|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

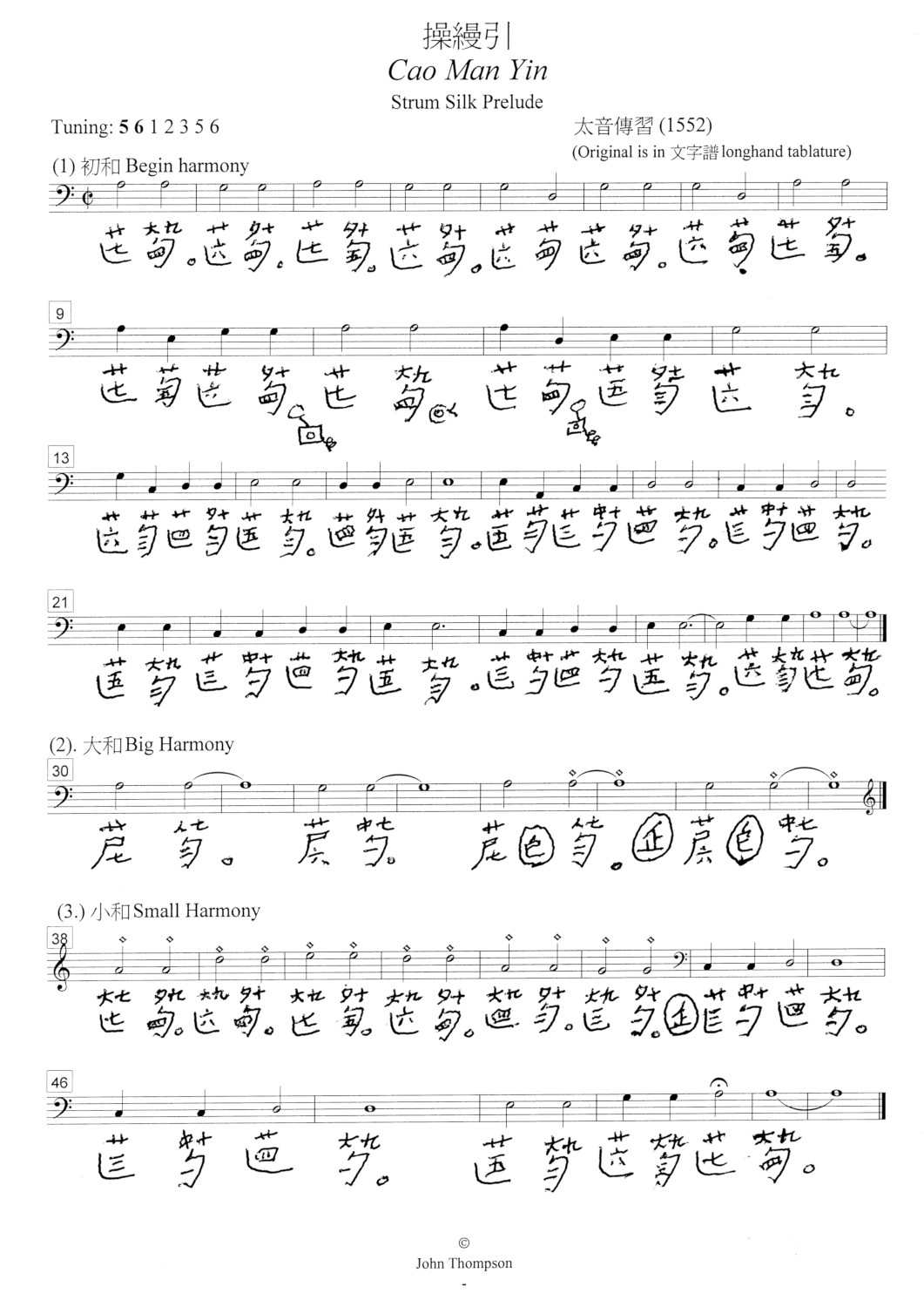

| Teaching HIP / Learning to play qin / Xianweng Cao transcription / 1585 Cao Man Yin transcription / pdf of all three | 首頁 |

| Transcription of 1552 Caoman Yin | 操縵引琴譜、五線譜 |

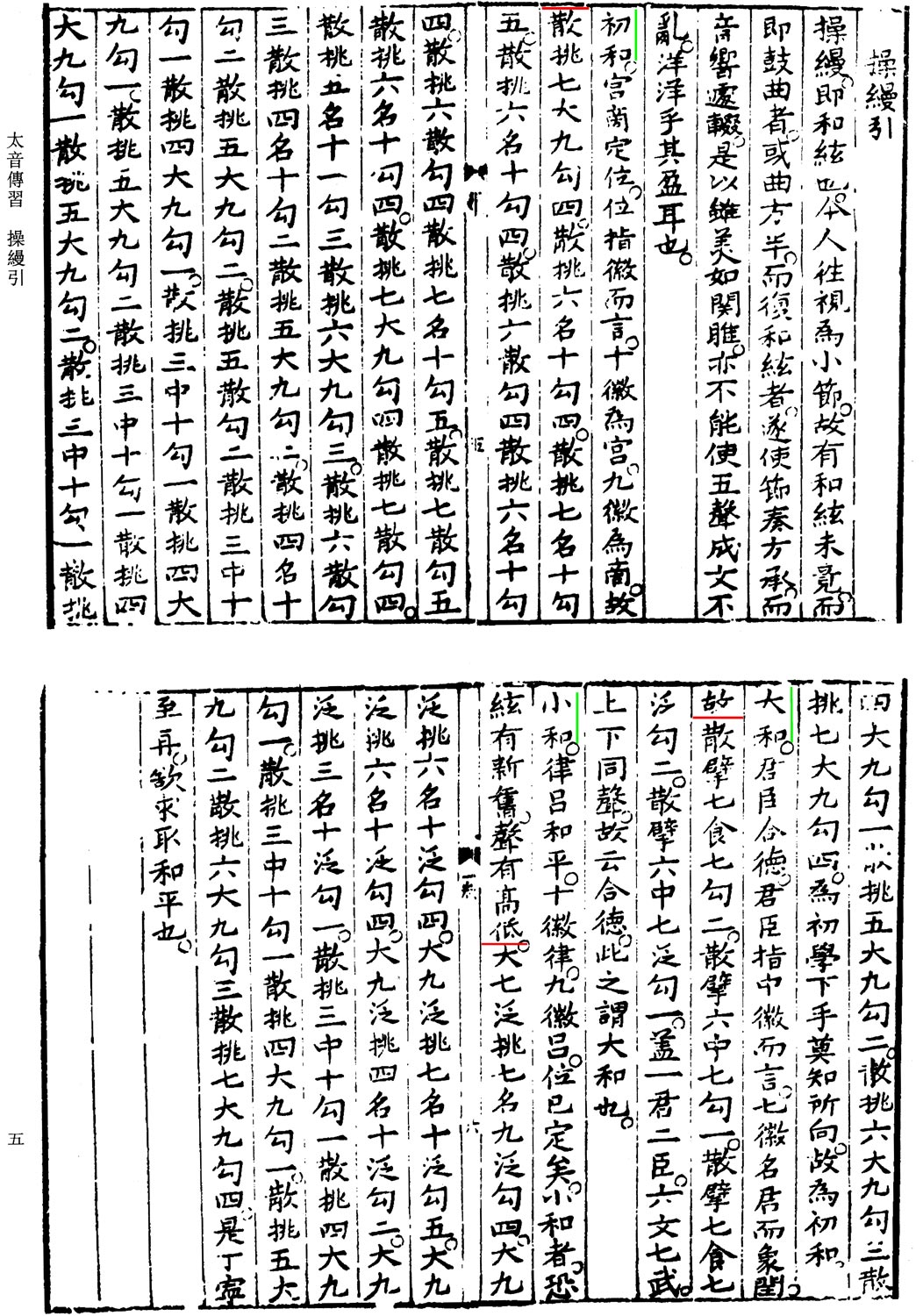

| Green: section titles; red: music begins |

This melody was written out in longhand tablature, the first example of this to have survived since the

You Lan melody from the 7th century or earlier.1 Historical records, and/or perhaps legends, speak of long hand tablature being invented by Yongmen Zhou during the Warring States Period, and then Cao Rou inventing the shorthand form during the Tang. What inspired its use here is unknown. One might speculate that it was done to imply great antiquity to the melody, but more likely it was simply a way of explaining to new students the reasoning behind the shorthand tablature then (and now with only a few changes) in common use.

This melody was written out in longhand tablature, the first example of this to have survived since the

You Lan melody from the 7th century or earlier.1 Historical records, and/or perhaps legends, speak of long hand tablature being invented by Yongmen Zhou during the Warring States Period, and then Cao Rou inventing the shorthand form during the Tang. What inspired its use here is unknown. One might speculate that it was done to imply great antiquity to the melody, but more likely it was simply a way of explaining to new students the reasoning behind the shorthand tablature then (and now with only a few changes) in common use.

As for its age, there is no evidence that it was copied from an ancient source, and the You Lan tablature itself is an unlikely inspiration as the surviving scroll was unknown in China for over 1,000 years after its first appearance in Japan. The only other examples after this seem to have been later versions of Cao Man Yin

- In the transcription (see also below), circled tablatures/punctuation symbols were added; boxed ones were deleted.2

- The tablature has a preface then short comments at the beginning and end of each section.3 Here is a translation:4

- 操縵引 Cao Man Yin

- 初和:宮商定位。位指徽而言。十徽為宮,九徽為商,故:

Initial Harmonizing: (Establishes gong and shang; position is indicated in reference to the huī markers. If the 10th hui is gong, then the 9th hui will be shang. Thus.... (here is the tablature):散挑七,大九勾四。散挑六,名十勾四。散挑七,名十勾五。散挑六,名十勾四。散挑六,散勾四,散挑六,名勾四。散挑六,散勾四,散挑七,名十勾五。

散挑七,散勾五,散挑六,名十勾四【,】散挑七,大九勾四【。】散挑七,散勾四,散挑五,名十一勾三,散挑六,大九勾三。

散挑六,散勾三,散挑四,名十勾二,散挑五,大九勾二。散挑四,名十勾二,散挑五,大九勾二。挑五,散勾二,散挑三,中十勾一,散挑四,大九勾一。

散挑五,大九勾二,散挑三,中十勾一,散挑四,大九勾一,散挑五,大九勾二。散挑六,大九勾三,散挑七,大九勾四。為初學下手莫知所向,故為初和。

This is for beginners who may not know where to begin; hence this section (utilizing only the central hui) is called 'Initial Harmonizing'." - 大和:君臣合德。君臣指中徽而言,七徽名君而象閠。故:

Great Harmonizing: Ruler (first string) and Minister (second string) unite in virtue. 'Ruler and Ministers' refers to the central huī markers: the 7th huī is called ‘Ruler’ and symbolizes centrality. Thus.... (here is the tablature):蓋一君二臣,六文七武,上下同聲。故云合德。此之謂大和也。

So the first (string) is the ruler, the second is minister (going to) the sixth as Civil Lord and seventh as Military Lord; whether higher or lower (octave?) it is the same sound. Thus what is here is called "uniting in virtue". This is what is called ‘Great Harmony’. - 小和:律呂和平,十徽律,九徽呂;位已定矣。小和者,恐絃有新舊,聲有高低。

Small harmonizing: "The lǜ and lǚ are in harmony, with the 10th huī being the former lǜ and the 9th huī being the latter lǚ (?); positions are already fixed. As for "small harmonizing", because strings may be new or old, pitches may be higher or lower (i.e., change in tuning?). Thus.... (here is the tablature):大七泛挑七,名九泛勾四。大九泛挑六,名十泛勾四。大九泛挑七,名十泛勾五。大九泛挑六,名十泛勾四。

大九泛挑四,名十泛勾二。大九泛挑三,名十泛勾一。散挑三,中十勾一,散挑四,大九勾一。

散挑三,中十勾一。三挑四,大九勾一。散挑五,大九勾二,散挑六,大九勾三。散挑七,大九勾四。是丁寧至再。欲求取和平。

This must be practiced repeatedly and internalized if you seek perfect equilibrium."

操縵即和絃也。今人往視為小節。故有和絃未竟,而即鼓曲者,或曲方半,而復和絃者,遂使節奏方承,而音響遽輟。是以雖美如「關雎」,亦不能使五聲成文不亂。洋洋乎其盈耳也。 (Note: 洋洋 instead of 詳.)

"Cao Man" is actually Harmonizing the Strings (i.e., tuning the strings). Nowadays people regard this as a minor detail. As a result they may begin playing before their string harmonization is not as good as it should be, or as they play a melody, perhaps they get halfway through, and they have to go back to harmonizing the strings. Thereupon they cause the rhythms to be abruptly disconnected, and the musical flow suddenly to stop. Then even if it is a piece as beautiful as Guan Ju, they cannot cause the five tones to become elegant and not disorganized, or have a resonant fullness (洋洋乎) fill the ears.

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

1.

Longhand Tablature (文字譜

wenzipu)

Given the singularity of its use here it is rather strange that there is no comment anywhere about this.

(Return)

2.

Comments on the tablature

As for changes in the tablature, in the 1552 Cao Man Yin transcription this only occurs in line two. The reasons for the punctuation change is pretty clear: this balances the phrasing on that line in a very clear and symmetical way that also fits in with the rest of the melody; of course the apparent logic of this change does not prove it is correct, but it does mean I couldn't enjoy playing the line the way it was originally punctuated into three parts.

Further comment:

- The tuning is given as 5 6 1 2 3 5 6 (so la do re mi so la). This means the melody is purely pentatonic; the tonal center seems clearly to be la, giving it a minor mode feel to a Western ear.

- In the typed version there is a comma at the end of each note, unless the note ends a phrase, in which case there is a full stop (circle).

- In the pdf of the original, linked at top, full stops mark the end of phrases.

- Also in that pdf version, the title of each section has a green line marking the title of each section, then a red line where the actual tablature begins.

- Here is an explanation of shorthand tablature by writing it out in longhand forms .

(Return)

3.

Comments at the beginning and end of each section of the tablature

Compare this typed version with the one dated

1559.

(Return)

4.

Comments on the translation

Translation of this section is problematic. The music of this section (see transcription) uses the 9th and 10th positions quite a lot, to a great extent playing the same note first at one hui then on another string at the other hui. However, the first section does the same thing.

(Return)

Return to the Guqin ToC