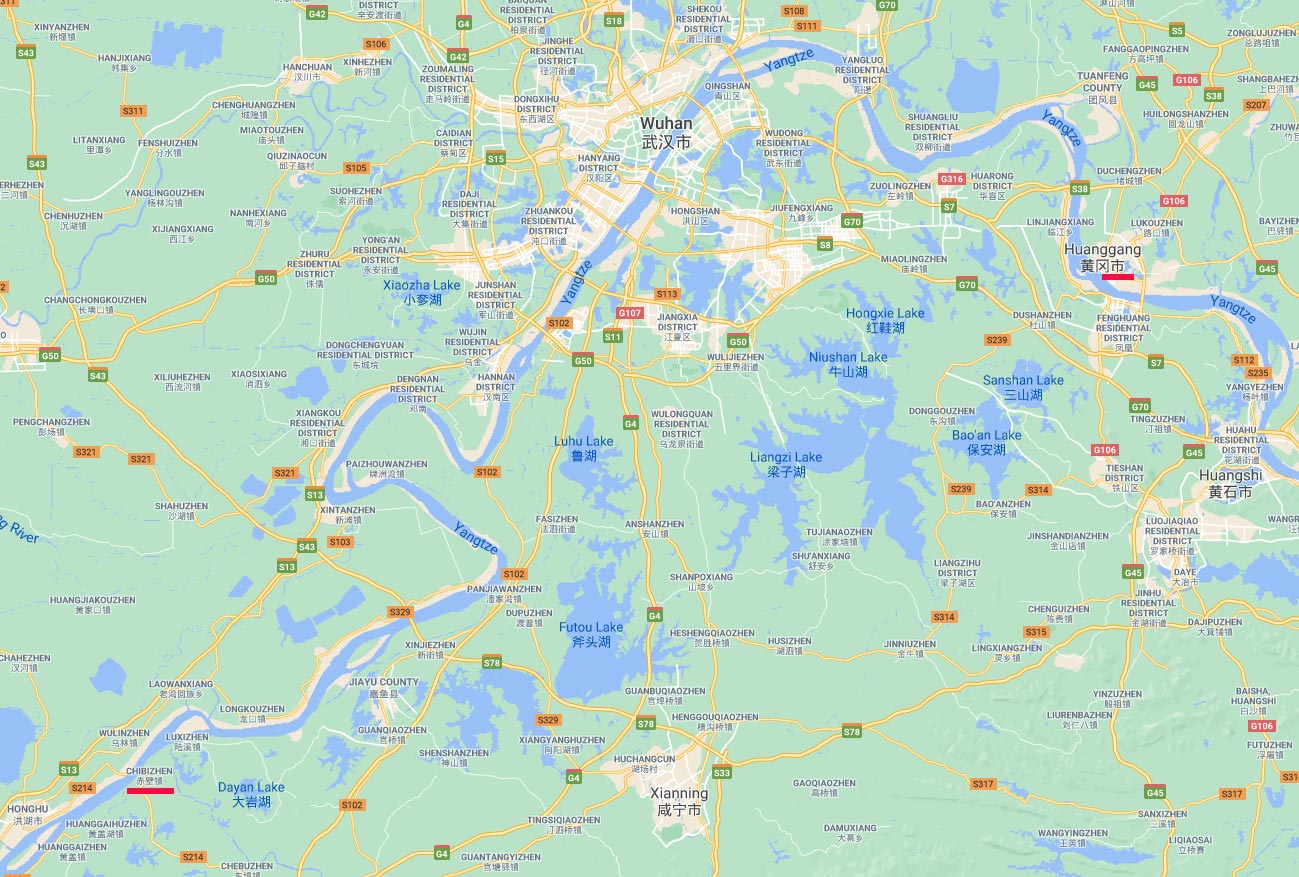

There are at least two Red Cliffs on the Yangzi river:

- In Hunan province up the Yangzi River from Wuhan

(further below)

Historians generally think this is where the famous battle actually took place. - In Hubei province down the Yangzi friver from Wuhan

(further below)

This is where Su Dongpo, most painters and many others seem to have preferred to imagine it took place, at least until recently.

Neither area has landscape as dramatic as that shown in paintings such as the one above. See further in the footnotes below.

(Return)

2.

Tuning and Mode

Taigu Yiyin does not organize melodies by mode. The version in 1539 is grouped under zhi mode, but it seems actually to be in huangzhong (raise fifth string, lower first). In 1585 it is in shang mode, with still other modes mentioned elsewhere.

(Return)

3.

Red Cliff Image by Wu Yuanzhi (武元直赤壁)

The original of this painting, in the collection of the National Palace Museum, Taiwan, is dated ca. 1100 CE. Wu Yuanzhi was a Jin dynasty scholar-official known to have been active 1190–96. I have a copy from the Museum shop.

(Return)

| Two Red Cliffs (Su Dongpo's is at upper right) |

4. Location of Su Dongpo's Red Cliff

4. Location of Su Dongpo's Red Cliff

The Red Cliff mentioned by Su Dongpo was down the Yangzi river from Wuhan, near what is today 黃岡 Huanggang (in 黃州 Huangzhou); from 1069 to 1074 Su was posted here as an official. This Red Cliff is also the subject of another poem by Su Dongpo, 赤壁懷古 Chibi Huaigu (see online translation). Apparently the historical characters for this Chibi are 赤鼻, not 赤壁, and it is on the north bank rather than the south, the latter being considered correct. In addition, photographs of this site show a gap between the images by painters and the geographical reality here. See, for example, the images now on the 華夏 Huaxia web pages dated 2005 and 2007 (translation). Nevertheless, claims for this place persist. See also the next footnote below.

(Return)

5.

Location of Red Cliff battle

There is considerable argument about the actual location of this battle. The site most commonly named by historians is up the Yangzi River from Wuhan about midway between Wuhan and Yueyang, near the Hunan/Hubei border. It is not far from a township formerly named 蒲圻 Puqi; in 1998 the name was offially changed to Red Cliff Town (赤壁鎮 Chibi Zhen) to bolster its claims, and a tourist site has been built here. Available online photographs of the cliff here may suggest that this location has more in common with the paintings than does Dongpo's Chibi (see previous footnote), but more panoramic photographs would also show the paintings to have been very fanciful. (See, for example, the first image on

this website;

translation.)

(Return)

6.

Red Cliff Battle

(Wikipedia)

The battle was fought during the winter of 208-9 (i.e., 874 years before 1082, when Su Dongpo is thought to have written Chibi Fu), shortly after the Viceroy of Wu 周瑜 Zhou Yu (175-210) had married one of the daughters of Qiao Xuan

(Wiki). At the battle Zhou, with some assistance from the soon to be famous strategist Zhuge Liang of Shu, combined to stop an attack by Cao Cao of Wei. Most famously they used a ruse suggested by 黃蓋 Huang Gai: he would pretend to surrender, and sail several boats secretly filled with incendiary devices into Cao Cao's massed fleet, then set them ablaze. In the battle Zhou Yu was wounded by an arrow; he survived but his death the following year was apparently due to infection from the wound. There is quite a bit of information on the internet about this battle.

Red Cliff: the film score (and guqin "duet"; see also Qin in film)

The battle at Red Cliff was the focus of a 2008 film called Red Cliff (see, for example, Answers and Wikipedia; the original film is in two parts, each over 2 hours long, of which I have seen only the first). In the film, when

Zhou Yu and

Zhuge Liang together decide to oppose Cao Cao, they show their likemindedness by successfully playing a qin duet together. The music they play largely comes from repeating certain particularly flashy phrases from the melodies Guangling San and the modern Liu Shui apparently as played by 趙家珍 Zhao Jiazhen (at writing it can be seen here and elsewhere on YouTube). For this music the credits say only "中國古琴作曲唐建平 Chinese zither composer Tang Jianping", with no mention of the actual player, suggesting perhaps Tang recorded (or took existing recordings of) individual passages (on a single nylon/metal or composite string qin), then himself put the bits together electronically. The film also has a passage with eerie music played in Japanese noh flute style. Otherwise, although the film seems with its costumes and story to be trying to give a semblance of historical accuracy, the film score, by Taro Iwashiro, has virtually no Chinese flavor; even the qin is treated as though it would have been better off as a 19th century Western instrument. It is disconcerting to read some online comments on the score by people who clearly would find it odd if the characters wore Western clothing for a Chinese period movie, but seem to have no problem with the film's apparent allergy to Chinese music traditions.

(Return)

7.

Other famous Red Cliff paintings

For several examples in New York's Metropolitan Museum, including two from Japan, search the museum website for "red cliff". For the Latter Red Cliff Rhapsody see next footnote.

(Return)

8.

Nelson Atkins Scroll: 喬仲常 Qiao Zhongchang (n.d.), Latter Red Cliff Rhapsody (ca. 1123 CE)

This long scroll in the collection of the Nelson-Atkins Museum, Kansas City, specifically refers to the Latter Red Cliff Rhapsody, and so there is further discussion with this site's page about that melody.

(Return)

9.

Tracing various versions of Chibi Fu

(tracing chart)

The chart is based largely on three entries in Zha Guide, as indicated

below.

(Return)

10.

Translations of the Red Cliff Rhapsodies

There are many online translations, often not identifying the translator. Printed translations include:

- Red Cliff I and II, in Richard Strassberg, Inscribed landscapes: travel writing from imperial China, pp. 185-88

May be available online: search for "In the fall of the year jen" - Red Cliff Rhapsodies, 1 and 2; translated by Richard Strassberg (identical to previous)

Victor Mair, The Columbia Anthology of Traditional Chinese Literature; NY, Columbia U. Press, 1994l; pp. 438 - 440 - Two Prose Poems on the Red Cliff; translated by Burton Watson

Burton Watson, Selected Poems of Su Tung-p'o; Port Townsend, Copper Canyon Press, 1994; pp. 94 - 98 - The Poetic Exposition on Red Cliff; translated by Stephen Owen

Stephen Owen, An Anthology of Chinese Literature; New York, W.W. Norton, 1996; pp. 292 - 294 and (#2) 675 - 676 - First and Second Fu on the Ch'ih-pi (Red Cliff), translated by Liu Shih-Shun

Liu Shih-Shun, Chinese Classical Prose: The Eight Masters of the T'ang-Sung Period; Hong Kong, Chinese University Press, 1979. pp. 260 - 267. His translation of the former rhapsody (First Fu on the Ch'ih-pi (Red Cliff) was once available online together with with simplified Chinese, English and Vietnamese versions!

See also this translation of the former rhapsody accompanying a calligraphy scroll.

(Return)

11.

Original preface

The Chinese original is as follows:

(Return)

12.

晁補之 Chao Buzhi (1053-1110; Renditions; sometimes transliterated Zhao Buzhi)

14239.2 "宋鉅野人,字无咎...." Chao was a Song dynasty scholar-official from Juye (in Shandong), style name Wujiu. He was a friend and protégée of Su Dongpo. His writings included a 琴趣外篇 Qin Qu Waipian.

(Return)

13.

Original lyrics of Qian Chibi Fu (also see the accompanying melody

Hou Chibi Fu)

In Taigu Yiyin the Chinese lyrics, which pair Su Dongpo's original poem (including the introduction) to the qin tablature using the standard method, are not clearly divided into sections. However, later versions seem to suggest arranging them into varying numbers of sections. The following shows a 10 section division, as above, largely following the sectioning of 1585 and 1596):

-

壬戌之秋,七月既望,蘇子與客泛舟遊於赤壁之下。清風徐來,水波不興。舉酒屬客,誦明月之詩,歌窈窕之章。

- 少焉,月出於東山之上, 徘徊于鬥牛之間。 白露橫江, 水光接天。 縱一葦之所如, 淩萬頃之茫然。 浩浩乎如馮虛禦風, 而不知其所止; 飄飄乎如遺世獨立, 羽化而登仙。 於是飲酒樂甚, 扣舷而歌之。

- 歌曰: 「桂棹兮蘭槳, 擊空明兮泝溯流光。 渺渺兮於懷, 望美人兮天一方。」

- 客有吹洞蕭者, 倚歌而和之, 其聲嗚嗚然: 如怨如慕, 如泣如訴; 餘音嫋嫋, 不絕如縷; 舞幽壑之潛蛟, 泣孤舟之嫠婦。

- 蘇子愀然, 正襟危坐, 而問客曰: 「何爲其然也?」 客曰: 「"月明星稀,烏鵲南飛。" 此非曹孟德之詩乎? "西望夏口, 東望武昌; 山川相繆, 鬱乎蒼蒼。" 此非孟德之困于周郎者乎?

- 方其破荊州, 下江陵, 順流而東也, 舳艫千里, 旌旗蔽空。 釃酒臨江, 橫槊賦詩。 固一世之雄也, 而今安在哉?

- 況吾與子, 漁樵于江渚之上, 侶魚蝦而友麋鹿, 駕一葉之扁舟, 舉匏樽以相属; 寄蜉蝣與天地, 渺滄海之一粟。 哀吾生之須臾, 羨長江之無窮; 挾飛仙以遨遊, 抱明月而長終; 知不可乎驟得, 托遺響於悲風。」

- 蘇子曰: 「客亦知夫水與月乎? 逝者如斯, 而未嘗往也; 盈虛者如彼, 而卒莫消長也。 蓋將自其變者而觀之, 而天地曾不能一瞬; 自其不變者而觀之, 則物於我皆無盡也。 而又何羨乎?

- 且夫天地之間, 物各有主。 苟非吾之所有, 雖一毫而莫取。 惟江上之清風, 與山間之明月, 耳得之而爲聲, 目遇之而成色。 取之無禁, 用之不竭。 是造物者之無盡藏也, 而吾與子之所共適。」

- 客喜而笑, 洗盞更酌, 肴核既盡, 杯盤狼藉。 相與枕藉乎舟中, 不知東方之既白。

- 少焉,月出於東山之上, 徘徊于鬥牛之間。 白露橫江, 水光接天。 縱一葦之所如, 淩萬頃之茫然。 浩浩乎如馮虛禦風, 而不知其所止; 飄飄乎如遺世獨立, 羽化而登仙。 於是飲酒樂甚, 扣舷而歌之。

See also the translation.

(Return)

14.

Poem about a bright moon

The phrase here, 「誦明月之詩, 歌窈窕之章。」 is generally said to be a reference to Shi Jing poem #143 陳風 Airs of Chen, The Moon Emerges, the first verse of which is:

The poem compares the beauty of the moon to that of a young lady. However, it uses neither the full expression 月明 nor 窈窕.

(Return)

15.

The northern sky

The phrase here, 「鬥、牛之間。 Between the bean and the ox」, names stars or constellations roughly corresponding to the Big Dipper and Capricorn, both in the north.

(Return)

16.

A poem by Cao Mengde

Cao Mengde is 曹操 Cao Cao, 155 - 220). These lines can be found in the first of two ballads called 短歌行 Duan Ge Xing he is said to have written after the Red Cliff battle; the following lines seem to be from another poem, but their source has not been identified.

(Return)

Return to top

Appendix:

There is further comment above. Here the chart is based mainly on the first two of the three related entries in

Guide:

The comments about relationships between the melodies are tentative based on brief examinations; note also that pieces with different tunings sometimes are still related melodically.

Chart Tracing 前、後赤壁賦 Qian and Hou Chibi Fu

前赤壁賦 Qian Chibi Fu

14/152/283

後赤壁賦 Hou Chibi Fu

14/153/285

赤壁賦 Chibi Fu

28/--/--

The third of these does not list any not already listed in the first two.

|

琴譜

(year; QQJC Vol/page) |

Further information

(QQJC = 琴曲集成 Qinqu Jicheng; QF = 琴府 Qin Fu) |

|

1a. 黃士達太古遺音

(1515; I/328) |

1; Qian Chibi Fu (details); not in

1511

Standard tuning but no mode name given |

|

1b. 黃士達太古遺音

(1515; I/330) |

1; Hou Chibi Fu (further); not in 1511

Standard tuning but no mode name given |

|

2a. 風宣玄品

(1539; II/265) |

1; Qian Chibi Fu; same lyrics but different music from 1511;

Grouped with zhi mode but tuning seems to be huangzhong, as in 1589 |

|

2b. 風宣玄品

(1539; II/269) |

1; Hou Chibi Fu; same lyrics but different music from 1511;

Grouped with zhi mode but tuning seems to be huangzhong (not in 1589) |

|

3a. 重修真傳琴譜

(1585; IV/372) |

8T; Qian Chibi Fu; grouped with shang mode

Same lyrics, different music from previous |

|

3b. 重修真傳琴譜

(1585; IV/374) |

6T; Hou Chibi Fu; grouped with shang mode

Same lyrics, different music from previous |

|

4. 玉梧琴譜

(1589; VI/83) |

7; "Chibi Fu", only Former; ruibin mode;

Another new melody |

|

5.

真傳正宗琴譜

(1589; VII/130) |

11T; Qian Chibi Fu; Huangzhong mode (1 3 5 6 1 2 3); no Hou Chibi Fu

Almost same as 1539 (散抹六,勾五,跳七,大九勾四....") but divides into sections |

|

. 真傳正宗琴譜

(1609; Fac/) |

Should be same as 1589

|

|

6. 文會堂琴譜

(1596; VI/210) |

10; Qian Chibi Fu; grouped with shang mode

|

|

7. 藏春塢琴譜

(1602; VI/425) |

7; "Chibi Fu" but only Former; ruibin: copy of 1589

|

|

8. 陽春堂琴譜

(1611; VII/--) |

11TL; Qian Chibi Fu; Raise 5th, lower 1st tuning;

missing;

Compare 1589 (lyrics same; adds section titles) (太古正音欽佩) |

|

9.

理性元雅

(1618; VIII/261) |

11; Qian Chibi Fu; Huangzhong; related to

1589

|

|

10. 自遠堂琴譜

(1802; XVII/538) |

8; Qian Chibi Fu; zhi diao gong yin but raise 5th, lower 1st;

Related to 1589 |

|

11. 裛露軒琴譜

(>1802; XIX/119) |

11T; Qian Chibi Fu; Huangzhong;

"1589", but without the lyrics |

|

12. 琴學軔端

(1828; XX/437) |

5, unnumbered; Hou Chibi Fu; huangzhong mode; difficult to read;

section 1-4 breaks as 1585 but different music; Seems to start, "泛起,大七勾三,勾四,抹跳五,中七勾一,大七托五...." |