|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Accompanying CD Deng Hong CD | 首頁 |

|

Cecilia Lindquist:1

Qin2

A translation from Swedish of the Table of Contents and Preface 3 |

林西莉﹕琴

古琴的故事4 |

| The cover illustration is from a famous painting |

|

(Cover text:) Albert Bonniers Förlag (Published Stockholm, 2006) The story of the Chinese instrument called qin, and its significance within the lives of the educated classes, the music, poets, individuals and perceptions associated with the qin – not least how to live your life – and something of what I experienced when I became deeply involved in this. |

|

|

Foreword 8 |

pp. 30-31: Studying with Wang Di; Guan Pinghu

|

|

|

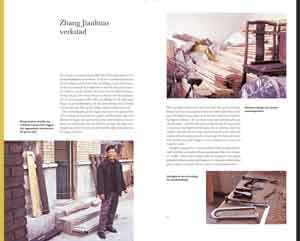

pp. 60-61: Workshop of 張建華 Zhang Jianhua

|

|

|

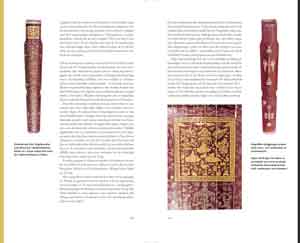

pp. 140-141: Ancient qins at Japan's Shoso-in

|

|

The Dream of Paradise 147

|

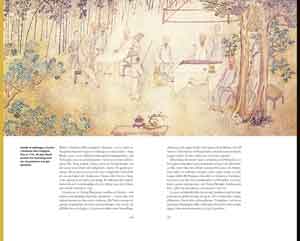

pp. 190-191: Qin in the Ma family garden, 1743

|

|

The qin symbol 254 Literature 259

|

pp. 230-231: (Left) Finger technique explanations (Right) An image from 1539

|

In the early spring of 1961 I saw a Chinese qin at close quarters for the first time. It was lying in front of me on a wooden table in a bare classroom at the University of Peking. Seven strings of tightly twisted silk stretched over a sound box made of black lacquered wood. After a certain amount of difficulty I had managed to get hold of a Chinese student who had promised to try to teach me the basics of playing the qin, and we were due to have our first lesson. He had brought his instrument with him. It dated from the Ming dynasty (1368-1644), and had been passed down through his family since that time.

When I touched one of the strings, the tone that was released made the whole room vibrate. It was as clear as silver, but remarkably it also had a kind of metallic dullness, as if the instrument were made not of wood, but of bronze. During the years which followed it was precisely the tone of the instrument that captivated me the most, from the finest bell-like tones or fanyin, "the floating sounds" as they are called in Chinese – delicate as the sound of the tiny temple bells right on the edge of the roof timbers when the wind gently stirs them – to the vibrating depths of the thick bass strings.

The melodies I later tried to learn were ancient and almost always consisted of a series of individual tones, no rich chords such as you find in European piano music, just individual tones, sometimes in octaves produced simultaneously on two different strings, where the different frequencies made the sound float and shimmer.

For more than two thousand years, the qin was the principal instrument of the educated classes. Many of the most dedicated players were philosophers and monks, and for them the instrument was a means to achieving self-realisation. Playing the qin was a kind of meditation, a way to free themselves from the world and to find a way to wisdom. But the qin also offered a refuge to tired officials, exiled opponents of the system, and poor poets, enabling them to escape from a harsh world and showing them the way to peace and the heart of Chinese culture.

The instrument has been surrounded by such a deep reverence that we have no equivalent in the West, and it is sung about in countless poems. Many gripping tales of various qin players and their fates are still extant and are constantly quoted, and many instruments well over a thousand years old are still in full use. It is a living and remarkably long tradition.

Over time the playing of the qin became ritualised and surrounded by a rich flora of stipulations, which regulated when and how one ought to play or absolutely must not play, how one should be dressed, how one should sit and what the room where one was playing should look like. It wasn’t just a case of dashing in from the kitchen and knocking out a quick tune while the rice was cooking. Playing required preparation, both mental and practical – it was in many ways a sacred activity. During recent decades this ceremonial behaviour has of course been scaled down somewhat, but the instrument is still perceived as a unique object and is preserved within families as a relic, even if no one plays it today. But new generations will come. Be sure of that.

The instrument is difficult to play. Everything is about the beauty of the individual tones and how the player produces them, tone after tone. There are 26 different kinds of vibrato and a further 54 clearly differentiated holds - nothing is left to chance.

One problem for beginners is that the music is not written in notes of the kind we are used to. Instead, a "note" is written as a combination of different signs and symbols that indicate on which string and where on that string the tone is to be produced, with which finger and which position. Another difficulty is that the notes give no detailed information on rhythm or phrasing, nor do they indicate how to move on to the next tone. Without a good and patient teacher, who can give step by step instructions, it is impossible to succeed.

Just as is the case with other highly specialised musical instruments, playing the qin demands a lifelong commitment from its exponents if they are to achieve a good result, and there are few who can meet such a demand. But if you approach the music of the qin in a very simple way, you will meet not only a unique and captivating music, you will also come close to the whole of ancient classical Chinese culture.

Many of the basic rules governing people’s lives and conduct, as they are formulated within the Confucian and Taoist traditions, pervade the ideology surrounding the playing of the qin. And every individual piece of music is charged with associations with nature – the orchid, the blossoming apricot tree, the tall mountains and the swirling waters of the streams, the crane, the skein of wild geese against the sky – motifs which also recur in countless poems and paintings throughout China’s long history.

|

CD included with the book 10 tracks are historical recordings of

Guan Pinghu (1897-1967) with silk strings;

|

Inside back cover:

|

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

1.

Cecilia Lindquist (in Swedish

Cecilia Lindqvist; in Chinese 林西莉)

Cecilia Lindquist is a Swedish scholar living in Stockholm. The original Swedish edition of her classic work on Chinese characters was awarded a prize as the best non-fiction book published in Sweden in 1989. The English edition, China: Empire of Living Symbols, is currently out of print, but is scheduled to be re-published soon. It has also been published in China (simplified characters), Taiwan (standard characters) and Korea. In Taiwan the Eslite book chain voted it the best book published there in 2006.

(Return)

| Covers of two Chinese editions |

2.

Qin (for the Chinese edition see below )

2.

Qin (for the Chinese edition see below )

Like her Empire of Living Symbols (above), Qin was has been awarded a number of prizes, including best non-fiction book published in Sweden during 2006. Of its popularity Kristofer Svensson, as of 2014 a graduate student in Music Composition at Hong Kong University, wrote, "Cecilia's book probably had something to do with my interest in qin, that book was such a hit in Sweden, especially amongst musicians. We always find it amusing that literally all musicians in Stockholm have it on their bookshelves."

(Return)

3.

Translation of the Table of Contents and Preface

Provided by Cecilia Lindquist.

(Return)

4.

林西莉:古琴的故事: Chinese translation (covers at right)

Qin has been translated into Chinese (by 許嵐 and 熊彪) and published in both simplified Chinese and standard Chinese: there are at least two editions, China and Hongkong/Taiwan (there may be two different editions of the latter).

(Return)

Appendix

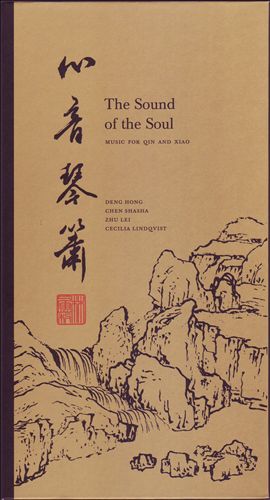

Double CD: The Sound of the Soul (心音琴簫 Xin Yin Qin Xiao)

Guqin played by 鄧紅 Deng Hong, with xiao by 陳莎莎 Chen Shasha and percussion by 朱仁 Zhu Lei

Stockholm, Caprice, 2010

This double CD was recorded in Beijing in connection with a tour to Sweden by Deng Hong, daughter of the well-known qin Wang Di (more under Zha Report on Coverage and her qin song book; qin songs on the CD follow Wang Di's reconstructions as published in 絃歌雅韻 Xian'ge Yayun). Cecilia Lindquist, who had studied guqin with Wang Di, organized the tour and wrote liner notes for the CDs. The liner notes, in both Engish and Chinese, are extensive and very useful. The CD has received a very positive response, including a 5 star rating from Songlines Magazine. There are several points, however, that deserve further comment.

Comments

For the recording the liner notes say that Deng Hong used a qin made by Guan Pinghu himself, with silk strings. According to information she has sent these are both the Taigu strings from Wang Shu-Chee and more recent strings by Pan Guohui (see "availability). As for individual tracks of note:

CD 1, track 4: Tears for Yan Hui (泣顏回 Qi Yan Hui)

As explained in my introduction, this is apparently a 20th century adaptation for guqin of a melody that until 1937 only existed in the oral tradition of other instruments. It has no melodic or lyric connection to the earlier Yan Hui guqin melodies such as Yasheng Cao, Si Xian Cao, Yi Yan Hui, and so forth.

CD 1, track 5: Hearing someone play the flute one night in the town of Luo (春夜洛城聞笛 Chunye luocheng wen di)

This track takes its melody from a piece called Qin Poem (琴詩 Qin Shi), originally published in Qinshu Daquan

Folio 21, where there is a statement that any lyrics of four lines with seven characters each can be applied here (see my further

comment). The CD does not mention the title Qin Shi, saying only that the melody comes from Qinshu Daquan, or use the

original lyrics. Instead it uses as lyrics (apparently sung by Chen Shasha; the CD notes do not seem to identify the singer) a famous Li Bai poem and titling the melody accordingly. The Li Bai lyrics are as follows:

誰家玉笛暗飛聲,

散入春風滿洛城。

此夜曲中聞折柳,

何人不起故園情。

On the CD the lyrics are sung twice (0.25-1.06 and 1.17-2.03), both times accompanied by xiao as well as qin and each time preceded by a brief instrumental prelude. Note that the accompanying liner notes mention Qinshu Daquan but do not give the melody title used in that handbook (Qin Shi) or explain that the lyrics have been changed.

CD 1, track 6: Poem of Bamboo Branches (竹枝詞 Zhuzhi Ci)

This track does a similar pairing with a modified version of the melody

Zhuzhi Ci from the Japanese handbook Toko Kinpu; note that the Li Bai or any other poem with 4 lines of 7 characters each could also be used here (see another example). On the CD the lyrics, in this case actually by 劉禹錫 Liu Yuxi (here sung twice by Chen Shasha), are as follows (see Yuefu Shiji

Folio 81):

楊柳青青江水平,

聞郎岸上踏歌聲。

東邊日出西邊雨,

道是無晴卻有晴。

Wang Di's transcription also has the melody played twice, but she has these lyrics only for the second playing; for the first she sets different Liu Yuxi Zhu Zhi lyrics:

雲間煙火是人家。

銀钏金钗來負水,

長刀短笠去燒畲。

The CD liner notes give the musical source without explaining that the lyrics were changed, presumably by Wang Di herself. The melody has also been changed somewhat from that in Toko Kinpu; this can most easily be heard in the second half of each playing.

CD 1, track 7: Dawn over the Jade Palace (玉樓春曉 Yulou Chunxiao)

The original afterword is somewhat different from here. The melody was originally published as

Chun Gui Yuan, apparently in 1799.

CD 2, track 9: Eighteen Songs about a nomad flute (胡笳十八拍 Hujia Shibapai)

This track has two "songs" (sections) played by solo flute. The source is identified as "Qin Shi", which has tablature identical to that in Luqi Xinsheng (1597). On this recording Chen Shasha plays Sections 1 and 18, following quite closely Wang Di's transcription in Xian'ge Yayun. It might be noted that the original tablature used a scale that is mostly do re mi so la but it also contains a number of notes clearly indicated as do sharp and mi flat; Wang Di's transcription eliminates all these sharps and flats (see Modality in Early Ming Qin Tablature for my argument that these accidental notes were certainly intentional).

Return to the top or to the

Guqin ToC