|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Performance Themes My Performances My Repertoire / Matteo Ricci songs Yang Yinliu hymn Wu Li | 首頁 |

|

Christianity1

and the Qin 2

|

基督教與琴

Matteo Ricci 3 |

My personal focus, and the focus of this website, is with a few exceptions historically informed performance of the early guqin repertoire. As for the present page, it is perhaps more similar to the page Buddhism and the Qin than it is to the pages Daoist Qin Themes or

Confucian Qin Themes.4 For the latter theme there any many relevant melodies to select from. But just as there are few overtly Buddhist melodies for the qin, there are few such overtly Christian melodies other than the modern Christian hymns sung in Chinese.5 Furthermore, this page is not even a remotely comprehensive survey of the topic. Instead it is more of an exploration of some aspects of the topic that hopefully might provide some inspiration for future work on this theme.6

My personal focus, and the focus of this website, is with a few exceptions historically informed performance of the early guqin repertoire. As for the present page, it is perhaps more similar to the page Buddhism and the Qin than it is to the pages Daoist Qin Themes or

Confucian Qin Themes.4 For the latter theme there any many relevant melodies to select from. But just as there are few overtly Buddhist melodies for the qin, there are few such overtly Christian melodies other than the modern Christian hymns sung in Chinese.5 Furthermore, this page is not even a remotely comprehensive survey of the topic. Instead it is more of an exploration of some aspects of the topic that hopefully might provide some inspiration for future work on this theme.6

Along these lines, any program resulting from the exploration here of the topic of guqin and Christianity is likely to be one such as Music from the Time of Matteo Ricci, which imagines an East West encounter. Within that context this arrangement of Matteo Ricci's Eight Song's For Western Keyboard might be compared to modern Chinese hymns that are set to Chinese music, some of which are discussed further below. However, the Ricci program is more of a fantasy that imagines a cultural exchange, allowing us to ponder the differences at that time between Chinese and Western music. And although it features music that Matteo Ricci could have created, it provides no evidence that any local traditions ever developed from this (further comment).

For a more direct approach to this topic, focusing specifically on Chinese Christian music, hymns are potentially the most obvious example. Here, whether the hymns use either Western or Chinese idiom, the vocal lines tend usually to be stepwise, and almost all are harmonized in a Western manner. In contrast guqin melodies are usually played solo, hence monophonic, and the melodic lines are usually more disjunct than stepwise. On the other hand, qin songs tend to be paired to the melodies in a largely syllabic style, as are most Western hymns other than those based on chant. Thus existing melodies can generally be adapted based on the word count. For this see, for example, the word count charts that come with many hymnals and compare that with these guidelines and listings of both regular patterns and irregular patterns for guqin songs.

Within this context, here are four channels that seem to provide the most potential for explorating this topic:

Any music connected to the latter three items has occurred mainly in modern times, though the original texts and/or music might be quite old. Meanwhile, recommendations for further developing this theme would be very welcome.

Here is further detail on each of the above four channels.

Prior to Matteo Ricci's arrival in China in 1580 the written evidence for non-Chinese people hearing Chinese music, or for Chinese people hearing non-Chinese music, is not detailed enough to provide evidence for what the music actually sounded like to them at the time. To put this another way, guqin tablature gives great detail on how to play guqin music, but there is no evidence for people outside of China (unless it was Sinophiles in Japan or Korea) having read it or having seen transcriptions; likewise prior to Ricci there is no evidence for there being knowledge in China of music in

Western notation.

Thus although the program Music from the Time of Marco Polo includes music Marco Polo could actually have heard in China when he claims to have been there (ca. 1280) along with music he could have heard after he returned to Italy (ca. 1300), the sources for the program do not actually name any melodies he may actually have ever heard.

Likewise, with Music from the Time of Matteo Ricci: although I have been able to put together a program on this theme in a way that includes music with which Ricci and/or his fellow Jesuits would have been familiar from back at home, and some of those visitors did comment on the music they had heard in China, the sources of their commentary do not name the melodies they actually did hear.

One idea for a Matteo Ricci program imagines the Jesuits having a

scholarly gathering together with Chinese literati around 1600, with discussions of philosophy accompanied by appropriate Chinese and Western music from that period. Here a particularly interesting topic could concern the "Rites Controversy"

(Wiki): did the Chinese rites connected to ancestors amount to worship or was it merely paying respect. That is one of the thoughts I had when preparing to play the melody

Thinking of Parents

(lyrics) in a memorial garden at the church where their ashes are buried

(video;

further comment).

Many Chinese hymn texts are paired to existing Western hymn melodies, and newly composed hymns tend to be in a Western style. Much fewer come from existing Chinese melodies and only a very few from existing guqin melodies. The similarities described above mean that existing melodies can generally be adapted based on the word count. For this see, for example, the word count charts that come with many hymnals and compare that with these guidelines and listings of both regular patterns and

irregular patterns for guqin songs.

On the other hand, traditional Chinese music tends to be pentatonic but the hymns are almost all diatonic. And guqin melodies are usually played solo, hence monophonic, and the melodic lines are usually more disjunct than stepwise. This as well as the classical language perhaps helps account for the few number of guqin melodies that have been used for Chinese hymns.

The following are the best known examples of Chinese hymns for which guqin song melodies have been adapted.

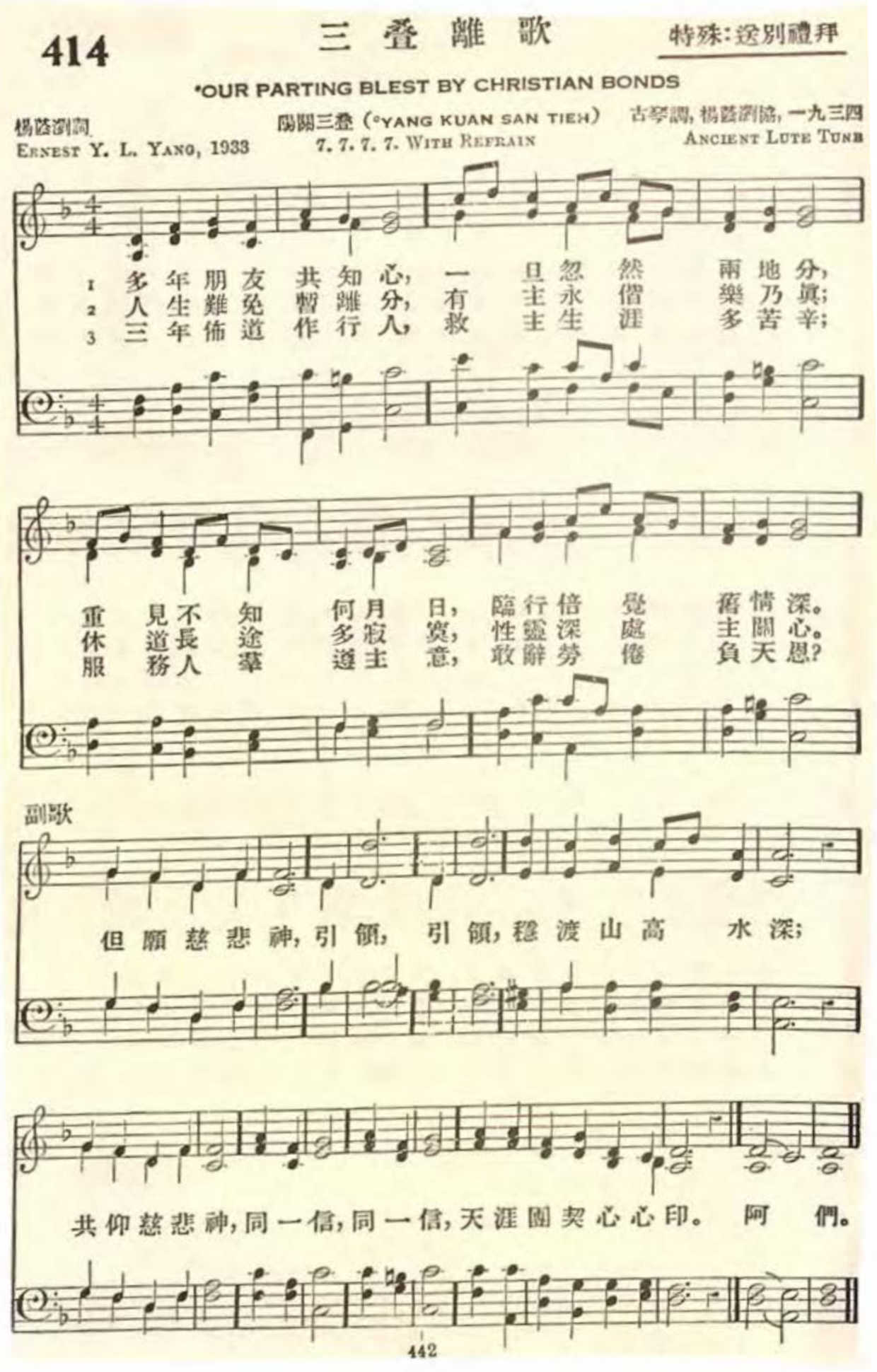

Other than the completely different lyrics

(q.v.), the main differences between the hymn version and the 1530 version of this melody (the earliest short version of a Yang Guan melody) are at the beginning and end. Thus the hymn version drops the opening musical phrase from 1530, jumping right into the main melody. Then, like the original short version the hymn version has three sections, dividing each section in half. But whereas the hymn version has different lyrics for the first half of each section but identical lyrics for the second half of each section, the 1530 version has identical lyrics (the Wang Wei poem) for each first half but somewhat differing lyrics and melody in each second half. The other major difference is that in the original the second "half" of the third section is actually considerably extended with a coda added as well.

The lyrics of 三疊離歌 Sandie Li Ge are as follows:

(副歌 refrain):

(副歌 refrain)

(副歌 refrain)

Recordings of this version sung with chordal keyboard accompaniment can easily be found online. This one on YouTube has English commentary that says the lyrics were inspired by Psalm 100

("Make a joyful noise unto the Lord, all ye lands."). However, the Thessalonians passage with its theme of separation seems more likely.

The lyrics of Zhen Mei Ge begin,

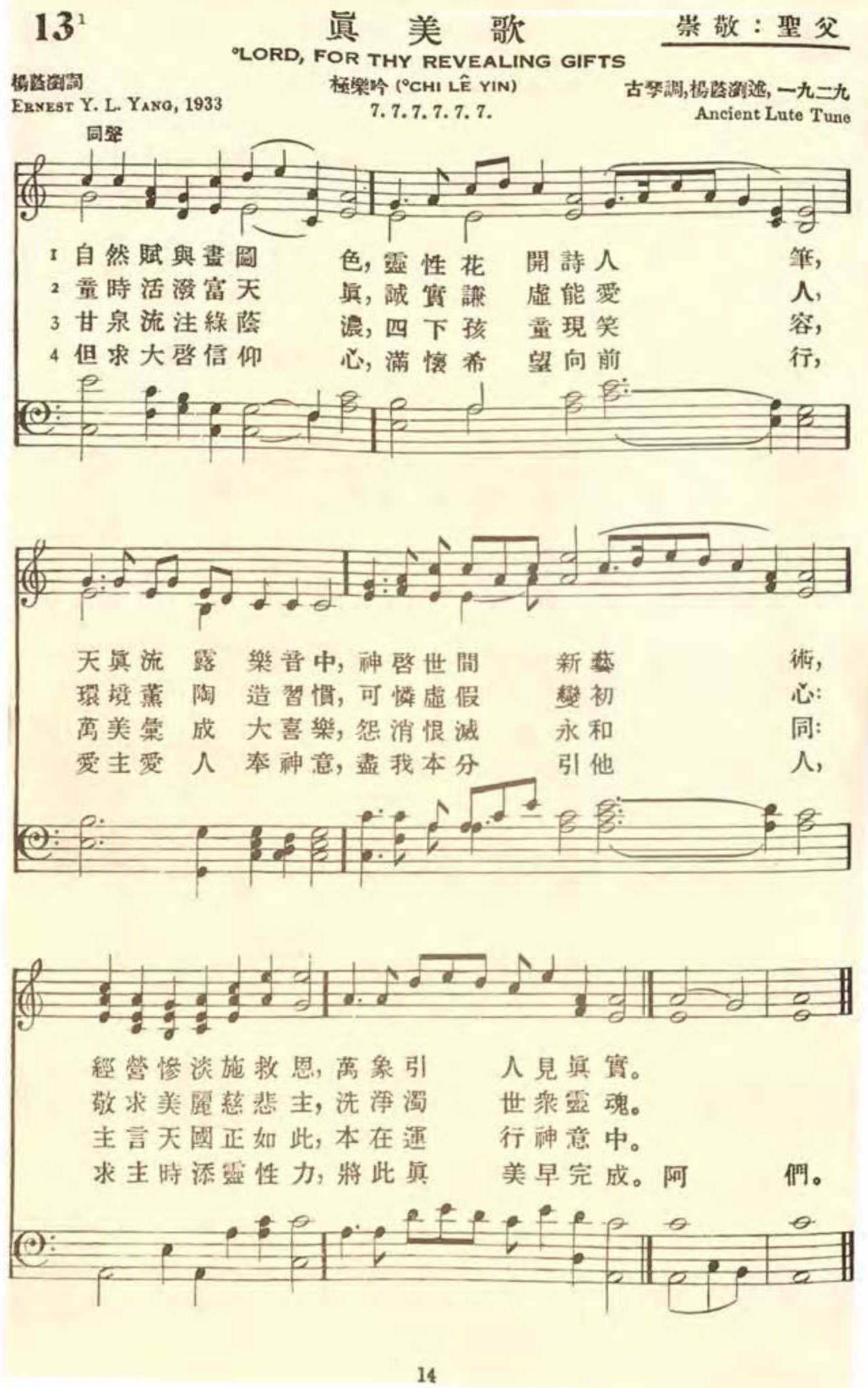

(The melody is repeated five times, each to different lyrics. Note that words in the hymn that have more than one note paired to them are at places where there were slides in the original song, but sometimes the slides are divided up somewhat differently.)

Publication details of these are not yet traced. And more might eventually be added.

In addition, not just existing Chinese songs but also Chinese poetry with a Christian theme can be made into hymns by pairing those poems with the melodies of existing guqin songs. This could be particularly appropriate if the poems were by early Chinese Christian poets such as 吳歷 Wu Li. The classical nature of those lyrics, however, might more likely result in meditations or performance songs rather than participatory hymms. There is further discussion how this might be done in a footnote under Wu Li entitled Setting Wu Li's poems for qin melodies.

Once again, this topic has not yet been fully researched.

1.

Christianity (基督教 Jidu Jiao)

As for Christianity, the first problem in writing this page was selecting a Chinese translation for this title. Dictionaries give 基督教 Jidu Jiao ("Religion of Jesus") as the standard terms for "Christianity", but in common speech it can specifically mean Protestantism in contrast to 天主教 Tianzhu Jiao ("Religion of the Heavenly Lord"), commonly used to refer specifically to (Roman) Catholicism. 基督新教 Jidu Xin Jiao ("New Religion of Jesus") is said to be the specific term for Protestantism, but it is not commonly found in dictionaries.

A search of this traditional encyclopedic dictionary for the earliest mention of Christianity in Chinese writings led to these entries:

The earliest significant interaction between China and the West to have been historically well documented seems to date from around the year 1600, when Matteo Ricci was in China (actually 1583-1609). The above is part of my as yet unsuccessful effort to know for sure what words would have been used in China at that time to refer to Christianity or Christians.

2.

Christianity and the Qin (基督教與琴 Jidu Jiao yu Qin

The next inspiration came from reading Jonathan Chaves, Singing of the Source: Nature and God in the Poetry of the Chinese Painter Wu Li, University of Hawaii Press, 1992. Prof. Chaves then gave me further inspiration by passing on to me information he later published in his article Wu Li's Vision of Zither Music as Resonating with Christianity: Tones of Western Wonders"; Sino-Western Cultural Relations Journal, vol. 36, 2014, pp. 7–13.

Around the same time I discovered that the eminent Chinese musicologist Chinese musicologist Yang Yinliu had early in his career edited and arranged hymns in the earliest extensive Chinese hymnal (1936). I noticed that he paired at least two qin melodies largely following the

standard traditional pairing method (note his use of slides) and was intrigued by the whole concept of pairing qin melodies to religious texts, though to my ears the ethereal nature of the silk stringed guqin sound is perfect for meditation, its melodies need stronger sounds to accompany group singing.

Meanwhile, almost nothing is known about Christian music in China prior to the year 1600. In fact, the same could be said about Western music in general or, for that matter, music from the rest of the world: though China certainly had music instruments that originated outside of China, there is little to no documentation of the music played on them prior to the introduction of Western notation. Even if one expands the topic to the Abrahamic religions in general (to include Islam, which had a significant presence in China, as well as Judaism) there is still virtually no material evidence to work with prior to the 17th century.

This is one reason why study of the guqin is so significant: its written tradition makes it the only non-Western music instrument for which one can provide solid evidence for its claims of antiquity (via HIP).

3.

Image: Matteo Ricci

4.

Comparing the Buddhist and Christian theme

The relatively short history of Christianity in China distinguishes it from Buddhism. And here, although one might imagine a poet such as

Yuan Hongdao playing qin to accompany his Buddhist poetry or Wu Li doing so to accompany his Christian poetry, it is more difficult to imagine local literati living in villages playing on the qin melodies inspired by music they may have heard in church services run by Christian missionaries.

5.

Christian melodies for guqin

6.

Overtly Buddhist or Christian melodies for guqin

7.

Western music settings for the poetry of 吳歷 Wu Li

The Western music within such an encounter could be overtly Christian or it could simply represent the moral and philosophical underpinnings of a largely Christian culture; similarly, the guqin music might at best connect to philosophical themes expressive of Chinese philosophical ways of thought.

Generally speaking, hymns sung in Chinese are like hymns sung in English, with the words paired in a largely syllabic manner (i.e., a similar number of syllables to the number of notes, so not melismatic) and with the vocal lines usually stepwise (for ease of singing, so not disjunct); almost all have been harmonized in a Western manner.

)

- very similar to the

1530

Yangguan Sandie

(trace, and compare my recording from 1530)

pdf from the hymnal

The prominent Chinese musicologist Yang Yinliu harmonized this version of this old qin melody and also created Christian lyrics for it in Chinese. This was then published in the Protestant hymnal called Hymns of Universal Praise (普天頌讚 Pu Tian Song Zan;

Wiki; 1936 and since re-issued), for which he was a primary editor. Yang, who had graduated from St. John's University in Shanghai

(Wiki) and was then a practicing Anglican, arranged a number of melodies in that hymnal. The lyrics, which begin with separation then have a refrain that speaks of travel, are clearly connected to the theme of Wang Wei's poem, but they are said also to have been inspired by a Biblical verse, 1 Thessalonians 2, 17: "But, brothers and sisters, when we were orphaned by being separated from you for a short time (in person, not in thought), out of our intense longing we made every effort to see you." (NIV)

The prominent Chinese musicologist Yang Yinliu harmonized this version of this old qin melody and also created Christian lyrics for it in Chinese. This was then published in the Protestant hymnal called Hymns of Universal Praise (普天頌讚 Pu Tian Song Zan;

Wiki; 1936 and since re-issued), for which he was a primary editor. Yang, who had graduated from St. John's University in Shanghai

(Wiki) and was then a practicing Anglican, arranged a number of melodies in that hymnal. The lyrics, which begin with separation then have a refrain that speaks of travel, are clearly connected to the theme of Wang Wei's poem, but they are said also to have been inspired by a Biblical verse, 1 Thessalonians 2, 17: "But, brothers and sisters, when we were orphaned by being separated from you for a short time (in person, not in thought), out of our intense longing we made every effort to see you." (NIV)

重見不知何月日,臨行倍覺舊情深。

但願慈悲神,引領,引領,穩渡山高水深;

共仰慈悲神,同一信,同一信,天涯團契心心印。

休道長途多寂寞,性靈深處主關心。

服務人群遵主意,敢辭勞倦負天恩?

- based on the

1931 version of

極樂吟 Ji Le Yin

(compare this pdf with

the second half of this one

[details])

pdf from the hymnal

In the same hymnal mentioned above Yang also made Hymn 13, Lord, For Thy Revealing Gifts (真美歌 Zhen Mei Ge) by creating Christian lyrics that could be paired to the melody Ji Le Yin as published in the Meian Qinpu (1931); the original lyrics there had been those by Liu Zongyuan as in the >1505 melody Yu Ge Diao. By comparing the published hymn at right with this transcription it can be seen that the pairing method here is very similar to that of the

standard pairing method once used for almost all guqin songs.

In the same hymnal mentioned above Yang also made Hymn 13, Lord, For Thy Revealing Gifts (真美歌 Zhen Mei Ge) by creating Christian lyrics that could be paired to the melody Ji Le Yin as published in the Meian Qinpu (1931); the original lyrics there had been those by Liu Zongyuan as in the >1505 melody Yu Ge Diao. By comparing the published hymn at right with this transcription it can be seen that the pairing method here is very similar to that of the

standard pairing method once used for almost all guqin songs.

天真流露樂音中,神啟世間新藝術,

經營慘淡施救恩,萬象引人見真實。

Later another Chinese Christian, 陳澤民 Chen Zemin (1917-2018), is said to have adapted least three guqin melodies to make hymns. These were included in The Chinese New Hymnal (available in both number [1983] and staff [1983] notation) 《讚美詩(新編), also 1998 ?》

Although this is said to come from one or more of the versions of the qin melody 平沙落雁 Pingsha Luo Yan, the connection is very hard to hear.

Uses the musical refrain from 梅花三弄

Meihua San Nong.

"中國古琴曲 Chinese guqin piece": said to be related to either

釋談章 Shi Tan Zhang or

釋談章 Pu'an Zhou, but again the connection is difficult to hear.

There have been many arrangements of Western hymns into the Chinese language, mostly using versions of the original Western hymn melodies but also with newly composed melodies.

Many new melodies have made in Western style, fewer in Chinese style, to accompany Christian or Christian-themed lyrics and poetry (for example, Western music settings for Wu Li's poetry6), but to my knowledge none has been created specifically for guqin.

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

It could be interesting to broaden this topic to add Judaism and Islam and thus explore all connections any of these could have to guqin. However, for these latter two I have only found a qin connection with the Hui Muslims in Hangzhou, who from the Qing dynasty were making a well-known quality of silk string qin strings under the trade name Hui Hui Tang.

(Return)

My first work on this topic came from hearing clavichord performances at the Boston Early Music Festival in 2005, where I heard some recitals for clavichord and felt a kinship with the quiet output of that instrument. I read that Matteo Ricci may have brought a clavichord to China and so I began working on the ideas described here on the page Music from the Time of Matteo Ricci

(Return)

See more under Music from the Time of Matteo Ricci.

(Return)

Comments here concern fertile areas for exploration but my relative ignorance. Thus, for example, there are historically few qin melodies on an overtly Buddhist theme, there is much overtly not to mention subliminally Buddhist poetry. Because qin has a strong written tradition people tend to forget it was at least as much an oral tradition. (My original qin teacher told me to watch him, not look at the tablature; see also my comment on

"composers".) So just because there is no written evidence for this does not mean that poets who were qin players never had existing qin melodies or Buddhist temple music in mind when writing Buddhist-themed poems, whether they paired them in the traditional written manner or not.

(Return)

As mentioned above, although there are no traditional guqin melodies specifically connected to Christianity, there are a number of hymns that might be useful for this theme by expanding on those discussed here.

(Return)

Although overtly Buddhist qin melodies may be few, from very early years Buddhist ideas had already permeated Chinese ways of thought so much that one can point to what in Chinese culture seems also innately Buddhist. Matteo Ricci might have been attempting to do the same for Christianity; others were much less ecumenical. The discussion continues today.

(Return)

Examples of this are mentioned under Wu Li.

(Return)

Return to the Guqin ToC