|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| XLTQT Original ToC Comments Tunings Zha preface Tang Gao preface Wang Zhi preface Further | 首頁 |

|

Pursuing Antiquity

1

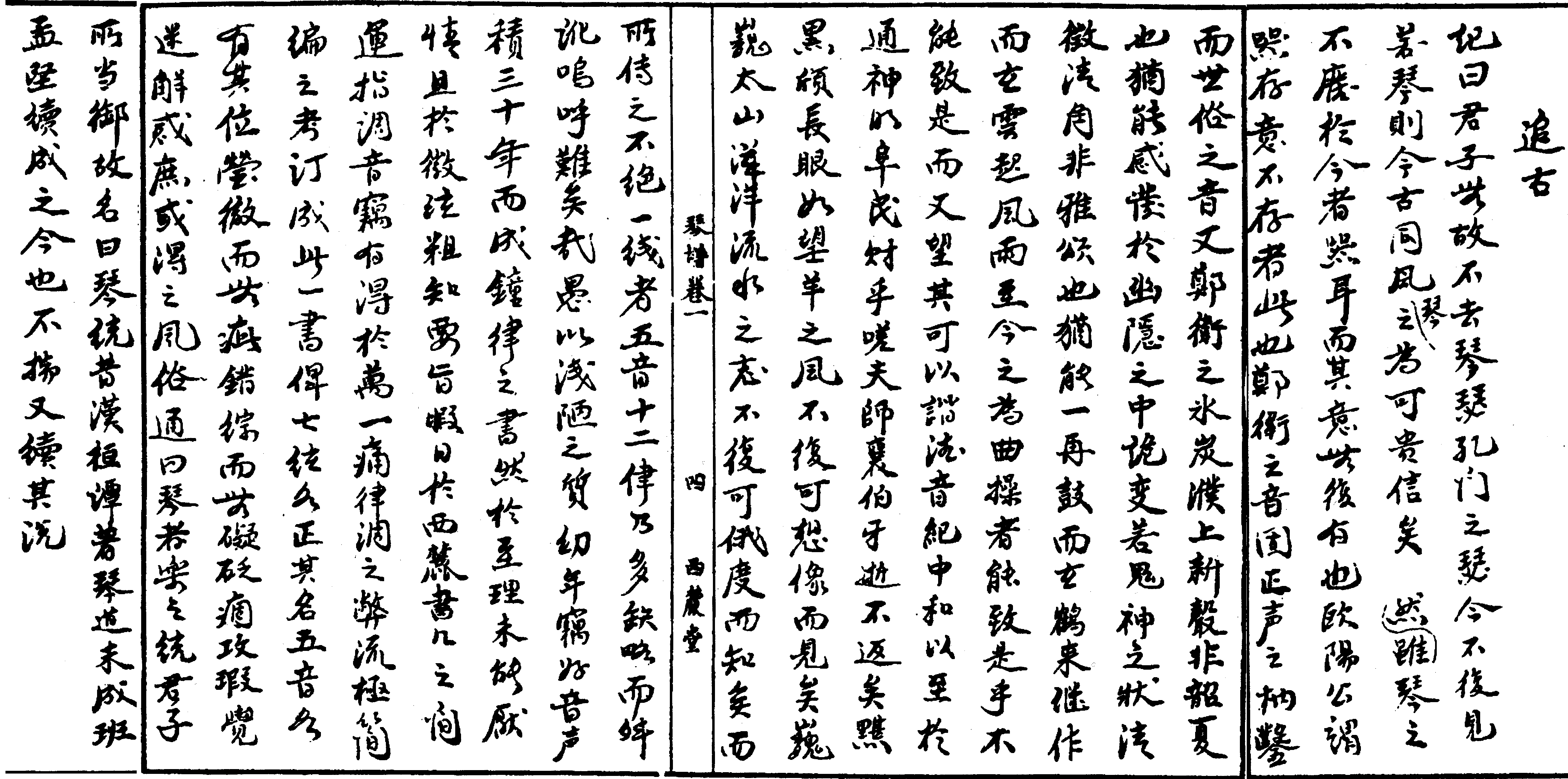

from Xilutang Qintong (1525; QQJC III/11-12) |

追古

作者:汪芝 |

| Original text; Enlarge |

This essay, like the Preface to Further Essays, was also copied into Qinshu Cunmu, where it is attributed to Xu Li, original author of the Qin Tong. The copy there was printed and much more clear than the handwritten copy at right, so it was used here for characters that I could not figure out from there. However, it also has a number of additions, though the only significant one has been copied here into a footnote. The reason for this is unknown.2

This essay, like the Preface to Further Essays, was also copied into Qinshu Cunmu, where it is attributed to Xu Li, original author of the Qin Tong. The copy there was printed and much more clear than the handwritten copy at right, so it was used here for characters that I could not figure out from there. However, it also has a number of additions, though the only significant one has been copied here into a footnote. The reason for this is unknown.2

Here is my translation along with the original text.3

Pursuing Music

(The Book of Music) records that, "A gentleman, without good reason, does not cast aside qin and se". The se of Confucius’ school is today no longer seen. As for the qin, it nature has remained the same from ancient times to the present. That the qin is indeed precious, this is most emphatically true. And yet, what has not been lost in our time is merely the instrument itself, its true purpose no longer survives.

『(樂書)』記曰:君子無故不去琴瑟。孔門之瑟,今不復見。 若琴,則今古同風。琴之為可貴,信矣。雖然,琴之不廢於今者,器耳,而其意無復有也。

Master Ouyang (Ouyang Xiu) once said, "The instrument remains but its true purpose is gone;" this is precisely that case. The music of Zheng and Wei was clearly incompatible with proper sound, like mortise and tenon that do not fit; and the popular music of today is yet another form of that Zheng and Wei music — mutually destructive, like ice and hot coal. (And the lascivious) "new" sounds of Pu are not (the noble music of) Shao (for Emperor Shun) and Xia (for the Xia dynasty). Even though it is still the case that one can stir hidden feelings, transforming strangely like the manifestations of spirits and demons. the qingzhi and qingjue modes are not part of the (refined) Ya and Song tradition. (And) even though it is still the case that (if you use them like Shi Kuang) you can strike (the qin) once or twice and dark cranes come; then play again and dark clouds gather, wind and rain arive.

歐陽公謂:「器存而意不存者」,此也。 鄭、衛之音,固正聲之枘鑿;而世俗之音,又鄭、衛之冰炭。 濮上新聲,非韶夏也,猶能感發於幽隱之中,詭變若鬼神之狀。 清徵清角,非雅頌也;猶能一再鼓而玄鶴來,繼作而玄雲起風雨至。

Are those who today create and perform music able to achieve this? If they cannot, how can they still hope that their music might harmonize with proper tones, regulate balance and concord, and ultimately communicate with spirits above and enrich people below?

今之為曲操者,能致是乎?不能致是,而又望其可以諧諸音,紀中和,以至於通神明、阜民財乎?

Sadly, (masters such as) Shi Xiang and Bo Ya are long gone, never to return. (The former), a dark and tall figure — as untrammeled as wind inclining towards a distant flock — can no longer be imagined or seen. (The latter), with lofty ambitions firm as Mount Tai, and a spirit flowing like mighty waters, can no longer be glimpsed in a moment, nor grasped with sudden insight. And what remains of the singular unbroken thread of tradition - the five tones and twelve pitches - is now largely fragmented, incomplete and riddled with error.

嗟夫,師襄、 伯牙, 逝不返矣。黮黑頎長,眼如望羊之風,不復可想像而見矣。 巍巍泰山,洋洋流水之志,不復可俄度而知矣。 而所傳之不絕一綫者,五音十二律,乃多缺略而舛訛。

Alas, how difficult it is!

Though foolish with my shallow and vulgar nature, in my youth I privately loved the sound of music, and now after thirty years I have completed a treatise on tuning and mode.

(Qinshu Cunmu inserted a passage here)

And even now when it comes to these principles I have not lost interest.

As for dealing with the actual finger positions and strings (Does this mean playing? Otherwise he says very little about that.), I have only a rough understanding of the essentials. In quiet days, at my desk beneath the Western Foothills,

I practice fingerings and adjust tones, and sometimes find a faint glimpse of what is true.

But then, troubled by flaws in the tuning systems, I pour myself into organizing these tunings, then revising them into this one work. (Is Wang Zhi here suggesting when he plays the melodies he finds they don't fit into the musical system as he understands it, so he then spends a lot of time looking at the 170 melodies he has included in this collection, trying to determine such things as into what mode they should be grouped?)

Each of the seven strings (to be played) is now clearly named;

each of the five tones is restored to its proper place (this is poetic license: the handbook includes many melodies that are not purely pentatonic).

These gems should be clear as crystal, and errors arranged so there are no problems.

May it thus cut through what is flawed, correct what is errant, awaken the lost, clarify the confused and, perhaps in some small way, achieve this goal.

嗚呼,難矣哉! 愚以綫陋之質,幼年竊好音聲, 積三十年而成鐘律之書。(「琴書存目」在此插入一段。) 然於至理未能厭情,且於徽、絃,粗知要旨。 暇日於西麓書几之間,運指,調音,竊有得於萬一。痛律調之弊,流極簡編之,考訂成此一書, 俾七絃各正其名,五音各有其位。 瑩徹而無疵,錯綜而無礙。 砭㽽攻瑕,覺迷解感,庶或得之。

According to the Feng Su Tong, the qin is the unifying form of music in the world, what the gentleman ought to master. So I have named this work 琴統 Qin Tong — "Qin System."

《風俗通》日,琴者樂之統,君子所當御,故名曰《琴統》。

Long ago, Huan Tan of the Han dynasty wrote a 琴道 Qin Dao, but it was unfinished; Ban Mengjian (Ban Gu) then resolutely continued the work and completed it. And now I without daring to presume am continuing this discussion.

昔漢桓譚著《琴道》,未成;班孟堅續成之。今也不揣又續其說。

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

1.

Pursuing Antiquity texts (An essay in Qin System from the Hall of the Western Foothills)

This preface has also been translated by Peiyou Chang -- see

her website.

(Return)

2.

Version in Qinshu Cunmu#112.

This has some passages that are not in the Xilutang Qintong version. Perhaps they were in the original Qin Tong by Xu Li (see his bio.) Two examples of these could well date from the time of Xu Li:

- The essay begins "記曰", quite likely intending it to mean "『禮記』曰 The Book of Rites said". Here QSCM added "者" so that the passage would mean "A writer said". In fact, though, this is a quote from 陳暘,樂書 the Book of Music by the Song dynasty writer Chen Yang (see quote in ctext). Chen apparently often paraphrased ancient quotes, this one from 禮記,曲禮下 The Book of Rites, Summary of the Rules of Propriety, Part 2. There the full quote (see ctext) is, "君子無故,玉不去身,琴瑟不輟於口。Unless there is good reason, the gentleman does not part with jade from his person, nor does he cease to speak of (or play) the qin and se."

- In the second line of the text someone made a mark to show that the characters "雖然" had been reversed.

- This, the main insert, is quite long. It is also quite strange. The original text both here and in Qinshu Cunmu is unpunctuated. There are a few places where there seem to be a few words inserted, but here Qinshu Cunmu version inserted the following personal note from what seems to have been 270 years earlier right in the middle of a sentence, here. As can be seen from the date alone (during the reign of 宋理宗 Song Lizong [r. 1224-1264]) it cannot be related to Wang Zhi: some paper the compiler or Qinshu Cunmu had on his desk? Here is the content (it does mention qin):

In the yimao year of the Baoyou reign [1255], this was presented to Emperor Lizong. His Majesty’s words were passed on to the Commissioner of Records, the Upright and Enlightened Lord You, who reviewed it thoroughly. At that time, I was assisted by the guidance of the elder statesmen and worthy gentlemen, and thus was fortunate to receive the rare favor of being appointed to the Office of the Imperial Secretariat — a chance in a thousand. This year, I have already passed the age of fifty-one. My years of official service have gradually withered, like ashes; I have yet to find peace in ultimate truth. Yet in the subtle methods of qin music, I have grasped some essentials. These reflections were written on a quiet day in my bamboo study. 寶祐乙卯,獻於理宗皇帝。 玉音付提史端明尤公,淆看詳。一時元老諸賢汲引,遂得叨司科給事千一之遇也。 今年五十踰一矣。仕進之年,浸若槁灰然;於至理未能厭情,且於徽法粗知要旨。暇日於竹齋書。

3. Further explanations

- 鄭、衛之音 "sounds of Zheng and Wei" has long been an expression for "low class" (for want of a better term) music, from Lüshi Chunqiu (ctext).

- "濮上新聲 New sounds from On the Pu": also bad. The same passage in Lüshi Chunqiu, says "桑間濮上之音,亡國之音也 Music from 'Midst Mulberries' and 'On the Pu (river)' was that of a state going to ruin. 15030.90 桑間濮上 says, "謂淫風流行之地 this was a place where the customs of the (corrupt) state of Yin were popular. 桑間 Sangjian and 濮上 Pushang are themselves said to have been place names in what is today Henan pro]vince (see under Zhou Xin).

- 雅頌 Ya Song (odes and hymns): traditionally refers to Chinese court music.

(Return)

Return to the annotated handbook list or to the Guqin ToC.