|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Qin Bios | 首頁 |

|

The Two Lius (Er Liu: Liu Shilong and Liu Yun)

- Qin Shi #104 |

二柳 (柳世隆、柳惲)1

琴史 #104 2 |

Although its title is the Two Lius, referring to Liu Shilong3 (442 - 491) and his younger son Liu Yun4 (465 - 517), this entry also mentions Liu Shilong's elder son Liu Yan5 (462 - 507). All were leading qin players in Jiankang (Nanjing), capital city of the 劉宋 Liu Song (420-479), 南齊 Southern Qi (479-502) and 梁 Liang (502-557) dynasties. Another son, Liu Yue,6 is not mentioned.

Liu Shilong (442 - 491) was a son of Liu Yuanjing7 (406 - 465), a high military official under the Liu Song emperor Xiao Wudi (r. 454 - 465). Liu Shilong has been connected to a qin melody called Autumn Evening Moon Walk.8

Liu Yan (462 - 507), the elder son of Liu Shilong, gets only a brief mention in the Qin Shi essay.

Liu Yun (465 - 517) is also discussed by Xu Jian in QSCB,

Chapter 4A (p.41). Apparently Liu Yun did not study from his father. The people connected to him in this biography include Ji Yuanrong,9 and

Yang Gai10, as well as

Dai Andao (Dai Kui, d. 395 CE) and

Prince Jingling of Qi (Xiao Ziliang11). However, there seems to be no mentione of another contemporary with importance for the qin:

Xiao Luan (452-498), who reigned 494-498 as Emperor Ming of Qi.

The original essay in Qin Shi is as follows:

Liu Yan (462 - 507), first son of Liu Shilong, was also skilled in musical tones.

Liu Yun (465 - 517), style name 文暢 Wenchang, was Liu Yan's younger brother. He wrote several poems including ones with the phrases:

and

Poets up to the present time (11th c.?) still praise (Liu Yun). He died as 吳興太守 Prefect of Wuxing (district south of 太湖 Taihu).

The early (Liu) Song dynasty still had (the teachings of) 嵇元榮 Ji Yuanrong and 羊蓋 Yang Gai, both good at qin. It was said that they carried on the methods of (Dai) Andao. Liu Yun when young studied them until he completely learned their techniques. Prince Jingling of Qi when once serving wine in his inner court had the unadorned qin of Jin minister 謝安 Xie An at his side. He gave it to Liu Yun to play an elegant melody, saying, "The fortunate minister's skills are better than those of Xi Kang, the emotions are as good as those of Yang (Gai). Good materials and good skills are all present. How wonderful not just for the present but also in terms of the skills of the ancients.

(Liu) Yun had a refined sense of musical tones but was especially devoted to qin. (There follows more discussion of his qin play, including saying that his essays 清調論 and 樂義 were well written and playing his father's melodies made him nostalgic so he adapted some for modern tastes. He composed many fu and shi poems but did not consider them adequate and so did not write them down. However, while playing songs he would hit the qin with his brush and guests seated around would use sticks to accompany him. Liu Yun was startled by the mournful sound and made this into an elegant sound. The later custom of "percussion qin" began with this.12 He was also especially good at 奕棋 playing wei qi chess. 梁武帝 Liang Wudi (502 - 550) said Liu Yun's skills were sufficient for 10 people.

See Luca Pisano for a complete translation.

1.

二柳 Er Liu (柳世隆、柳惲 Liu Shilong and Liu Yun)

No source is mentioned, but one is quite likely 陳氏,樂書, i.e., 陳暘,樂書 the Music Book by Chen Yang (11th-12th c.).

Details about Liu Shilong and his children can also be found in Andrew Chittick, Patronage and Community in Medieval China: The Xiangyang Garrison, 400-600 CE (SUNY Series in Chinese Philosophy and Culture, 2010).

On pp. 68-9 Chittick tells of another person of that time, 辛宣仲 Xin Xuanzhong, who played the 箏 zheng with the reclusive attitudes elsewhere usually ascribed to qin players. Unlike with qin players, though, Xin liked to play together with two friends, one of whom played flute, the other sang (the original text says "辛宣仲,善彈箏;胡陶,善吹龍笛;駱惠度,善歌唱。人稱之為「三公樂」。")

2.

17 lines; see Luca Pisano for a complete translation.

3.

柳世隆 Liu Shilong (442 - 491)

The source of the stories here connecting him to qin are not stated. See also Qiuxiao Bu Yue

4.

柳惔 Liu Yan

5.

柳惲 Liu Yun (465 - 517)

6.

柳悅 Liu Yue

7.

柳元景 Liu Yuanjing, a high military official under the Liu Song emperor 孝武帝 Xiao Wudi (r. 454 - 465)

(Return)

8.

Autumn Night Moon Walk

(秋宵步月 Qiuxiao Bu Yue) (QQJC III/268)

9.

Ji Yuanrong 嵇元榮

10.

Yang Gai 羊蓋 Bio.xxx

(Return)

11.

Xiao Ziliang, Prince Jingling of Qi 齊竟陵王蕭子良

12. 擊琴 Ji qin: "struck qin" or "hitting/striking a qin?

On pavilions by the riverbank tree leaves fall; above Mount Long autumn clouds fly.

翠華承漢遠,雕輦逐風遊。

In Taiye (pond) blue waves arise, at Changyang (Palace) tall trees (proclaim) autumn,

Emerald splendor inherited from distant Han, while ornate carriages chase the wind."

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

Since the essay also mentions 柳惔 Liu Yan as a good qin player, it is not clear why the essay is not called "The Three Lius".

(Return)

(Return)

15002.38 makes no mention of his musical activities; his dates are about a decade later than those of Xiao Luan (452-498). Originally from 襄陽 Xiangyang, Liu was a man of the 南齊 Southern Qi (479-501), 柳元景兄子 the son of an elder brother of Liu Yuanjing; style name 彥緒 Yanxu. He grew up in the Liu Song capital, Jiankang (Nanjing), then went back to the Xiangyang region as a military officer. His children, however, stayed in Nanjing. Details are in Chittick. A great-granddaughter became Empress Liu of the Chen Dynasty Wiki.

(Return)

15002.129 梁人,世龍之子,字文通,好學工文,尤曉音律,與兄悅齊名,王儉稱為柳氏二龍.... A man of the Liang dynasty (502-556). A son of Liu Shilong, style name Wentong, he enjoyed studying and was skilled at writing (?), being especially knowledgeable about music. He and his older brother Liu Yue were well-known in Qi, to the extent that Wang Jian (452-489; Wiki) called them The Two Dragons....

(Return)

15002.155; style name 文暢 Wenchang; entry says that at first his father Shilong was considered the best qin player around, but after Shilong died, "惲每奏其夫曲,常感思,復變體,備寫古曲,已復製為雅音 Liu Yun would repeatedly play his father’s pieces. Constantly moved by remembrance, he would further transform their forms, fully set down the ancient melodies, and then recreate them as refined music." Comments in Xu Jian, QSCB, Chapter 4A (p.41) do not mention some of the details here (see, e.g., hitting qin below).

(Return)

15002.115

(Return)

Further information here (see also Rao).

(Return)

Bio.xxx; 1356.xxx; a descendant of Xi Kang?

(Return)

蕭子良 Xiao Ziliang (32667.8). See story above.

(Return)

13075.45 擊琴 ji qin says only that it means either .1 彈琴 play qin or .2 樂曲名,唐柳惲作 name of a melody created by Liu Yun of the Tang dynasty. However, the references given for the latter, like here, seem to suggest that Liu Yun hit the qin with a bamboo stick. Meanwhile, although "擊琴 ji qin"" seems here actually to be the name of an instrument ("percussion qin"?), descriptions also seem focused on how a qin was played with sticks rather than saying it was an instrument of a specific shape or style.

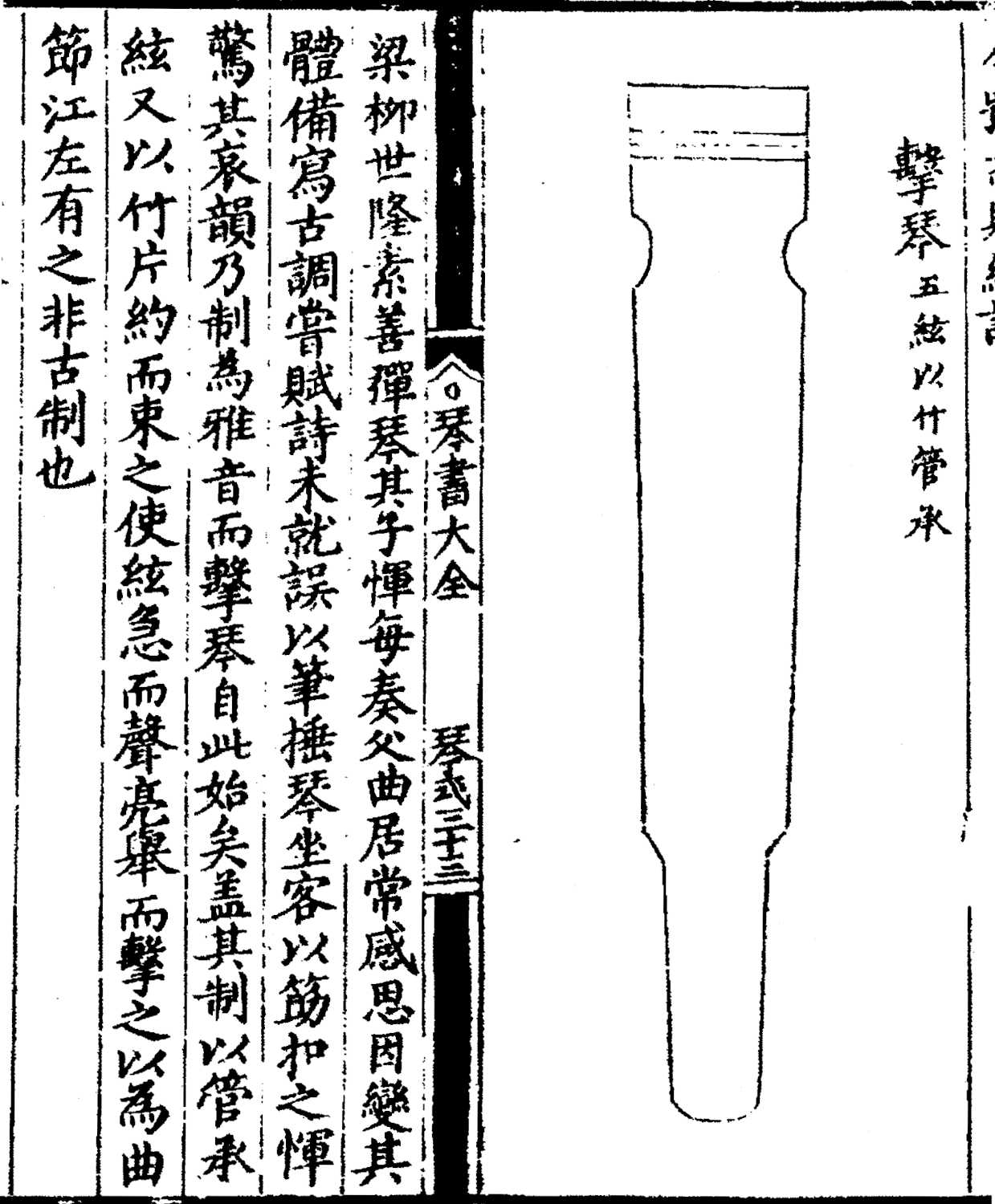

| Below right are two images for "擊琴 Ji qin": | "Hitting qin": Qinqu Jicheng |

Qinshu Daquan Chapter 5 (QQJC V/120) includes a qin shape it connects to Liu Shilong and Liu Yun. Called "擊琴(五絃,以竹管承)Struck qin (five strings, using bamboo and tubes)", it says this next to the image,

Qinshu Daquan Chapter 5 (QQJC V/120) includes a qin shape it connects to Liu Shilong and Liu Yun. Called "擊琴(五絃,以竹管承)Struck qin (five strings, using bamboo and tubes)", it says this next to the image,

Liu Shilong of Liang was always skilled at playing qin. His son Liu Yun, whenever he played his father's tunes, would likely be deeply moved by lingering emotions; as this led to modifications in its form, he thoroughly wrote down the old melody. Once, while composing a poem but not yet finished, he mistakenly tapped the qin strings with his calligraphy brush. A guest seated nearby then used a chopstick to make his own knocking sounds. (Liu Yun), struck by the mournful beauty of these sounds, then created elegant music, and from this (the custom of) "hitting the qin" began.

蓋其制以管承絃,又以竹片約而束之,使絃急而聲亮,舉而擊之,一為曲節。江左有之,非古制也。

The construction involved tensioning the strings over a tube (管承弦), and also binding this tightly with a bamboo slip (竹片约而束之), making the strings taut and the sound bright. Lifting [the slip] and striking [the strings] produced distinct musical segments (曲节: could this be not just rhythm but meter?). This (instrumental style) came to exist exist in the Jiangdong region (southeast China), but it is not an ancient form.

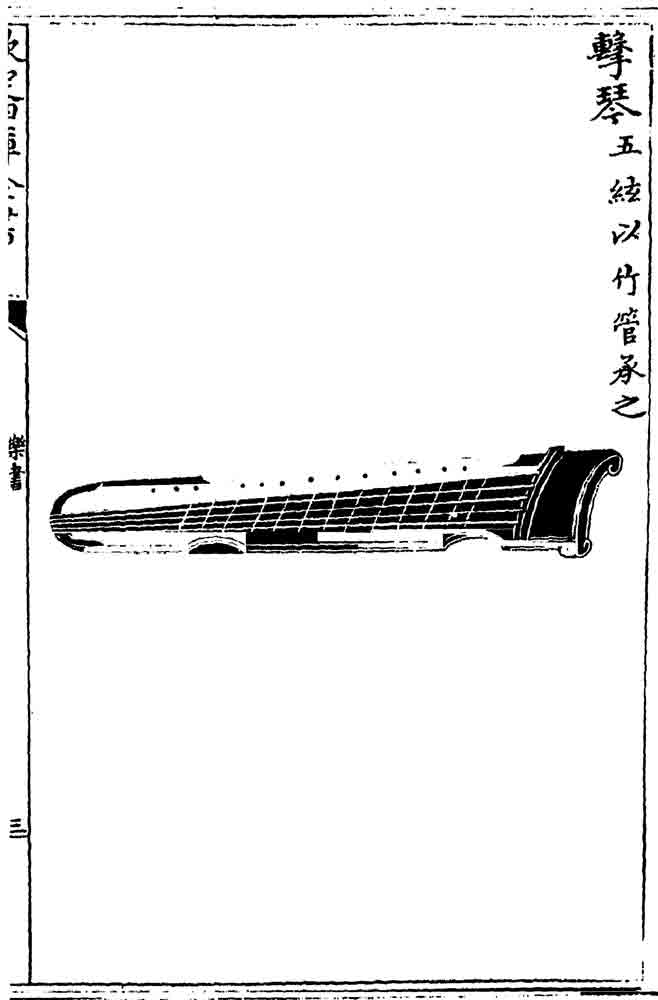

| "Hitting qin": Yue Shu |

Meanwhile, the image at right (expand), from the 樂書 Yue Shu of Chen Yang, has the same comment as above about "five strings, using bamboo and tubes to cheng it" and, on the facing page, the

same text as above. However, the image itself is rather different. Although it has more detail, as above I still do not know the meaning here of ""cheng"": receive? support? contain? etc.

Meanwhile, the image at right (expand), from the 樂書 Yue Shu of Chen Yang, has the same comment as above about "five strings, using bamboo and tubes to cheng it" and, on the facing page, the

same text as above. However, the image itself is rather different. Although it has more detail, as above I still do not know the meaning here of ""cheng"": receive? support? contain? etc.

Furthermore this second image is itself somewhat confusing as it is not clear to me the significance of the 13 lines, which are not quite lined up with the 13 harmonic markers (hui): whether lined up with the hui or not, frets seem unlikely, since having 13 of them would be unlikely to allow them to correspond with the positions of stopped sounds. Could they represent lines drawn on the instrument to help players know where to put their fingers? (See further comment on source of the image, as well as on the various types of "qin" described by Chen Yang. And see under origins for comment on the possibility of there having been other varieties.)

For a different example of percussion with qin see Zhang Dai.

(Return)