|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Art Illustrating Guqin Melodies Chu performance theme | 首頁 |

|

Scenes Illustrating Poems in "Poetic Feelings of Ancient Sages"1

Painting by Du Jin;2 calligraphy by Jin Cong3 |

古賢詩意圖 Gu Xian Shi Yi Tu Illustrations

明杜堇畫圖、金琮書詩 |

According to the postscript by Jin Cong this scroll, in the collection of the Palace Museum, Beijing, includes 12 poems and 9 related images. The existing version, linked here in two parts with images going right to left, seems in fact to have only 11 poems. The last three poems are presumably considered to be a set and so have only one illustration.4

The standard complete entries are arranged with the poem title first, then the poem itself followed by the illustration (it is unclear why #s 1, 3 and 8 omit the title). Some entries, however, omit the title. What follows is an outline of the scroll as it actually exists today.

- (Li Bai:)

Youjun and a Caged Goose (右軍籠鵝 Youjun Long E)

This presumably should be the title of the first entry, but the entry does not actually have a written title. The "Youjun" in the title refers to the famous calligrapher Wang Xizhi (see in particular 《晉書》卷八十〈王羲之列傳)). Wang was from Shandong but lived much of his life in an area of Shaoxing then known as Kuaiji Shanyin. He was known to be fond of geese, in particular for the graceful way they fly. Interestingly, though, the Chinese character used here for geese is 鵝 e (domestic goose), not 雁 yan or 鴻 hong (wild geese). The former seems never to be used in connection to qin melodies.The poem by Li Bai as included here is as follows,5

右軍籠鵝:李白詩《王右軍》) 右軍本清真,瀟灑在風塵。 Yòu jūn běn qīng zhēn, xiāo sǎ zài fēng chén.

山陰遇羽客,要此好鵝賓。 Shān yīn yù yǔ kè, yào cǐ hǎo é bīn.

掃素寫道經,筆精妙入神。 Sǎo sù xiě dào jīng, bǐ jīng miào rù shén.

書罷籠鵝去,何曾別主人。 Shū bà lóng é jŭ, hé céng bié zhǔ rén.(Wang) Youjun was true and pure by nature, free and easy amidst the dust of this world.

Whenever in Shaoxing he met feathered guests, he would treat them as honored guest geese.

With brush in plain style he wrote out the Dao classic, the brushwork's beauty becoming spiritual

The calligraphy was finished and caged goose was in hand, how else could it have left its master?The image here shows two men, one speaking to the other at a table; the one at the table, presumably Wang Xizhi himself, is holding a writing brush. On the table is an inkstick leaning on an inkstone, with two scrolls rolled up alongside. In the middle is a servant with a caged goose. This as well as the poem itself connects this entry to a story that says a man with a goose once asked Wang Xizhi to write out for him the text of the Dao De Jing; in return Wang asked for a goose (see also this other version). For another relevant image dating from perhaps a century later than Du Jin's see this image by 陳洪綬 Chen Hongshou (1598-1652; Wiki).6

- (Han Yu:) Peach Blossom Spring (桃源圖 Tao Yuan Tu)

The second entry, translated more literally as Peach Spring Illustration ("blossom" being implied), has all the standard components for the scroll: first the image, then the title, then the poem itself. The poem, by Han Yu, was presumably inspired by Tao Yuanming's earlier poem on the same topic as was one by Wang Wei, both mentioned here in connection with the qin melody 桃源春曉 Tao Yuan Chun Xiao. Han Yu's poem is as follows:神仙有無何渺茫,桃源之說誠荒唐。

流水盤回山百轉,生綃數幅垂中堂。

武陵太守好事者,題封遠寄南宮下。

南宮先生忻得之,波濤入筆驅文辭。

文工畫妙各臻極,異境恍惚移於斯。

架岩鑿谷開宮室,接屋連牆千萬日。

嬴顛劉蹶了不聞,地坼天分非所恤。

種桃處處惟開花,川原近遠蒸紅霞。

初來猶自念鄉邑,歲久此地還成家。

漁舟之子來何所,物色相猜更問語。

大蛇中斷喪前王,群馬南渡開新主。 (群馬=4+1馬? 262.639「五馬渡江」指的是中國西晉於311年遭逢永嘉之亂?)

聽終辭絕共淒然,自說經今六百年。

當時萬事皆眼見,不知幾許猶流傳。

爭持酒食來相饋,禮數不同樽俎異。

月明伴宿玉堂空,骨冷魂清無夢寐。

夜半金雞啁哳鳴,火輪飛出客心驚。

人間有累不可住,依然離別難為情。

船開棹進一回顧,萬里蒼蒼煙水暮。

世俗寧知偽與真,至今傳者武陵人。Here is a translation largely based on this Google translation into modern Chinese:

It is still very unclear whether gods exist or not,

and the legend of a Peach Blossom Spring Wonderland sounds like fantasty.

The scene of flowing water circling around the mountains with hundreds of twists and turns,

is shown in several pictures painted on raw silk hung in central halls.

The prefect of Wulingshou was a person who liked to paint;

He inscribed a picture of the Peach Blossom Spring, put it in an package and sent it to Nangong Palace (in the distant capital, Luoyang).

A Nangong Palace elder was very happy to get the scroll,

With vigorous strokes the picture had been inscribed.

The picture was wonderful and lifelike, the articles exquisite and steady,

a strange fairyland seemed to have been moved there.

The picture showed houses carved into the rock walls of the valley;

Houses followed houses, and walls followed walls.

Of Qin's collapse and Han's demise they had never heard,

they simply were not aware of all the changes in the world.

Peach trees planted all around inevitably bloomed,

and all along the river evaporated into brilliant red clouds.

When (the fisherman) had first arrived there, he still missed his hometown,

but after a long time, this place became his home.

People there didn't know where the fisherman in the boat came from;

Based on his different appearance, people speculated and asked him about it.

The fisherman talked about (Liu Bang's) killing a serpent and getting rid of the (Qin Dynasty);

And (Sima clansmen?) coming south and (something leading to someone) beginning to rule (from Luoyang, 266-311?).

After listening to the (fisherman's) narration everyone sighed sadly.

They said that it had been six hundred years since he had gone away.

In those days many events were seen to happen,

but we don’t know how much of that is still ind circulation today.

Everyone rushed to entertain the fisherman with food and wine;

But their etiquette and utensils were very different.

The fisherman slept alone in the empty jade hall on a moonlit night, his bones cold and his soul clear;

He felt that all his thoughts were gone and he did not dream a single dream.

In the middle of the night, he heard a golden rooster crow,

and when the sun came out the fisherman felt his heart beat faster.

He felt tied to his family so he didn't dare stay there too long;

In the end, he left the fairyland with a feeling of reluctance to say goodbye.

After the boat started, he paddled forward then turned his head and looked back;

but all he saw in the twilight was vast patches of water.

How can ordinary people in the world know whether this place is real or not?

Until this day the residents of Wuling still relate this story.There are no known qin settings of these lyrics. Could a song by made by creating a new melody following the traditional pairing formula described here with inspiration from the pattern of one or more of the melodies listed here (many are [7+7] but none is [7+7] x 19)?

There is further comment on this painting in this introduction by 商偉 Shang Wei to Volume 2 Issue 1 of the Journal of Chinese Literature and Culture, which has on its cover a copy of the painting here. Professor Shang's article concerns the "complex negotiations and interplay" between word and image, something very relevant to attempts on this site to show how the same literati might also bring guqin music into the mix.

The poem and illustration seem intended to express the reaction of Han Yu upon seeing a picture depicting the Peach Blossom Spring and recalling the poem about it written by Tao Yuanming. There are several stories connected to this mythical place, such as the one told with the melody Spring Dawn at Peach Blossom Spring of a fantasy trip by a fisherman to Wuling Spring (in Hunan, but compare it to the story of two medical plant gatherers going to 桃源 Peach Blossom Spring near 天台山 Tiantai Mountain, set for qin in the melody Tian Tai Yin). In addition there is the melody called Spring Dawn at Peach (Blossom) Garden (桃園春曉), as discussed here

-

(Li Bai:) Raising a glass (of wine) and asking the Moon (把酒問月 Ba Jiu Wen Yue; my translation is with

this qin setting)

This title, though missing here, should clearly be the title for the third entry. The image is clearly connected to the poem here by Li Bai: the image shows someone sitting at a table. seemingly raising a wine cup (the image attached here does not show his hand clearly, but standing next to him is a servant holding a pitcher); through the trees there seems to be a faint outline of the moon. There have been a number of translations of the poem, such as the one by Sun Yu in Li Po, a New Translation, p. 232 (Questioning the Moon While Drinking); several others can be found online. The original words of the poem are used as lyrics for a melody of this title in Lixing Yuanya (1618; QQJC VIII/241). The 1618 melody is for seven-string qin, standard tuning, jue mode; the original 1618 text, given below, is for a setting that actually divides Li Bai's poem into two sections, as follows:青天有月來幾時?我今停盃一問之。 Note that in several places the text here is different from the version on the scroll at top: the text of the scroll isn't completely clear; the versions that I have noticed are different from the song text have been put in parentheses to the right of the printed lyrics. The most significant difference is perhaps the last character of row five, 憐 lian (pity) instead of 鄰 lin (neighbor).

人攀明月不可得,月行却與人相隨。

皎如飛鏡臨丹闕。緑煙㓕盡清輝發。 (㓕 = 滅 = 灭)

但見宵從海上來,寧知曉向雲間沒。

玉兔搗藥秋復春,姮娥孤栖與誰憐? (白兔搗藥秋復春,嫦娥孤棲與誰鄰?)

今人不見古時月,今月曾經照古人。古人今人若流水,共看明月皆如此;

唯願當歌對酒時,月光常照金樽裡。 (尊) - (Han Yu:)

Listening to Reverend Ying play the qin (聽穎師彈琴圖 Ting Ying Shi Tan Qin Tu)

This, the fourth entry, has an image of someone (presumably Reverent Ying himself) seated on the ground and holding a qin with his right and while the left hand seems to be resting on the ground (this is not clear and the qin strings seem to have been rubbed out!). A companion is seated in the foreground with an unidentified object on the ground to his right. Meanwhile a third person standing to our left seems to be scratching his head. The poem by Han Yu begins as follows:昵昵兒女語,恩怨相「爾汝」。 Affectionately whispering, a young boy and girl speak; in fondness or anger they (call) each other "dear". The poem is translated here together with its setting to a qin melody entitled Intonation on Listening to a Qin.

- (Lu Tong:) Song of Tea (茶哥 Cha Ge)

The fifth entry poem, by Lu Tong (790-835), is best known for its enumeration of the results from drinking each of seven cups of tea, was set to a qin melody, also called Song of Tea, in Lixing Yuanya (1618). The complete poem is given here with translation. It begins,"軍將打門驚周公 As the sun rose late one morning an envoy knocked on the door jolting (me from) a dream." Following on this, the image shows a man in armor knocking on a gate while another person sleeps inside.

- (Du Fu:) Song of the Eight Drinking Immortals (飲中八仙歌 Yinzhong Ba Xian Ge)

The sixth entry illustrates a poem of this name by Du Fu (omitting 歌 ge []song] from the title). The immortals are introduced here and the poem itself is copied out below that, here. As for the qin setting, it is in the same 1618 handbook as above. The poem begins,知章騎馬似乘船,眼花落井水底眠。 He Zhizhang rides his horse as if sailing on a boat; spots in his vision, he falls in a well and slumbers underwater. This translation with the complete poem can be found here (#2.1.) It has the form (7x17; compare the seven character-per-line lyrics here) and a strange non-standard tuning (raised 7th string).

The image on the scroll (see the first image on the second half of the scroll as shown above) shows these eight "immortals" drinking as one of them, on a horse, seems to be directing a laborer arriving with 麴車 a wheelbarrow carrying "qu", a substance used for fermenting wine. A person to the far left is presumably a servant pouring wine. The poem by Du Fu describes this, but the qin setting uses a strange tuning and I have not yet studied it.

- (Du Fu:) Banquet by East Mountain (11.64 東山宴飲 Dongshan Yanyin)

The seventh entry is accompanied by the following Du Fu poem that has the full title 陪王侍御同登東山最高頂宴姚通泉晚攜酒泛江 (In the Company of Attendant Censor Wang, We Climbed the Highest Peak of East Mountain Where We Were Feasted by Yao of Tongquan; In the Evening We Took Ale and Went Boating on the River). This poem, with complete translation, can be found at 11.64. here. A number of the songs listed here have lines of 7+7 characters, but none have precisely the structure here, ([7+7] x 10).姚公美政誰與儔,不減昔時陳太丘。 Who is the match of the excellence of Lord Yao’s governing?— it is no less than Chen Shi of Taiqiu in the olden days.

邑中上客有柱史,多暇日陪驄馬游。

東山高頂羅珍羞,下顧城郭銷我憂。

清江白日落欲盡,復攜美人登彩舟。

笛聲憤怨哀中流,妙舞逶迤夜未休。

燈前往往大魚出,聽曲低昂如有求。

三更風起寒浪湧,取樂喧呼覺船重。

滿空星河光破碎,四座賓客色不動。

請公臨深莫相違,回船罷酒上馬歸。

人生歡會豈有極,無使霜過沾人衣。The accompanying image shows three people (Du Fu, Yao Tongquan and Wang Shiyu?) sitting at a table, attended by a serving boy bringing wine. To the left a boat can be seen in the background, suggesting this is the boat on which they will take the evening ride Du Fu describes in the poem.

- (Huang Tingjian:) Rhapsody on Narcissus flowers (詠水仙 Yong Shuixian)

The eighth entry, which has no title, begins with a poem by 黃庭堅 Huang Tingjian (1045-1105) called "王充道送水仙花五十枝欣然會心為之作詠 Wang Chongdao sent me fifty narcissus blossoms and I happily wrote a poem for him".凌波仙子生塵襪,水上輕盈步微月。 (1696.30 凌波仙子 is another name for the narcissus) The related image then shows a man sitting on the ground at a long low table; in the foreground are a row of plants that look like they could be shuixian. On the table is a container: does it contain 50 "shuixianhua": narcissus blossoms? ("五十枝" in the title perhaps suggests 50 complete plants.) The use of "shuixian" in qin melodies is discussed here, but see also here.

是誰招此斷腸魂,種作寒花寄愁絕。

含香體素欲傾城,山礬是弟梅是兄。

坐對真成被花惱,出門一笑大江橫。- Three poems by Du Fu

The scroll ends with three more poems, all by Du Fu, then a postscript and a ninth image. Only the first poem is given a title. The first two poems are also next to each other in the Complete Tang Poems as well as in this complete Du Fu poetry translation, The Poetry of Du Fu.The three poems (then image) are as follows (title and first lines translated from the complete translation; the rest translated with help from Zhu Yuanhu; no specific guqin connections.

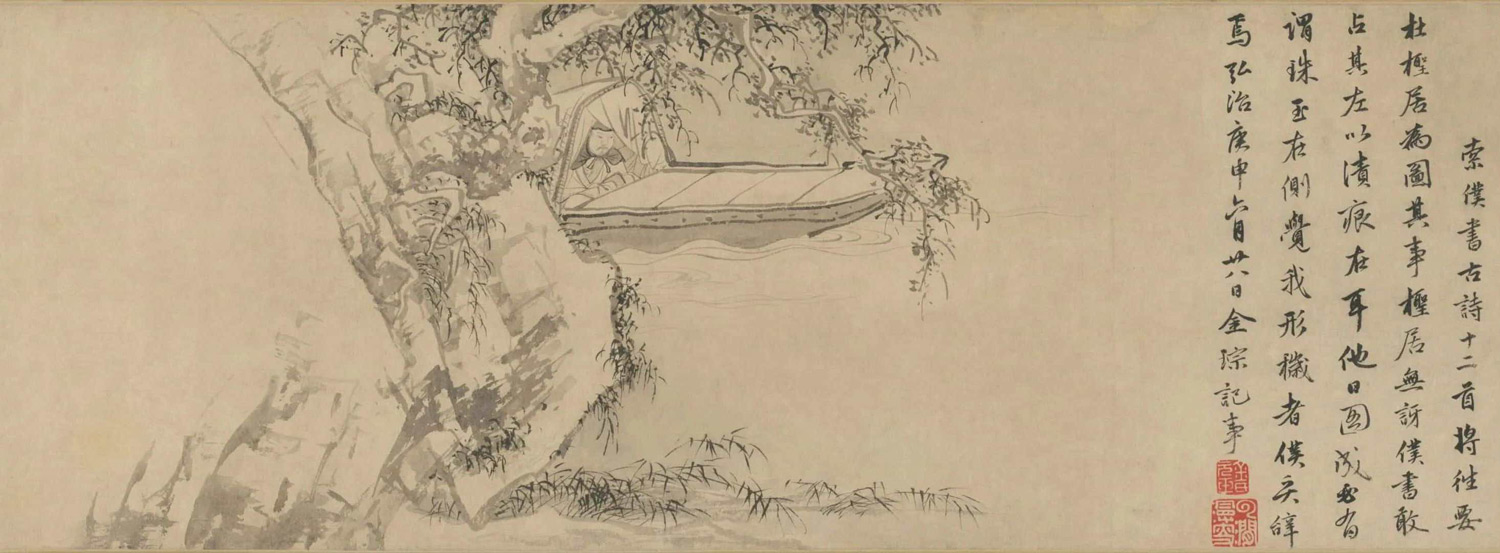

- (Du Fu:) Night Snow on My Boat: Thoughts on Censor Lu

(23.13 舟中夜雪有懷盧十四侍御弟)

This poem is also known by a shortened title, 雪舟中夜 Xuezhou Zhongye: Snow on a boat at midnight). The poem, by Du Fu, is as follows,朔風吹桂水,朔雪夜紛紛。 (Northland winds blow the Gui’s waters, a great snow comes thick at night.)

暗度南樓月,寒深北渚雲。 The moon over the south tower moves quietly, and clouds heavy from the chill are over the north lake.

燭斜初近見,舟重竟無聞。 The candle’s light becomes dim and shaky, to see it clearly I must come nearer. The boat becomes indistinctively heavy though not noticeably.

不識山陰道,聽雞更憶君。 I don’t know the way to Shanyin County. When I hear the cock crowing, I miss you very much.Note: The mention of Shanyin County alludes to the story of Shanyin resident 王子猷 Wang Ziyou visiting a friend in winter .

Goes with image at end.

- Facing the Snow (23.14 對雪 Dui Xue [compare 4.23])

This poem, which starts on a new line but does not state a separate title, is as follows:北雪犯長沙,胡雲冷萬家。 (Northern snow invades Changsha, Hu clouds make ten thousand homes cold.)

隨風且間葉,帶雨不成花。 The snow falls with leaves in the blowing wind, it is accompanied by rain but there are no flowers.

金錯囊從罄,銀壺酒易賒。 Although my gold-decorated wallet is empty, it is easy to buy wine on credit.

無人竭浮蟻,有待至昏鴉。 However, no one will do his for me, I have to wait till the crows of dawn.Note:① Crows fly at dawn, so “至昏鴉” means at dawn.

Goes with image at end.

- 又雪 You Xue: (14.84 Snow Again)

This final poem, which again starts on a new line but does not state a separate title, is as follows,南雪不到地,青崖沾未消。 (Snow in the south doesn’t reach the ground, on the green slope it soaks without melting.)

微微向日薄,脈脈去人遙。 Already inconsequential, as it faces the sun it becomes thinner. From where I silently gaze it seems quite far.

冬熱鴛鴦病,峽深豺虎驕。 The winter is warm and the mandarin ducks look ill; deep in the gorge jackals and tigers gloat.

愁邊有江水,焉得北之朝。 My sadness is accompanied by river's water: when will I be able to return north to the capital?Goes with image at end.

Closing postscript by the calligrapher Jin Cong (5 lines; see below, with translation.)

- Facing the Snow (23.14 對雪 Dui Xue [compare 4.23])

- (Lu Tong:) Song of Tea (茶哥 Cha Ge)

Image at the end of the scroll "Poetic Feelings of Ancient Sages"

This shows Jin Cong's postscript and a view of Du Fu huddling under cover on a small boat, an image appropriate to the final three poems.

|

The three closing poems by Du Fu have only this one image, bringing the number of images to 9 and, as can be seen above, 11 poems. It is thus not clear why the Postscript by Jin Cong says there are "古詩十二首 12 ancient poems".

It is also intended that further commentary will be added here connecting all these poems and illustrations to existing qin melodies. However, I have not as yet studied the images and text of the scroll carefully enough to do so, particularly with regard to the seventh to eleventh poems.

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

1.

Commentary on Poetic Feelings of Ancient Sages (古賢詩意圖 Gu Xian Shi Yi Tu)

3308.xxx.

Much of the detail given here comes from online sources, in particular 360doc.com and

shuge.org.

The typical online commentary that I have found so far gives the following details about the whole scroll:

《古賢詩意圖》

明杜堇紙本墨色縱28釐米橫1079.5釐米北京故宮博物院藏。本幅無款印。共九段,每段有金琮書詩,卷未金琮跋云:

「□□索僕書古詩十二首,將往要杜檉居為圖其事,檉居無訝僕書敢佔其左,以漬痕在耳,他玉圖成必有謂珠玉在側,覺我形穢者,僕奚辭焉。弘治庚申六月廿八日,金琮記事。」

全卷畫幅,杜堇細心體會詩意,作出巧妙構思,人物突出,情景交融。人物用白描法,線條流暢,稍有輕重提按,含蓄秀雅。山石樹木安排簡潔而自然,山石用側鋒斧劈皴,近馬遠、夏圭,但用筆卻縝密透逸,具元人韻致。此圖為其白描巨構佳作。Poetic feelings of Ancient Sages (Tentative translation)

Ming Dynasty Du Jin, ink on paper, 28 cm in height and 1079.5 cm in width, in the collection of the Palace Museum in Beijing.

This scroll has no signature or seal. There are nine sections in total, each with a poem written in calligraphy by Jin Cong (41049.689).

Jin Cong's postscript at the end of the scroll says:"□□ asked me to write (calligraphy for) twelve ancient poems, and was about to ask Du Fuju (Du Jin) to illustrate the matter. Fuju was not surprised that I dared to write on the left, because there were stains on the side (?). Other jade (?) images must have been completed, and they would have felt that my figures were obscure. What could I say? Jin Cong recorded this on the 28th day of the 6th month in the gengshen year of Hongzhi." Throughout the scroll, Du Jin carefully understood the meaning of the poems and made clever ideas, with prominent characters and a fusion of scenes. The figures are drawn in line drawing, with smooth lines and slight weight, making it subtle and elegant. The arrangement of mountains, rocks and trees is simple and natural, and the rocks are drawn with side-edge axe-chopping texture, similar to Ma Yuan and Xia Gui, but the brushwork is dense and free, with the charm of Yuan Dynasty painters. This painting is a masterpiece of his large-scale line drawings.

The "□□" in online copies of this and similar commentary (usually written "金琮跋云□□索僕") is puzzling. As can be seen above by comparing

this text with the right side of this image, it comes just before the quotation of Jin Cong's postscript. Was the "□□" added simply because the opening of the postscript is indented, or does it mean that something (two characters?) were cut out or indecipherable in the original. (All online versions do this without explanation, leaving the suspicion they were just copying each other without trying to understand why).

(Return)

2.

Du Jin 杜堇 (ca. 1465–1509;

Wiki)

See also his Lin Bu in the Moonlight as well as this reproduction of his 梅下橫琴圖 Playing the Qin Underneath a Plum Tree.

(Return)

3.

Jin Cong 金琮 (1449-1501;

Baidu)

Noted calligrapher.

(Return)

4.

Incomplete scroll?

Am I missing one? As yet I have not found a study of this.

(Return)

5.

Youjun and a Caged Goose (右軍籠鵝 Youjun Long E)

I have not yet found a translation.

(Return)

6.

Painting by Chen Hongshou

Reproductions are sold by Rong Bao Zhai. I do not know the location of the original.

The following translation of the poem into modern Chinese was copied from www.27on.com:

流水盤旋繞著千回百轉的山巒,這樣的景象是畫在生綃上的幾幅圖畫,它們被掛在中堂。

武陵守是一位喜歡作畫的人,他將桃源圖題上字,裝上封寄到遠方京城的尚書省南宮中。

南宮先生得到畫卷非常高興,在圖上揮筆題詞,筆勢浩蕩,波浪起伏。

圖畫妙絕傳神,文章精巧工穩,奇異的仙境也恍恍惚惚好像移到了這裡。

畫面上所畫在山谷岩壁,上開鑿建築的房屋,房屋接著房屋,牆接著牆連綿不斷。

秦朝與漢朝的衰敗從來沒有聽說,天開地裂的變化他們也毫不關心。

遠近的地方都種滿了開花的桃樹,盛開的桃花彷彿在川原上蒸騰出燦爛的紅霞。

剛剛來到這裡還思念著故鄉,經過長久的時間後這裡反倒變成了家園。

不知道乘船的漁人來自什麼地方,根據他的不同形象人們紛紛猜測向他打聽。

漁人說起了劉邦斬蛇取代了秦朝,五馬南渡之後如今已是東晉的天下。

聽完漁人的敘述大家都淒然感嘆,自己說遷移到桃源今天已有了六百年的時間。

當年的萬千事件我們都曾親眼見過,不知到今天還有多少在流傳著。

大家都爭著拿出酒食來款待漁人,他們的禮節與器物都與世人大不相同。

漁人在月明之夜獨宿在空空的玉堂中,骨冷魂清感覺到萬念俱消,夢也不做一個。

半夜的時候聽到金雞在啁哳啼叫,太陽出來也讓漁人感到怦然心跳。

在人家他還有家室之累因而不敢在此處逗留太久,最終還是懷著戀戀不捨的惜別之情離開了仙境。

船啓動之後揮槳而進,再要回首仙境時,只看見一片暮色蒼茫的水面。

世上一般人哪能知道桃源究竟是真是假,到如今傳說此事的人也還是那些武陵的居民。

My editing of the Google English version is incomplete.

(Return)

Return to Art Illustrating Guqin Melodies

or to the Guqin ToC.