|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Lixing Yuanya ToC / Tea and guqin | Music and lyrics 首頁 |

| Song of Tea | 茶歌 1 |

| 清徵 Qingzhi mode: 1 2 4 6 5 1 2 changed to 1 2 4 5 6 1 2;2 largely tetratonic (1 2 5 6)3 | Cha Ge |

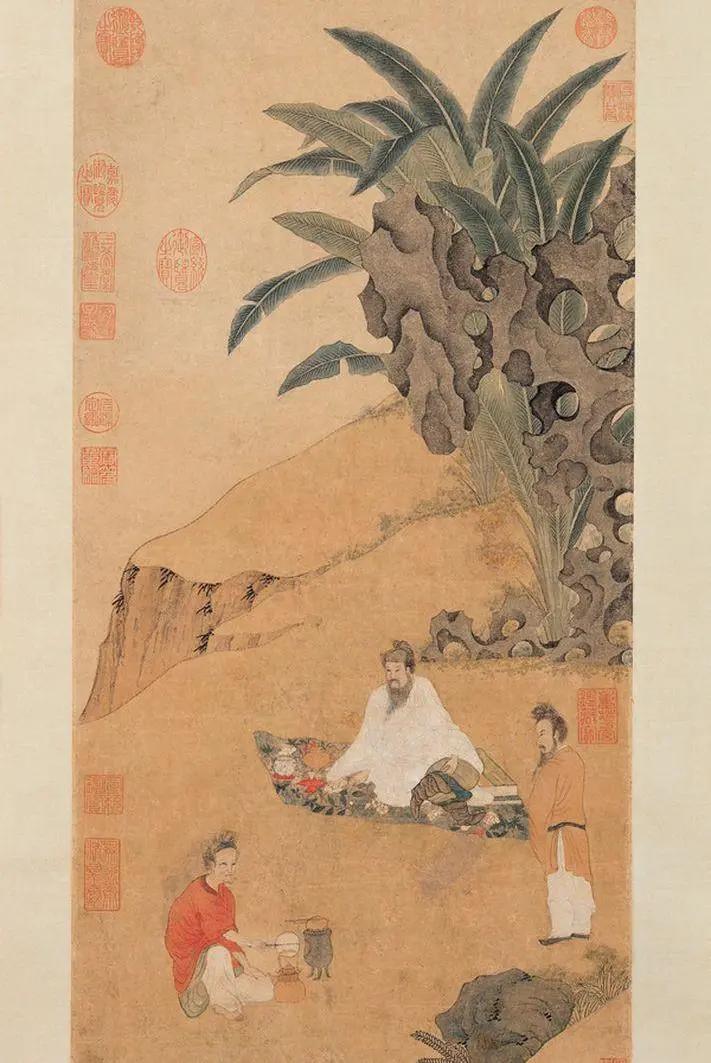

| Lu Tong Making Tea (see full) 4 |

This melody has the feeling of a meditation on the wonders of tea. It comes from a time when only silk strings were to be heard on a guqin. Still today the subtle tones available only from silk strings epitomize the subtle flavors of freshly brewed tea.5

This melody has the feeling of a meditation on the wonders of tea. It comes from a time when only silk strings were to be heard on a guqin. Still today the subtle tones available only from silk strings epitomize the subtle flavors of freshly brewed tea.5

Cha Ge, surviving only in Lixing Yuanya (1618),6 is set to a poem by the Tang dynasty tea lover and poet Lu Tong (790–835),7 depicted at right in a painting attributed to Qian Xuan (1235-1305). Another painting of these same people, shown below, dates from 1617, the year before the present melody was published. A silk string qin would have fit in perfectly in such a setting (see the image here). Metal strings, which did exist in China at that time, would have been unthinkable on a guqin.

The poem, entitled "Written in haste to thank Imperial Censor Meng8 for his gift of freshly picked tea", is particularly well-known through its central section the lyrics of which have long been popular as a separate poem called The Seven Bowls of Tea.9 Many translations have been made of the whole poem, even more of the central section. The one by James A Benn in his Tea in China, p.91, translates the central section as follows:

The second bowl banishes my loneliness and melancholy.

The third bowl penetrates my withered entrails,

finding nothing except five thousand scrolls of writing.

The fourth bowl raises a light perspiration,

as all the inequities I have suffered in my life out are flushed out through my pores.

The fifth bowl purifies my flesh and bones.

The sixth bowl allows me to communicate with immortals.

The seventh bowl I need not drink,

I am only aware of a pure wind rising beneath my two arms.

Although this section of the original poem effectively divides it into three parts, the earliest surviving written copies are not known to have been divided into sections.

Modern copies also are often not divided at all. Others though, including many translations, divide the poem in various ways. For the qin setting here it was divided into four. Elsewhere it can be found divided into three, four or five sections, with the four section versions divided in differing ways.11 The setting itself largely follows the traditional pairing method of one character for each right hand stroke.

Lixing Yuanya does not directly attribute the the melody Cha Ge to anyone. Its preface, presumably by the handbook's compiler Zhang Tingyu, says that it was Lu Tong himself who "created this song",12 adding that it (presumably the melody) has a old style that may be hard to understand. Although this suggests Zhang didn't create the melody himself, it is theoretically possible he created it in a form that he considered ancient. In any case, there is no evidence connecting Lu Tong himself to this melody, or even suggesting one way or another that he had any sort of melody in mind when penning the lyrics.

The tuning and modality of Cha Ge (see qingzhi mode footnote) are both quite strange. Although the tuning calls for lowering the fifth string and raising the fourth, giving 1 2 4 6 5 1 2 for the relative pitches of the seven strings, I have been unable to find the advantage of playing the melody this way rather than using standard tuning, 1 2 4 5 6 1 2. In addition, there is one passage in double stops that seems to have been written using standard tuning. This suggests the melody might originally have been written down using standard tuning, then for unknown reasons was re-arranged for this non-standard tuning without intentionally changing any pitches. For these reasons in my transcription I use standard tuning.13

As for the modality, if the melody was completely tetratonic it would use only four tones (and/or their octaves). Here the relative tuning of 1 2 4 6 5 1 2 was selected so as to avoid most notes that are not in the standard Chinese pentatonic scale, 1 2 3 5 6; see further comment here and here). Considered this way, the melody mostly uses these four of the five notes of the standard pentatonic scale: 1 2 5 6 (do re sol la; see details). However, unlike with all the previous zhi mode melodies I have studied, where the relative note 5 seems to function as the main tonal center and so the relative note 1 is generally avoided because it feels like a fa, here the note 1 (do) is very prominent (57 occurrences) while 7 and 7b (a third up from 5) are almost negligible. In addition, the relative note 4 (fa), while not particularly common (ten occurrences), occurs in prominent places, with the melody ending somewhat strangely on do over fa. Plus there may be some suggestions of microtonal alteration of pitch. All this together gives the melody a modal feel very different from all the other Ming dynasty melodies I have reconstructed, the vast majority of which are in either a standard do-sol or la-mi mode.14

The above discussion mostly concerns the notes (relative pitches) separate from the rhythms/note values. In this regard there are a number of idiosyncrasies in the tablature writing that have helped make this melody quite a challenge to reconstruct, but that may also give further clues to what the original rhythms might have been.15

Cha Ge preface

16

The melody preface says,

Translation tentative; does it suggest Zhang Tingyu copied it from some old manuscript he found?

| Cha Ge music and lyrics (at right: original and my transcription; listen) 17 | Original tablature (.pdf) Transcription (pdf) |

Further regarding the lyrics paired to the 1618 melody, the 1618 lyrics have a few differences from what seems generally to be considered as Lu Tong's original. The text below generally follows this original, with the differences indicated below by "1618 version => original"; my transcription also generally follows the original. As for the division into four sections, this is discussed further below under Structure of the Cha Ge lyrics.

The original lyrics, with my literal translation, are as follows:

The melody itself is discussed above.

1.

Cha Ge 茶歌 (QQJC VIII/285;

31/240/454)

The 1618 Song of Tea, which seems more like a meditation on tea, has proven to be one of the most difficult pieces to reconstruct. The limited variety of notes makes it more challenging to find in it an interesting instrumental melody, while the melodic line is much more angular than melismatic, making it difficult to sing. The extra detail in translation and illustration, but especially in melodic and structural analysis, all document some of the extra effort necessary in reconstructing this melody.

2.

Qingzhi Mode (清徵調 Qingzhi Diao)

(in ToC)

Qingzhi mode appears on at least one old melody list

(1590) and is also used for a melody published in

1677 (臨江仙; XII/380) and another one in

1875 (耕莘釣渭

Geng Shen Diao Wei; standard tuning).

It is not clear why the mode is called qingzhi for any of those other melodies. Here perhaps it is related to the fact that the primary tonal center does seem to be the note and string called "zhi".

The tuning/mode used here actually is unique. Tuning instructions are to "緊四慢五絃各一徽 tighten the 4th and loosen the 5th strings one interval each"; this in effect switches the tuning for the 4th and 5th strings. To explain: qin tablature, as outlined in the illustration here, consists of clusters in which instructions for where and how which finger of the left hand stops a string are at the top, which string and how the right hand plucks a string are at the bottom. Looking at the original tablature, if wherever you see a "four" at the bottom of a cluster you change it to a "five", and wherever you see a "five" at the bottom of a cluster you change it to "four", you end up with exactly the same melody but played in standard tuning. That is what I have done in my transcription.

The reason the strings were switched in this way remains mysterious, but one interesting characteristic can be seen in the tablature paired to the first phrase in Section Three. All notes in that passage are played with the left hand thumb in the fifth position. With the tuning of the fourth and fifth strings reversed the passage can be played comfortably with the thumb across the fifth and sixth strings. With standard tuning it is played on the fourth and sixth strings, giving quite a staccato sound if the strings are stopped only with the left hand thumb. This seems hardly a reason to switch the strings, since the passage can easily be played with the left thumb on the sixth string and the left index finger on the fourth string, but you do need to consider the awkwardness of fingering when trying to determine what the original rhythms and note values might have been.

As for the modal characteristics, the music is largely tetratonic (4 tones; little information is available on this kind of music). Since the relative pitches are not being stated, one must consider at least two possible ways to treat the tuning (my own transcription uses the first):

Before giving details of this, note that in this analysis of the 1 2 4 6 5 1 2 option I have divided Section Three of the melody into three parts: 3, 3A1 and 3A2. This terminology can be used to outline other possible divisions in these ways:

Further regarding Section 3A, beginning the Bowls of Tea song, the opening five-note phrase, in double stops repeated once with lyrics for each of the first two bowls of tea, is quite dramatic and thus seems clearly to start a new section. From a musical standpoint, though, it seems more like a transitional passage between the previous half of the piece, all in harmonics, and the latter half, which is completely in harmonics. Note that the tonal center of Section 3 before here is clearly on 5 and 2, ending with the sequence 6->5->2; Section 3A, the passage with the first two bowls of tea, plays the sequence 6->5->4 twice, clearly changing the tonal center to 4 (fa). Section 3B, continuing on to the third bowl, immediately returns to the sequence 6->5->2. On the switch to harmonics in the next line also seems to be starting a new section.

According to my transcription the melody has 273 notes. Here now are two charts showing detail on the results for each of the two ways to consider the tuning:

As can be seen, 94.2% (258 of 274) of the notes are 1, 2, 5 or 6, though that number goes down to 91.3% if you exclude the 8 (2.9% of the total) that seem intended to be altered in some way that is not completely clear to me (compare the way notes are perhaps microtonally altered here to

these comments on the way notes seem to be microtonally altered in the Chun Xiao Yin from the Songxianguan Qinpu dating from almost the same year [1614]). I generally play the altered notes here just slightly sharp rather than a half tone sharp.) Further regarding these 8 (located in the chart by * and marked with ⬆︎ an upward arrow in my transcription):

As for the other 5.8% (16 notes), they are divided as follows,

Although the melody ends on 1 over 4 (!), and the first line of the

Seven Bowls song has two phrases ending on 4, a calculation of the phrase endings throughout the melody shows that the two main tonal centers and two 5 and 2, as follows (2 means higher octave;

4 means lower octave):

This shows 5 (sol) as the main tonal center in Section 1 while in Section 2 it is mixed between 5 and 1. After the Seven Bowls lyrics begin with 4 as the ending, the phase endings are almost completely on 2 until the last two phrases, which switch the tonal center to 1. In fact, the structure most common in earlier melodies using the standard zhi mode has 5 as the main tonal center with 2 secondary (rarely changing to 2 over an extended period, as here); and they not uncommonly revert to ending on 1 or perhaps 1 over 5, but never 1 over 4.

In this case 258 of the 274 notes are 2, 3, 5 or 6, the other 16 notes being 1 (10 occurrences), 1 sharp (once), 4 (once) and 7 (3 times), with the piece ending on 5 over 1. Here the main tonal center begins as 2, with secondary tonal center as 6 (again reversing in the second half, with 6 becoming primary) and the melody ends on 5 over 1.

A calculation of the phrase endings throughout the melody shows that the two main tonal centers are 2 and 6 (underlining a note considers it as in a lower octave), as follows:

No matter which string is considered as do (1), there is a sudden shift in the tonal center during the last two phrases. If treating the first string as 1, then the penultimate phrase of the melody ends on 1, while the closing note of the whole piece is 1 over 4. If the third string is 1, then the penultimate phrase of the melody ends on 5, while the closing note of the whole piece is 5 over 1. Which of the two is more typical of zhi mode?

Almost all earlier zhi mode melodies end on 5 or 5 over 2

(further comment), the only exception from Shen Qi Mi Pu or

Zheyin Shizi Qinpu being the latter's

Nanxun Ge, which ends 5 over 1. The last two lines of Cha Ge (beginning with "安得 How can...") seem to be changing the tonal center to the relative pitch 1 and thus prepare the ear (certainly the Western ear and from my experience analyzing Ming dynasty melodies quite likely also the Chinese ear, though not necessarily at the end of pieces) for a closing on 1 (whether "resolving" down a fifth from the earlier tonal center on 5 or down a pitch from the earlier tonal center on 2). Thus, ending with 4 and then 4 over 1 gives a much different modal feeling than would ending with an octave on 1.

Complicating any modal analysis, the way the tablature is written makes it difficult to interpret in several places. This is in part because for intermediary positions the finger position indications do not follow the common early Ming standard. For example, the tablature here never follows the common Ming standard of using "七八 between 7 and 8" or "九十 between 9 and 10", instead there is only "上 above". Here two places in particular have problems that stand out:

Also puzzling is that elsewhere in the piece "上" is written into the tablature at the end of notes where there is no reason to think it means "slide up" to something (e.g., see mm.27, 31, 33, 52 and 86 ). I have not seen this sort of tablature indication explained anywhere in earlier handbooks, and other melodies in Lixing Yuanya seem sometimes to use both earlier and/or later ways of indicating such positions. Other late Ming handbooks also seem to have this issue, suggesting this was a transitionary period between the old fingering indication method and the modern decimal one.

3.

Largely tetratonic (1 2 5 6 1)

As discussed in the previous footnote, there is some uncertainty about at least eight of the notes. The fact that a number of notes do not fall within the scale 1 2 5 6 could be considered to mirror the fact that many qin melodies from the Ming dynasty, though largely pentatonic, include more non-pentatonic notes than did later versions of the same melodies. From this it might seem that the old literati instinctively thought of melodies in a pentatonic way, but (unless perhaps they were "fundamentalist" Confucians) they found notes that were outside the pentatonic note collection to be interestingly colorful.

Here is it interesting to compare this melody with the

tetratonic arrangement of

Jiu Kuang that was made for the

bell set in the collection of the Museum of East Asian Art, Cologne. The note availability for the bells, shown

here, is related to the way the bells can produce two pitches a third apart, while the scale for Cha Ge is tetratonic in the above-mentioned Pythagorean way, with non-tetratonic notes brought in for special effect.

To explain this, as the data from these charts shows, although Cha Ge is basically tetratonic, its scale is 1-2-5-6-(1) while that of the Cologne bells is 1-3-5-6-(1). Presumably this is because the Cologne tuning is dependent on bells that do not have the natural Pythagorean relationships. More noticeable, though, is the importance here of the note 4 (fa). For the rest perhaps the apparently altered tones indicated by "上 shang" could be ignored, but the effect of changing the two phrases with fa seems more significant than the effect of changing the notes in the purely tetratonic (but quite catchy) Jiu Kuang adaptation.

As the sun rose late one morning,

an envoy knocked on the door jolting me

from a dream.

(See image below: "An envoy knocked on the door")

口傳諫議送書信,白絹斜封三道印。 (口傳=>口云)

He said imperial censor (Meng) had sent a letter,

it was on white silk and slanting across it were three seals.

開緘宛見諫議面,首閱月團三百片! (首閱=>手閱

Opening the missive, it was as if I could see the imperial censor's face:

he had personally sent me some "full moon" (tea): 300 cakes!

It was known that he had gone during the New Year into the mountains,

when insects were just beginning to be aroused by spring breezes.

天子自嘗陽羨茶,百草不敢先開花。 (自=>須)

The Son of Heaven should (be the first to) taste this Yangxian tea

when all the other plants have not yet dared to bloom.

仁風暗結珠琲瓃,先春抽出黃金芽。 (琲瓃 [pearls of frost]=>蓓蕾 [flower buds])

(But) kindly breezes had dissipated the pearls of frost (on the branches),

at the beginning of spring drawing out the yellow golden buds.

摘鮮焙芳旋封裹,至精至好且不奢。 (焙芳=>焙方)

Picked fresh, (the buds) were dried fragrant and curled up,

(so the tea could be) at its best and not overblown.

至尊之餘合王公,何事便到山人家。

This was supposed to be sent to honor royalty,

what an affair that it had been brought to this home in the mountains.

Myself boil and savor the

tea19

I had closed the gate to my humble abode so that no common folk could intrude,

and with gauze cap strapped on would myself boil and savor (the tea;

see image at right).

碧雲引風吹不斷,白花浮光凝碗面。

The azure clouds drawn by the breeze wafted (their aroma) continuously,

white flowers floating and shimmering on the surface of the bowl.

(The "seven bowls" passage [see above] begins on the next line.)

一碗喉吻潤,二碗破孤悶。

The first bowl does my throat and mouth moisten,

the second bowl breaks my lonely depression.

(From here to the end the melody is played completely in harmonics.)

三碗搜枯腸,唯有 文字五千卷。

The third bowl allows me to search my dried up intestines

where there are only the writings from 5,000 scrolls.

(Intestines? Scrolls?)

四碗發輕汗,平生不平事,盡向毛孔散。

The fourth bowl brings out mild perspiration, (and so)

my whole life's troubling affairs all go through my pores and are dispersed.

五碗肌骨清,六碗通仙靈。

The fifth bowl makes my whole body cleansed,

the sixth bowl sends me off with the immortals.

七碗喫不得 也,唯覺兩腋 習習清風生。

The seventh bowl I can not drink down:

and it just seems as though I have two wings that rustle as a light breeze arises.

Penglai (mountain of immortals), lies at such a place!

I, Yuchuanzi, will mount this light breeze: I want to return there.

(This is the end of the "seven bowls" passage that began

above [comment].)

山上群仙司下土,地位清高隔風雨。

From the mountain all the immortals have come down to earth,

but with a remote purity that separates them from wind and rain.

安得在知百萬億蒼生命,墮巔崖受辛苦。 (堕在巅崖受辛苦=>堕巅崖受辛苦)

How can they know the fates of the countless lives,

of those who fall down beneath the summit and undergo bitterness!

(This is said to refer to the tea pickers' labor.)

便諫議問蒼生,到頭應得蘇息否。 (便為=>便從)

So I must ask the imperial censor whether these lives

in the end will ever be able to rest or not.

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

31686.177 茶歌:採茶時所唱之歌謠 says "tea song: a song sung while picking tea", but the present melody does not have the flavor of what today are likely to be considered as tea picking songs. The closest I have heard to that is a melody called Tea Picker's Melody (採茶調 Cai Cha Diao 12564.xxx; .30 is 採茶歌 Cai Cha Ge (Tea Pickers' Song): 曲牌名 the name of a qupai but NFI). Cai Cha Diao is said to have been arranged by 龔一 Gong Yi from from a "Sichuan folk song" actually called Picking Flowers (四川民歌採花 Cai Hua;

YouTube). In contrast, m.guoqinwang.com compares it with what it says are or were other tea songs, naming 打茶調 Da Cha Diao (only 12054.68 打茶圍), 敬茶 Jing Cha (13621.xxx) and 獻茶調 Xian Cha Diao (21260.xxx). Gong Yi's adaptation (bj-myt.com) was included as a Level 5 melody in the Chinese conservatory syllabus called Guqin Quji

(古琴曲集).

(Return)

18003.674 only 清徵qingzhi:the entry (see

here) mostly concerns the story told here of Shi Kuang demonstrating the powerful emotional effect playing a qingzhi melody could have:

Here is a chart of note occurrences when considering the first string as 1 (3A1 and 3A2 have the special lyrics from here; the last note is a

diad on C over F):

\ Pitch

Section \A

Bb

B

C

Db

D

Eb

E

F

F♯

G

G♯

C/F

Total

1

4

1

9

4

1

6

21*

46

2

7*

14

24*

2

1

28

76

3

4

3

13

10

30

3A1

4

2

4

10

3A2 (harm.)

4

13

19

1

14

51

4 (harm.)

8

18

17

2

15

1

61

Total #

31

1

57

77

3

11

1

92

1

274

%

11.0

0.4

20.8

28.1

1.1

4.0

0.4

33.6

0.4

100%

4,4. 2,2. 2,5,5. 2,2. 5,2.

Here the chart of note occurrences changes to be considered as follows:

\ Pitch

Section \A

Bb

B

C

C#

D

Eb

E

F

F♯

G

G♯

G/C

Total

1

4

1

6

21*

4

1

9

46

2

24*

2

1

28

7*

14

76

3

13

10

4

3

30

3A1

2

4

4

10

3A2 (harm.)

19

1

14

4

13

51

4 (harm.)

17

2

15

8

18

1

61

Total #

77

3

10

1

92

32

1

57

1

274

%

28.1

1.1

4.0

0.4

33.6

11.0

0.4

20.8

0.4

100%

1,1. 6,6. 6,2,2. 6,6. 2,6.

(Return)

What might be called a "natural" tetratonic scale is one comprised of the first four interval in the Pythagorean cycle of fifths (Chinese:

sanfen sunyi): 1 -> 5 -> 2 -> 6 (The standard pentatonic scale adds the fifth note in this cycle: 3 to make it pentatonic.) Brought down so that all notes are in the same octave gives 1 2 5 6 (then 3). This is a scale apparently known to have been used in some ancient cultures. (From Wikipedia

tetratonic scale it is not clear how many of these are Pythagorean). How a largely tetratonic scale came to dominate the present melody is not clear.

(Return)

| 4. 盧仝烹茶圖 Lu Tong cooking tea, by 錢選 Qian Xuan (1235-1305) | By 丁雲鵬 Ding Yunpeng? |

In addition to the one above by Qian Xuan, a number of well-known paintings show people drinking tea. One of the most famous is 品茶圖 Tasting Tea by 文徵明

Wen Zhengming (1470-1559;

this copy is said to be in the Palace Museum, Taipei, but see here). Another, shown below, is part of a scroll by 杜堇 Du Jin.

In addition to the one above by Qian Xuan, a number of well-known paintings show people drinking tea. One of the most famous is 品茶圖 Tasting Tea by 文徵明

Wen Zhengming (1470-1559;

this copy is said to be in the Palace Museum, Taipei, but see here). Another, shown below, is part of a scroll by 杜堇 Du Jin.

Yet another is the one shown at right, by 丁雲鵬 Ding Yunpeng (1547-1628; Wiki). Dated 1617, the year before the melody Cha Ge was published in Lixing Yuanya, it re-configures what looks like the same three people from the image at top. On the top of the painting itself is an inscription attributed to the Qian Long emperor and dated 1784 that says,

Elsewhere there seems to be information saying the original of the painting is in the Palace Museum, Beijing.

As for the painting by Qian Xuan (Wiki), the original is in the Palace Museum in Taiwan. There are comments about it at digitalarchive.npm.gov.tw and theme.npm.edu.tw, but this actual pdf of the painting was downloaded from elsewhere. Note that the inscription at the top (not yet translated) is actually dated 乾隆乙已 Qianlong yiji year: 1785. The reason for this is not yet clear to me.

Of this painting, John Blofeld wrote in The Chinese Art of Tea, p.14,

Less fanciful is this comment, translated from another online image found in several places on the internet such as www.moyuanzhaiwenhua.com, where there is also a copy of the complete scroll):

Qian Xuan was apparently noted for his paintings of recluses.

| The image at right is the fifth entry from a scroll by 杜堇 Du Jin. | "An envoy knocked on the door" |

It directly connects to a line in the poem above.

It directly connects to a line in the poem above.

More paintings that show qin and tea together are listed

here under "Guqin and Tea", but those are not connected to Lu Tong.

(Return)

5.

Silk strings and tea

To some ears, playing qin with the modern non-silk strings is like drinking instant tea: it is convenient, but the subtle flavors simply are not there.

This is further discussed here.

Also, saying that "this melody has the feeling of a meditation on the wonders of tea" might perhaps be seen as a comment on the fact that metal strings were imposed on qin players during the Cultural Revolution as part of an effort to make the qin serve the people, not be an instrument of self-cultivation. Both aims are laudable but should not be seen as mutually exclusive. This is also further discussed here.

One might point out that playing a silk string qin in nature can be hard on the strings because of matters such as changes in temperature and humidity, and that the sounds of nature may serve to hide the subtle coloring from silk strings: in such an environment would not metal or composite strings be better, or at least just as good?

Unfortunately this was never discussed in the traditional writings: players simply went on playing with silk strings wherever they were.

(Return)

6.

Trace Cha Ge

Zha Guide 31/240/454 lists it only here.

(Return)

7.

Lu Tong 盧仝 (790–835)

Lu Tong (Bio/381, Wiki and ICTCL p.954), self-nicknamed 玉川子 Yuchuanzi (Master of the Jade Spring), was from 濟源 Jiyuan (in southern Shanxi). He was a poet best known for his love of travel and especially tea: he spent his life studying it, never becoming an official. Poems in the Complete Tang Poems that are attributed to him and mention qin are included

here.

One of Lu Tong's poems that prominently mentions the qin begins as follows (see original):

Qin players are like the qins on their knees,

Qin listeners are like the strings still in a box.

If the two objects are each in their own place,

how can sounds be transmitted?

The stillness of wind and the essence of air have related feelings,

myriad types of sad feelings become entwined.

At first, beyond Tianshan mountains white snow flies,

then gradually from springs at 10,000 foot heights streams flow.

Breezes cause plum blossoms to fall and lightly flutter,

the fingers are all clean as the sound flows lazily.

Zhao Jun was sadly married to a

nomad prince....

Translation incomplete; it does not mention tea.

(Return)

8.

孟簡 Meng Jian

7107.326 孟簡 Meng Jian says he was 善詩 a good poet as well as an official, but he is generally better known as a tea lover than as a poet. The poem refers to him by rank, Imperial Censor Meng (孟諫議 Meng Jianyi). Hucker translates the rank, "諫議大夫 jianyi daifu", as "Grand Master of Remonstrance".

(Return)

9.

The Seven Bowls of Tea (七碗茶詩 Qi Wan Cha Shi)

Within Lu Tong's poem, set here to music, the section from "一碗喉吻潤" to "唯覺兩腋習習清風生" (not always including "蓬來山,在何處,玉川子,乘此清風欲歸去") is what is called "Seven Bowls of Tea". At present an internet search for this translation of the first line, "The first cup caresses my dry lips and throat", turns up many websites having various versions of this translation (see, for example, "www.westernimmortaltea.com"), but they rarely identify the translator.

The translation in under Lu Tong in

Wiki, attributed to Steven R. Jones (not Stephen Jones) also begins the same ("The first bowl moistens my lips and throat...") then has differences. Most of these translations, if they include the Chinese, usually change the last phrase so that it ends 蓬來山在何處,玉川子, 地位清高隔風雨, but they also tend not to translate the part after 蓬來山在何處.

(Return)

11.

Division into four sections

How this sectioning was decided on for the qin version made is not clear: was it done separately from this melody or specifically for it? This sectioning is discussed further below under Structure of the Cha Ge lyrics.

(Return)

12.

Creator of the melody

Although the preface (q.v.) has Lu Tong "作此歌 creating this song" (not "this poem" or "this melody"), Zha Fuxi's Guide page 31 assigns it to Zhang Tingyu himself. However, the Guide similarly attributes almost all the melodies in Lixing Yuanya to Zhang

(details), and presumably it simply means that Zha thought that Zhang was responsible for the version as written in the handbook. There is no information one way or the other as to whether Zhang based the melody on an earlier qin melody, or on an earlier musical setting of the lyrics in any genre. In any case, although no related melody for any instrument is known to exist, it would be interesting to know whether there is any Chinese tradition of quadratonic work songs. In this regard, though, the melody seems more like a meditation on tea than on a work song.

(An internet search for "Chinese Work Songs" is complicated by the fact that in 2000 the American rock band Little Feat made an album of that name.)

-->

(Return)

13.

Adjusting to use standard tuning

As can be seen by comparing the

transcription to the

original tablature, this is done without changing the melody at all simply by leaving the qin in standard tuning and, wherever the tablature indicates fourth string, change it to fifth string; likewise, wherever it says fifth string change it to fourth. You leave the indicated finger positions as is: the positions indicated as played on the fifth string will now be played on the fourth string and vice versa.

There are several reasons to think the melody might originally have been written down using standard tuning, then (for unknown reasons) was revised to use this unique "clear zhi" tuning.

I know of no other melody that reverses the order of some strings.

14.

Cha Ge melody modal details

15.

Possible rhythmic clues to working out a melody from the Cha Ge tablature

(Return)

See Modality in early Ming qin tablature and also the Qingzhi mode introduction above. It should also be mentioned that I have not studied enough of the melodies in

Lixing Yuanya (or others from that period or later) to know for certain whether the modality here is truly unique.

(Return)

Guqin tablature is written in "clusters", as explained

here. As explained there, the tablature is written largely in shorthand clusters in which the top part tells how and in what position the left hand should stop a string while the bottom part tells which string and how to pluck it.

My focus has in general been on earlier handbooks, where some aspects of the tablature are different not only from what they are today but also from how they were written at the end of the Ming dynasty. Perhaps a deeper study of handbooks surviving from the 17th century will help with some of the problems here. Meanwhile, here are some of the idiosyncrasies one finds in the present tablature, and how this might affect note values:

See also "Complicating modal analysis".

In any case, I interpret it as a reminder not to rush on to the next section.

(Return)

16.

Cha Ge preface

The Chinese original is:

孟簡 孟諫義簡惠茶,謝之而作此歌。奇峭驚人。快人應得稱其古怪云。

(Return)

17.

Cha Ge music

Although I have made a recording and related transcription (see also the original tablature), I do not yet feel I have a real sense of its musical aims. My interpretation has already changed several times as I have continued with my analysis of the structure. Considering the popularity of the associating qin with tea, the apparentl lack of any other recordings of this melody suggests to me that others have also found the music of this tablature difficult to interpret.

See in particular my comments here and at the top of the transcription regarding the string-switching.

(Return)

18.

Cha Ge lyrics and their structure

It is not clear who did the various modifications to the Cha Ge lyrics, including those in Lixing Yuanya. The original title of the poem is 盧仝:走筆謝孟諫議寄新茶 Lu Tong, Rapidly penned to thank Imperial Censor Meng for sending some new (freshly picked) tea.

Further references in the lyrics include these:

- 日高丈五 "As the sun rose late". Regarding 丈五 (zhang 5), would this mean 5 zhang or 1.5 zhang, since Chinese measurements generally worked on a decimal system? (Traditional Chinese measurements were very complicated but often it is said that 10寸 cun = 1尺 chi; 10 chi = 1丈 zhang, comparing a 尺 chi roughly to a foot.) So when 16.12 says 丈六 zhang liu means "一丈六尺 one zhang six chi" and this is "佛的化身 the height of an incarnation of the Buddha", it might seem to be suggesting that was a height of about 10+6 feet and thus that Lu Tong was saying the sun had risen at 一丈五尺, i.e., one chi less than the height of an incarnation of the Buddha. On the other hand, a 丈 can also be a 仗 staff: could 日高丈五 mean the sun looked to have risen a bit higher than his staff?

At the same time, 5/547 is the Chinese idiom “日高三丈" meaning "犹日上三竿 as if the sun were at three o'clock", but the references it gives begin with 湯顯祖 Tang Zianzu (1550 – 1616), i.e. much later than Lu Tong. Was this a literary reference, with Tang suggesting that the person got up even later than Lu Tong had?

Although none of this is conclusive in explaining exactly when Lu Tong says he got up, it seems most likely that he meant that it was rather late. - "周公 Zhou Gong", also in line 1, as explained at 3/295#3 is "喻夜夢 a metaphor for dreaming".

- 陽羨茶 Yangxian is an old name for 義興, now 宜興 Yixing (Wiki), still famous for its tea. Yangxian tea was sent annually to the emperor as a 貢茶 tribute tea.

- 五千卷 Intestines? 5,000 scrolls?: 262.66 五千 does not seem to suggest any special meaning for that number. The idea of scrolls in the intestines is also not clear.

Structure of the Cha Ge lyrics

The structure of the original poem, with its lyrics arranged as 19 lines for the four sections of the 1618 qin song, is as follows

(my transcription has its 19 lines of staff notation lined up accordingly):

- (7+7) x 3.

- (7+7) x 5

- (7+7) x 2

(5 + 5) ("Seven Bowls of Tea" begins with this line)

(5 + [2 + 5]) (Harmonics begin with this line)

(5 + 5 + 5)

(5 + 5)

(6 + 9) - ([3 + 3] + [3 + 7]) (These two rhyme with the last three lines.)

(7+7)

([2 + 7] + 7) (see above)

(7+7)

The earliest surviving copies of the poem apparently had no sectioning, but sectioning is important in trying to understand what musical structure would be most appropriate in setting a poem for guqin. As an example, one might assume that while there may be a pause at the end of a line, there will probably be a longer, or at least more distinctive, pause at the end of a section. More specifically, because an important question is how the division of a melody based on the structure of the lyrics might affect its memorability, this is a very important factor for me when doing a reconstruction (dapu).

The translation by Steven D. Owyoung at chadao.blogspot.com begins, "The sun is high as a ten-foot measure and five; I am deep asleep...". Dr. Owyoung does not divide the poem into sections but he has extensive commentary on the significance of the poem.

Dr. Owyoung also has an online journal, tsiosophy.com ("tsai-osophy" means wisdom of tea).

The translation by James A. Benn in pp.90-92, begins very similarly to that of Owyoung (whom he credits), but he sections the melody as in Lixing Yuanya except that in his version the third section begins not at line 9 but at line 11, the beginning of the Seven Bowls section ("The first bowl.....").

For a division into five sections there is the translation by John Blofeld in The Chinese Art of Tea. His translation begins, "I was lying lost in slumber as the morning sun climbed high...". In his commentary, pp.13-14, he says that he "arbitrarily divided the poem into five numbered sections for convenience in explaining points that might be obscure." Whereas Benn divided the part before the Seven Bowls section into two parts of 3 + 7 lines, Blofield divides it into three parts of 5 + 3 + 1, apparently omitting the 10th line. This makes the Seven Bowls of Tea passage into the fourth section, the present fourth section becoming its section five.

"Here my personal feeling from the music originally made me try to arrange the first two sections as 4 + 4 + 2 lines. However, closer analysis of the music shows that it is at line 4 (the beginning of section 2) that the melody becomes more purely tetratonic. In addition, the slide at the end of line 8 seems to be a section ending, so my feeling for sectioning makes my reconstruction seem to have five sections divided as follows: 3 + 5 + 2 + 5 + 4.

19.

"Myself boil and savor (the tea)": image by 朱元虎 Zhu Yuanhu, 2024

(Return)

Zhu Yuanhu has kindly helped with translation in several places on this website. As of 2024 he is a graduate student at Peking University.

(Return)

Return to Performance Themes

or the Guqin ToC