|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Zheyin ToC Compare Guan Ju Qu (1511) / Themes: Confucian / Birds | 聽錄音 My recording with transcription / 首頁 |

|

01. Cry of the Ospreys

- Zhi mode, standard tuning: 2 1 2 4 5 6 1 2 (modal prelude also has lyrics3) |

關雎

1

Guan Ju An osprey 4 |

Guan Qu is the first melody in the handbook Zheyin Shizi Qinpu

(>1505) that is not identical to a melody in Shen Qi Mi Pu (1425).5 For this reason it is also the first melody on my CD Music Beyond Sound, which consists of recordings of my reconstructions of the 13 melodies in Zheyin Shizi Qinpu that were not in, or not exactly the same as those in, Shen Qi Mi Pu.

Guan Qu is the first melody in the handbook Zheyin Shizi Qinpu

(>1505) that is not identical to a melody in Shen Qi Mi Pu (1425).5 For this reason it is also the first melody on my CD Music Beyond Sound, which consists of recordings of my reconstructions of the 13 melodies in Zheyin Shizi Qinpu that were not in, or not exactly the same as those in, Shen Qi Mi Pu.

Although Zheyin Shizi Qinpu added lyrics to all its melodies, and did so following the rather strict traditional pairing formula (further comment), it seems unlikely that they were intended actually to be sung (on this see further comment below). At the same time, it does seem likely that the words and tablature were paired in a way that helps indicate what the original rhythms of the melody might have been. Thus the precise pairing was certainly a major guideline for my own reconstruction.

Furthermore, although the title of this melody is the title of the first poem in the over 2,500 year-old Book of Songs (Shi Jing), here the lyrics do not form a love song, as did the original Guan Ju lyrics. Instead the lyrics here are combined with political commentary on the affairs of the Zhou dynasty.6

In this way the present Guan Ju stands in contrast to the melodically related but textually different Guan Ju Qu published around the same time in Taigu Yiyin (1511). That version actually sets to music not just Guan Ju itself but also the entirety of the next four poems, word for word (see in 1511). In >1505 there is instead mention of such historical figures as Shao7, and the real focus is on such matters as how the marriage of Wen Wang and his queen symbolize the harmony of society under his rule.8 Note, however, that here Section Six does directly quote from the Guan Ju as in the Shi Jing, and it sets this section apart by putting it in harmonics. However, it only includes the lyrics of two of the five stanzas that comprise the original poem (stanzas 1 and 3).

These original Shi Jing lyrics included in the present version of Guan Ju are thus only as follows:9

"Guan, guan," trill the ospreys,

On the island in the creek.

Modest is the gentle beauty,

Fine for the gentleman to seek.

3

He seeks but cannot get her,

he thinks of her day and night.

Tossing and turning in his plight. (why not "Alas! Alas!"?)

Tossing and turning in his plight.

Other than these four-character phrases in Section 6, the lyrics of >1505 basically consist of phrases of irregular length.

It was common within the qin tradition to suggest that this was one of the most ancient melodies: here and elsewhere it specifically states under the title that 周公作 Zhou Gong ("the duke of Zhou") created it. Zhou Gong was a son of Wen Wang and a younger brother of Wu Wang, the first ruler of the Zhou dynasty (1122-255). However, this title does not seem to appear on early qin melody lists, and it is not at all clear from where the melody came when it started appearing in qin handbooks around 1500.

During the rest of the Ming and throughout the Qing dynasty Guan Ju was one of the most popular of all qin pieces, found in at least 54 handbooks from >1505 to 1894.11 Of these, the 1511 version may actually have been intended for singing. And later ones perhaps added lyrics simply because these two earliest known tablatures had them. Another possibility is that lyrics were included because of an old attitude that said, "if you play then you must sing it".

On the other hand, most surviving Guan Ju tablature is for a purely instrumental piece, with only about 10 (including the first four) having lyrics and only two seeming to have the complete original Shi Jing lyrics. Most of the lyrics are variants on the lyrics used here.12 The aim of the lyrics seems intended to edify the player about the significance of the poem and perhaps also give clues to the rhythm of the melody.

In line with this, in my attempt to reconsruct what might have been the original melody I tried to pay attention to the way someone might have read or recited the lyrics. In general the lyrics in this handbook are not considered to be of a very high standard. In addition, actually singing them seems quite awkward. However, it was interesting to me to keep them in mind while I was reconstructing the piece: the music does seem to enhance the value of the lyrics. In this light, it could be interesting for someone else to recite them while listening to the melody being played. That this was at least sometimes done is evidenced by some published later criticism of such a practice. In contrast, versions such as this one from 1722 relate how the music itself can be sufficient to express the significance of the theme.

The last of the traditional handbooks to include a version of Guan Ju was dated 1894. Thus, any version heard today will be one not passed on through lineal descent but through a modern reconstruction from old tablature, such as my own versions from here (on CD) and from 1511.

The Beyond-Sounds Immortal says,

Ah! His happiness - could anything be so great!

Music (聽錄音 listen with

my revised transcription; timings below follow the recording on my CD)

In addition I have made a video that adds, as a prelude, Section 1 of the 1511 Guan Ju Qu

Nine titled sections (all the lyrics are below with a translation 見中文、英文歌詞);

See also this transcription without the tablature:14

00.00 1. The prince-like osprey finds a good marriage

01.06 2. Very gentle are (the wives of the royal family of) Zhou and Shao

02.09 3. Using (a birdcall) as a metaphor for (the queen's virtue)

02.40 4. Praise (her) virtue and acclaim (her) conduct

03.26 5. (Like) the wind (, the queen) guides the world

04.00 6. They mutually call out in harmony to each other

(harmonics; sing stanzas 1 and 3)

04.19 7. The correct (wedding) ceremony (leads to) a successful marriage

05.19 8. (The king and queen's) virtue (is) as great as heaven and earth

05.59 9. (The king and queen have) eternal worship in the Zhou family temple

06.37 "Sound begins ending" (? Play closing harmonics)

06.54 End

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

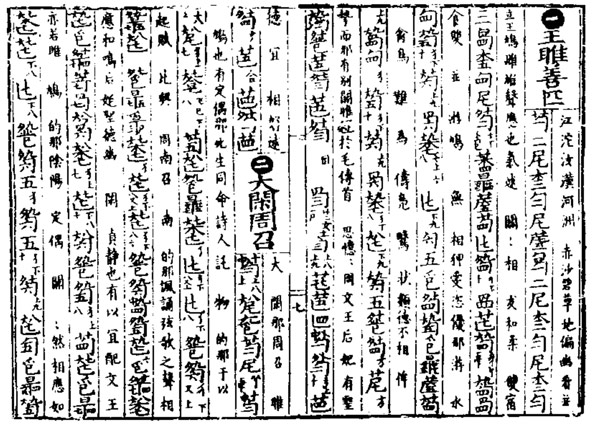

| 1. Guan Ju references | 三才圖會 Sancai Tuhui image: 雎鳩 Jujiu |

What exactly was the bird featured in this melody? With classical Chinese it is often difficult to be certain how to translate the names of plants and animals. This footnote, for example, questions whether the "lan" of the famous melody You Lan ("Secluded Orchid") might actually have been a magnolia rather than an orchid. Similarly with the title of the present melody (as of the first poem in the Book of Songs): Cry of the Osprey (關雎 Guan Ju). The opening lyrics, "關關雎鳩 Guan guan ju jiu", are commonly understood as meaning, "'Guan guan' (cry out the) ospreys." In line with this, 42402.191 關雎 Guan Ju begins by saying guanju is the name of a bird, same as 魚鷹 yuying (fish hawk, etc.; reference: 王銍,默記 Record of Silence by Wang Zhi [Song dynasty, i.e., rather late]). Next it identifies Guan Ju as the name of a Shi Jing poem, referencing the story and poem. The entire entry makes no mention of 雎鳩 jujiu, but then the entire poem does not use "關雎 guanju" in such a way that it cannot be interpreted simply as the title of the poem.

What exactly was the bird featured in this melody? With classical Chinese it is often difficult to be certain how to translate the names of plants and animals. This footnote, for example, questions whether the "lan" of the famous melody You Lan ("Secluded Orchid") might actually have been a magnolia rather than an orchid. Similarly with the title of the present melody (as of the first poem in the Book of Songs): Cry of the Osprey (關雎 Guan Ju). The opening lyrics, "關關雎鳩 Guan guan ju jiu", are commonly understood as meaning, "'Guan guan' (cry out the) ospreys." In line with this, 42402.191 關雎 Guan Ju begins by saying guanju is the name of a bird, same as 魚鷹 yuying (fish hawk, etc.; reference: 王銍,默記 Record of Silence by Wang Zhi [Song dynasty, i.e., rather late]). Next it identifies Guan Ju as the name of a Shi Jing poem, referencing the story and poem. The entire entry makes no mention of 雎鳩 jujiu, but then the entire poem does not use "關雎 guanju" in such a way that it cannot be interpreted simply as the title of the poem.

However, 42932.2 雎鳩 jujiu has the image at right, which looks like a duck, but then says it is the same as 42932.2 鴡鳩 jujiu, which describes it as "雕類 diaolei, a type of fish hawk. To add to the confusion, there is this suggestion that the bird in question should be a mallard because of the sound it makes. And when reading the contrasting opinion below note that mallards are also said sometimes to mate for life. In this regard the modern name for the "oriental turtle dove" (Wiki) is 山斑鸠 shan ban jiu (see also ; see also 斑鸠 Streptopelia), even better known to mate for life.

As for the illustration at top, its text says only that 傳雎鳩,王雎也 "traditional commentary has it that jujiu are the same as wangju. This is commonly translated as wang ju: "princely osprey". However, 21295.1491 王雎 wang ju says things like 雕類 diaolei (water birds), same as 王鴡 wangju and see 王鳩 wangjiu (21295.1848) and 一名雎鳩 also called jujiu. References are again to the Shi Jing, which suggests one can still argue about what type of bird it was to which the poem refers.

Note also that, although the Shi Jing

lyrics have elsewhere been set to qin melodies, including in Guan Ju Qu, these dictionary entries make no mention qin or music.

(Return)

2. 徵調 Zhi Mode

(see also the related modal prelude and its

lyrics

[translated"])

Standard tuning is considered here as 1 2 4 5 6 1 2. The main tonal center based on phrase endings is the relative pitch sol, called 徵 zhi in the corresponding traditional Chinese system and transcribed as G on a piano. This also makes the tonal center the equivalent pitch of the open fourth string, called the 徵 zhi string in the Chinese system. The secondary tonal center is, as usual in traditional guqin music, a fifth above the primary tonal canter: this is the relative pitch re (Chinese 商 shang), written in my transcription as if it were D on a piano.

Except for in Section 7 the note re is by far and away the most common. However, it is not considered the primary tonal center because phrases and particularly sections more commonly end on G.

With the relative tuning considered as 1 2 4 5 6 1 2, the accompanying transcription treats the open first string as C on a standard keyboard though the actual pitch on my recording is closer to Bb or even A. The primary tonal center is then written as G and the secondary tonal center D, the equivalent of the open second string.

For more information about zhi mode see Shenpin Zhi Yi. For modes in general see Modality in Early Ming Qin Tablature.

The music of this version of Guan Ju often seems more diatonic than pentatonic.

| \ Rel. Pitch

Section \ |

A | Bb | B | C | C♯ | D | Eb | E | F | F♯ | G | G♯ | diads | Total |

| 1 | 18 | 1 | 3 | 15 | 39 | 9 | 8 | 22 | DG/AD/AD | 118 | ||||

| 2 | 27 | 3 | 19 | 5 | 32 | 7 | 1 | 1 | 26 | DA | 122 | |||

| 3 | 12 | 5 | 32 | 1 | 9 | 11 | 70 | |||||||

| 4 | 18 | 7 | 6 | 35 | 1 | 17 | 5 | 28 | 117 | |||||

| 5 | 15 | 2 | 4 | 23 | 8 | 3 | 17 | 73 | ||||||

| 6 | 6 | 3 | 14 | 8 | 1 | 10 | 42 | |||||||

| 7 | 61 | 1 | 31 | 13 | 7 | 2 | 34 | 149 | ||||||

| 8 | 13 | 5 | 6 | 30 | 15 | 2 | 24 | 95 | ||||||

| 9 | 10 | 2 | 3 | 22 | 5 | 20 | AD | 63 | ||||||

| 尾聲 Coda | 4 | 6 | 3 | DG | 14 | |||||||||

| Totals | 184 | 4 | 39 | 78 | 246 | 1 | 77 | 31 | 1 | 195 | 7 | 865 |

Octave and unison diads only count as a single note; for runs (gun/fu) only the first and last note are counted. Later versions have ]fewer non-pentatonic notes.

Phrase and section endings (the difference between phrases ending "," and ending "." may be somewhat subjective):

- D,D,G.D,D,D,D/G.A/D,D,G,G.

- D,D,D.G,A.D,G.G,E,G.E,D.BB,G,G.

- D,D,D.A,D,D,G.D,A.

- A.E,A.E,G.E,D,A.D,D,D,D,G.A,E,G,G.

- D.D.G,A.E,D,G.D.G,G.

- A,A,A.D,D,D,D.

- A,A,A.C.//A,A,A,A,A.//A,C,G,G.C,.A.G,G.

- E,A.D,G.E,E,D,A,D,D,D,D,G.A,E,G,G.

- D,D,D,G,G.D,D,G,A,E,G.

Coda: A,D,G/D.

(Return)

3.

Zhi modal prelude (徵意 zhi yi)

The prelude has lyrics as follows (1579 has same character count but changes a few):

午窗香拭裊沉煙,鶴氅舞蹁躚。

酒聖與詩禪蟬,不思凡,風月神仙。

續斷簡殘篇,染雲煙,香霧滿山川。

Green locust and tall willow trees hum anew with cicadas,

the Southern Breeze melody comes out through ice strings.

In the noonday window a scent wafts away as elegant lingering smoke,

like (an immortal in) a crane-feather cloak dancing along gracefully.

The wine sage is in poetic meditation, not conscious of the mundane,

but of the wind and moon and immortal beings.

Continuing broken and incomplete verses, color the clouds and mist,

as a fragrant fog fills the mountains and rivers.

Last line played in harmonics. Translation tentative.

(Return)

4.

Image from

Mao Shi Pinwu Tu Gai

See full image with further information and compare duck image for 雎鳩 jujiu above.

(Return)

5.

First melody not the same as in Shen Qi Mi Pu

As shown here (see also

here), the front of the only surviving copy of this handbook is missing - where it begins is near the end of what was probably the original's third melody. Then, before Guan Ju, comes 徵意 Zhi Yi, the zhi modal prelude mentioned above.

The closing lyrics of this >1505 徵意 Zhi Yi are shown just above. They end as follows:

Xù duàn jiǎn cán piān, rǎn yún yān, xiāng wù mǎn shān chuān.

Continuing broken and incomplete verses...color the clouds and mist,

as a fragrant fog fills the mountains and rivers.

These lyrics and their melody could perhaps be sung as a coda to Guan Ju: melodies 6 and 9 - 12 all end with the same three melodic phrases, though for each the lyrics are different. On the other hand, the lyrics here do not seem particularly related to the theme of Guan Ju.

(Return)

| 6. Confucian commentary used as lyrics | Original tablature for Guan Ju (.pdf) |

The entire Shi Jing is said to have been compiled by Confucius. However, while many of the poems are clearly love songs (including the first five), early Confucians gave them all political meaning. See, for example, this

Wikipedia article that traces the long history of commentary on this poem. Here the music is set to such commentary, much of it directly quoting or closely paraphrasing the neo-Confucian philosopher Zhu Xi (1130 - 1200; see

詩經:朱熹集傳詩經.

);

The entire Shi Jing is said to have been compiled by Confucius. However, while many of the poems are clearly love songs (including the first five), early Confucians gave them all political meaning. See, for example, this

Wikipedia article that traces the long history of commentary on this poem. Here the music is set to such commentary, much of it directly quoting or closely paraphrasing the neo-Confucian philosopher Zhu Xi (1130 - 1200; see

詩經:朱熹集傳詩經.

);

One of the new ideas for interpretation introduced by Zhu Xi was to say the authers were ladies of the court. Memorization of Zhu Xi texts would have been an important part of traditional education (preparing for the civil service exams), and one might speculate as to whether the music here was intended to help in the memorization of such texts. This is part of larger questions such as how the "lyrics" were treated in the past, and how one should treat them at present. While the music is played should, or was it intended that, the lyrics be sung, recited out loud, read quietly or ignored as irrelevant?

The reason for these questions is that, based on my understanding of the music as expressed in my transcription and recording (linked above as well as in the copies of the punctuated text linked below), it is not clear how well the person (or people) who paired the words and music here actually knew and understood both. To examine this keep in mind that, at least until the 20th century, qin music and lyrics were almost always paired following a quite strict traditional formula: one character for each right hand stroke and certain left hand plucks. And to complicate matters even more, the original tablature (see at right) has no punctuation,

With this in mind one should examine three possibilities:

- The music and lyrics were created together

- The lyrics came first, then music was paired to the lyrics

- The music came first, then lyrics were paired to the music

So far, my examination of all this (and this includes the other melodies in the present handbook as well) suggests that the music came first; perhaps in some cases the music was adjusted to fit the lyrics that were being added, but the music was not originally intended for singing. There being no punctuation in the tablature, my understanding of the musical phrasing largely comes from the music itself. And the music, rather than always following the literary phrasing, sometimes does not fit well with the standard punctuation given for the texts in non-musical sources, inluding where the text is quoting Zhu Xi. In addition, in at least some cases the original by Zhu Xi may have been paraphrased to fit the music according to the formula just mentioned. In other cases there may be more than one way of understanding the text, allowing different interpretations of the phrasing.

This needs to be studied further (beginning with a full translation of the text/lyrics). At present, though, an example of where I cannot make the phrasing of the music fit the phrasing of the lyrics can be seen and heard at the end of Section 8 (mm.241-260 of my my transcription. Here, as usual, I chose rhythms based on structures I find in the music, at the same time trying to keep in mind the structures implied by the lyrics. The melody is in zhi mode, with the tonal center on 5 (transcribed here in staff notation as G). There is a fairly common ending to this section: a phrase (mm.251-253) ending on 2 (A) followed by a phrase (mm.254-260) ending on 1 (G). As can be seen, both phrases begin with the same four tablature clusters (comprising 4 notes), but whereas the former directly ends with 7-6-6, the latter goes through an extended elaboration before ending on 6-5-5. This structure requires beginning the phrase at m.251 with the characters "人道", which in Zhu Xi ends a phrase. (For "你那" and other pairing inconsistencies see this and its surrounding footnotes.)

(Return)

7.

召 Shao

"Shao" apparently refers to the family of 召公 Shao Gong, the Duke of Shao. He was a brother of 武王 Wu Wang. Shao became "famous for his benevolent stance towards the people in the south he was entrusted to govern....The Duke of Shao was a functionary in the central government of the Zhou. The post was taken over by heirs of Shao Gong Shi, yet only a few names are transmitted." (China Knowledge, which has a list of the known later Dukes of Shao).

(Return)

8.

Significance of the lyrics (the complete lyrics are

below)

Most versions with lyrics (listed below) focus on the virtues of Wen Wang and his wife. Likewise all the versions with commentary discuss these virtues. This was typical of classical Chinese commentary on the poems in general; it has only been in modern times that commentary has turned to the original romantic themes of many Shi Jing poems.

(Return)

9.

Shi Jing lyrics in Guan Ju compared to

the original lyrics

The original Shi Jing poem has 20 four-character phrases arranged as five verses of four phrases (or two couplets) each each ([{4+4}x2] x 5). Here lines from this original poem can be found only in Section 6, as follows:

求之不得,寤寐思服。展轉返側,展轉反側。 (would be = verse 3 if the second 展轉返側 were 悠哉悠哉 Alas! Alas!)

(Return)

11.

Tracing Guan Ju (tracing chart)

The chart below is based largely on Zha Guide 11/109/179 關雎曲 Guan Ju Qu. In all, at least 54 handbooks from >1505 to 1894 include Guan Ju or a related title.

Of these, nine early handbooks include lyrics:

Taigu Yiyin (1511), lyrics are Shi Jing poems 1-5

Xilutang Qintong (1525); Section 5 is set to the opening 4x4 verse

Faming Qinpu (1530); different new lyrics, but related to ZYSZQP

Longhu Qinpu (1571); like 1511, but sectioning is different

Chongxiu Zhenchuan Qinpu (1585): lyrics quite similar to those in ZYSZQP

Lixing Yuanya (1618): two versions, #1 like 1585, #2 like 1511 but only poem 1 and only for 5 strings (one of 13)

Lixuezhai Qinpu (1730): again new lyrics but still focused on virtues of Wen Wang's queen

Lüyin Huikao (1835); syllabic setting like 1618, #2 but different melody

No later versions seem to have lyrics.

(Return)

12.

Differing lyrics

For versions with the complete original Shi Jing lyrics see

1511 and 1618 in the

chart below. Those with partial Shi Jing lyrics usually place them in their Section 6. The quite varied similarity of the lyrics of these other versions might be accounted for by the likelihood that they were never actually sung. Someone would learn a version with lyrics but in the process of making it his or her own would change the melody. Changing the melody usually required changing the lyrics because, whether actually sung or not, they had to accord with the standard pairing method. This is probably one reason why 1730 has only the partial Shi Jing lyrics in its Section 6: it was revising an earlier melody, not creating a new longer one, and these other versions mostly have a short version of the Shi Jing lyrics in their Section 6.

(Return)

13.

Original preface

The original Chinese preface can be seen under

關雎.

(Return)

14.

Music and lyrics (compare

1511; timings below

follow my recording 聽錄音)

The original Chinese section titles are (see translation; see also my revised transcription):

01.06 2. 大鬧周召 (大閒周、召 ?)

02.09 3. 即物興人

02.40 4. 舉德稱行

03.26 5. 風化天下

04.00 6. 相與和鳴 (泛音; 見 詩經,第一、第三段)

04.19 7. 禮正婚姻

05.19 8. 德侔天地

05.59 9. 配享宗周

06.37 入終聲(泛音:10段,雎鳩和樂? 看 《禪真逸史》)

06.54 曲終

The lyrics here begin by using phrases from commentary on the Shi Jing ("江沱汝漢" are the Yangzi, Tuo, Ru and Han rivers, all flowing through the southern part of Zhou territory; "河洲" is a general name for the area. See, e.g., commentary by Zhu Xi at ctext.org, etc.)

Original lyrics for the >1505 Guan Ju. (pdf of lyrics only;

pdf of same from

Zha's Guide)

The complete original Chinese section titles and lyrics are as follows. The phrasing, which follows my understanding of the music, is in places somewhat different from that in Zha's Guide. Here below, two consecutive punctuation marks without text between them means that the previous phrase should be repeated; it is not clear whether it is intended that the lyrics also be repeated.

Section 1 was originally translated by 趙鵬 Zhao Peng; Sections 2 to 7 by 朱元虎 Zhu Yuanhu.

- 關雎 Ospreys Cry

- 王雎善匹 (00.00)

Wáng jū shàn pǐ

The prince-like osprey finds a good marriage江、沱、汝、漢河洲,赤沙碧草地偏幽。

Jiāng, Tuó, Rǔ, Hàn hé zhōu, chì shā bì cǎo dì piān yōu.

On islets of the Jiang, Tuo, Ru, and Han rivers (?), secluded land with ruby sands and emerald grass.看並立王鳩,雌雄聲應也氣求,

Kàn bìng lì wáng jiū, cí xióng shēng yīng yě qì qiú,

See the pair of perched ospreys (?), male and female they tweet in harmony.關關相友和柔。 。

Guān guān xiāng yǒu hé róu. .

"Guan Guan" (they call out), amicably and gently, .雙宿食,雙並游,鳩無相狎愛恣優那游。

Shuāng sù shí, shuāng bìng yóu, jiū wū xiāng xiá ài zī yōu nà yóu.

In pairs they rest and eat; in pairs they drift; but these birds are never inappropriate though carefree as they drift.水禽鳥,難為儔,鳧鷖狀類,德不相侔。

Shuǐ qín niǎo, nán wéi chóu, fú yī zhuàng lèi, dé bù xiāng móu.

Waterfowl rarely pair off; as for the likes of ducks and gulls, their virtue is not comparable.摯而那有別,關雎冠於毛傳首,

Zhì ér nà yǒu bié, guān jū guān yú Máo chuán shǒu,

Because they keep their affection though apart, "Guanju is at the pinnacle of the poetry passed on by Mao.思憶憶,周文王后妃有聖德,宜相好逑。

Sī yì yì, Zhōu Wén Wáng hòu fēi yǒu shèng dé, yí xiāng hǎo qiú.

Always remember this, King Wen's queen had great virtue, making a fine consort.

- 大閒(閑)周、召 (01.06)

Dà xián (xián) Zhōu, Shào

Very gentle are (the wives of the royal famiy of) Zhou and Shao大閑那《周》、《召》。

Da Xian na "Zhōu" "Shào".

There is that basic behavior rule for Zhou and Shao.雎鳩也有定偶,那死生同命,

Jū jiū yě yǒu dìng ǒu, nà sǐ shēng tóng mìng,

The ospreys also have their destined partner, sharing the same fate in life and death.詩人托物的那於以起賦比興。

Shī rén tuō wù dì nà yú yǐ qǐ fù bǐ xìng.

The poet employs the use of metaphor, so as to begin with fu, bi and xing.周南召南的那諷誦絃歌之聲,相應和鳴。

Zhōu nán Zhào nán dì nà fèng sòng xián gē zhī shēng, xiāng yìng hè míng.

Zhou South and Zhao South, that the sound of reading, chanting, playing music and singing, all resonate in harmony.后妃聖德,纓閒貞靜也,有以宜配文王。 (幽閒 is elsewhere 纓閒)

Hòu fēi shèng dé, yīng xián zhēn jìng yě, yǒu yǐ yí pèi Wén Wáng.

The queen is of sagely virtue, elegant, gentle, loyal, quiet, so as to match King Wen.亦若雎鳩的那陰陽定偶,關關然相應如賓友。

Yì ruò jū jiū dì nà yīn yáng dìng ǒu, "guān guān" rán xiāng yìng rú bīn yǒu.

Just like the yin-yang mating of the ospreys, "Guan Guan" (they call), amicably and gently, as if answering guests and friends.思憶憶也。

Sī yì yì yě.

Ai yah!周文王后妃有聖德,宜相好求。

Zhōu Wén Wáng hòu fēi yǒu shèng dé, yí xiāng hǎo qiú.

King Wen's queen had great virtue, making a fine consort.- 即物興人 (02.09)

Jí wù xìng rén

Be close to things and begin with human virtue即鳥聲之和,與女德之和。

Jí niǎo shēng zhī hé, yǔ nǚ dé zhī hé.

Be close to the harmony of the bird’s singing, and begin with the peace of womanly virtue.致貞淑,南北絃歌。

Zhì zhēn shū, nán běi xián gē.

Become loyal and gentle, play stringed instruments and sing songs from south to north.美成內治,普德而多,

Měi chéng nèi zhì, pǔ dé ér duō,

Glorious achievements and self inner governance, virtues become many and spread around.善匹善處而如何,而如何。

Shàn pǐ shàn chǔ ér rú hé, ér rú hé.

Be good at matching with a partner, and at living with the partner, what else can one do, what else can one do?宗廟之主,綱紀而呵,

Zōng miào zhī zhǔ, gāng jì ér hē,

Master of the ancestral temple, (The master) of order and law, ah.

統理天下,萬物而呵,

Tǒng lǐ tiān xià, wàn wù ér hē,

To rule the world, (to rule) all things, ah.被之筦絃,房中之樂。 (筦絃 is the same as 管絃)

Bèi zhī guǎn xián, fáng zhōng zhī lè.

Enjoy the orchestral music, (and) domestic happiness.

- 舉(興?)德稱行 (02.40)

Jǔ (xing?) dé chēng xíng

Praise (her) virtue and acclaim (her) conduct《關雎》后妃,德舉全體。

Guān jū hòu fēi, dé jǔ quán tǐ.

The queen (in the poem) "Guan Ju" has all good behavior,(「仝后」?)

(Tóng hòu?)

("As with later"??? Here and below mention is made of Shi Jing #1, #2, #4 and #5; why not #3 卷耳 Juan Er?)貴而勤,

Guì ér qín

(She is) noble and hardworking.《葛覃》志行在己,

"Gé Tán" zhì xíng zài jǐ,

In "Cloth plant" intentions and behavior reside in oneself.《樛木》《螽斯》德惠及人,福履綏之矣。

"Jiū mù" "Zhōng sī" dé huì jí rén, fú lǚ suī zhī yǐ.

In "Trees with drooping branches" and "Locusts" the virtue benefits others and blessings follow.合太和,致中和,茂德音,呵,

Hé tài hé, zhì zhōng hé, mào dé yīn hē,

Accord with supreme harmony, attain central harmony, foster virtue and reputation, ah.關雎流水之河,

Guān jū liú shuǐ zhī hé,

The ospreys call as they float on the river,相與和樂, ,

Xiāng yǔ hé lè, ,

Being with each other in harmonny,相與和樂,,和樂。於是德化大成,

Xiāng yǔ hé lè, , hé lè. Yú shì dé huà dà chéng,

With each other in harmony, in harmony, so moral education brings great success.於內相從,汝漢江沱。

Yú nèi xiāng cóng, Rǔ, Hàn, Jiāng, Tuó.

Inside, the ospreys follow each other to the Ru, Han, Jiang and Tuo rivers.被之管絃,而為房中之樂。

Bèi zhī guǎn xián, ér wéi fáng zhōng zhī lè.

(So) enjoy orchestral music and the happiness of love.

- 風化天下 (03.26)

Fēng huà tiān xià

(Like) the wind (, the queen) guides the world女德在貞淑,女行在昭德。

Nǚ dé zài zhēn shū, nǚ xíng zài zhāo dé.

Womanly virtue lies in loyalty and gentleness, womanly behavior is a display of virtue.慎固幽深,太姒也風化天下, (幽深 is elsewhere 纓深)

Shèn gù yōu shēn, tài sì yě fēng huà tiān xià,

Being prudent, firm, gentle and profound, Tai Si (wife of Wen Wang) moralizes people around the land.正位於後宮,其儀不忒。

Zhèng wèi yú hòu gōng, qí yí bù tè.

In the imperial harem ensuring proper conduct (means) her behavior must have no mistakes.關雎風化南而北,

Guān jū fēng huà nán ér běi,

"Guan Ju" brings morality in both south and north.民俗歌謠,的那閨門鄉黨而邦國。

Mín sú gē yáo, dì nà guī mén xiāng dǎng ér bāng guó.

Folk songs (bring it) from family to village and thence to country.上天作合非偶然,誦詩三百。

Shàng tiān zuò hé fēi ǒu rán, sòng shī sān bǎi.

Heaven coordinating in this way is not accidental: so do sing the Three Hundred Poems (i.e., the Shi Jing).

- 相與和鳴(泛音; 04.00)

Xiāng yǔ hè míng

(Sing out in harmony to each other)關關雎鳩,在河之洲。

Guān guān jū jiū, zài hé zhī zhōu.

A pair of ospreys at riverside are cooing;窈窕淑女,君子好逑。

Yǎo tiǎo shū nǚ, jūnzǐ hǎo qiú.

There is a maiden fair whom a young man is wooing.求之不得,寤寐思服。

Qiú zhī bù dé, wù mèi sī fú.

Pursue but not get, so he cannot fall asleep.展轉返側,展轉反側。 (? ➝ 悠哉悠哉,展轉反側。?)

Zhǎn zhuǎn fǎn cè, zhǎn zhuǎn fǎn cè.

Tossing and turning in his plight; tossing and turning in his plight. (?)

- 禮正婚姻 (04.19)

Lǐ zhèng hūn yīn

A correct (wedding) ceremony (leads to) a successful marriage禮正婚姻,

Lǐ zhèng hūn yīn

A correct (wedding) ceremony (leads to) a successful marriage悠哉悠哉。 (compare 優哉優哉)

Yōu zāi yōu zāi. (compare Yōu zāi yóu zāi)

Longing, longing.//配匹之際,生民之始,

Pèi pǐ zhī jì, shēng mín zhī shǐ,

The occasion of marriage is a beginning for humans,萬福之原,萬福原, , ,

Wàn fú zhī yuán, wàn fú yuán, // .

And is the source of good blessings, the source of good blessings.宜配君子焉。//

Yí pèi jūn zǐ yān.

Suitable to making matches for gentleman.(Repeat these last three lines)

感於性,

Gǎn yú xìng,

(All music) originates from human nature,以發於情,而宰於心。成為詩,形於聲,

Yǐ fā yú qíng, ér zǎi yú xīn. Chéng wéi shī, xíng yú shēng,

Then is expressed through human emotion, controlled by the heart; with poetry it takes the form of song,響諸音樂,皆得乎和平,婚禮也,

Xiǎng zhū yīn yuè, jiē dé hū hé píng. Hūn lǐ yě.

Resounding as music, and all this bringing peace and harmony; as for a marriage ceremony,宜其時,

Yí qí shí.

It is an appropriate time.興於《桃夭》,形於江漢,其為誰,其為誰。

Xìng yú "Táo Yāo", xíng yú Jiāng Hàn", qí wèi shuí, qí wèi shuí.

Begin with (poem #6) "Tao Yao” shaping Jiang Han river, for whom? For whom?

- 德侔天地 (05.19)

Dé móu tiān dì

(The king and queen have) virtue comparable to that of heaven and earth賢其賢,賦性而全乎天。

Xián qí xián, fù xìng ér quán hū tiān.

Respect the worthy, all of nature fills all of heaven.太姒體坤承乾,至靜至健,賢其賢。

Tài Sì tǐ kūn chéng qián, zhì jìng zhì jiàn, xián qí xián.

Tai Si embodies the earth (坤) and undertakes heaven (乾), and so quietly and vigorously respects the worthy.文王也,后妃也,德侔天地,

Wén Wáng yě, hòu fēi yě, dé móu tiān dì,

King Wen and his queen, they have virtues that match nature,開分萬化之原。

Kāi fēn wàn huà zhī yuán.

And so they start as the source of many changes.三綱以正,,

Sān gāng yǐ zhèng, ,

The three cardinal guides are in the right place,六紀俱全,,

liù jì jù quán, ,

The six relationships are all complete.賢 賢張理,上下整齊,

Xián xián zhāng lǐ, shàng xià zhěng qí,

Respecting the worthy and open to governance, from top to bottom people are all in their appropriate place.人道你那倫理綿綿。

Rén dào nǐ nà lún lǐ mián mián.

People tell you the ethic stretches long and unbroken.思無邪也,詩冠乎三百篇。。

Sī wú xié yě, shī guān hū sān bǎi piān.

Abundant and rich, this poem (Guan Ju) is at the head of the Three Hundred Poems collection (the Book of Songs).

- 配享宗周 (05.59)

Pèi xiǎng zōng Zhōu

Worthy of eternal worship in the Zhou family temple王政呵,閨門始,

Wáng zhèng hē, guī mén shǐ,

Royal governance begins with the rule of family.身化天下,文王所致。

Shēn huà tiān xià, Wén Wáng suǒ zhì.

Bring morality to the land is what Wen Wang does.關雎之詩,

Guān jū zhī shī,

With the poem “Guan Ju”,內系賢助相維之,內系賢助相維之。

Nèi xì xián zhù xiāng wéi zhī, nèi xì xián zhù xiāng wéi zhī.

From its content the sage maintains kingly governance, from its content the sage maintains kingly governance.玉葉繼金枝,

Yù yè jì jīn zhī,

Elegant and noble people,樂享宗周傳世系,

Lè xiǎng zōng zhōu chuán shì xì,

They are happy to ensure the descendant line of Zhou dynasty.好合那兮,得其那宜也,

Hǎo hé nà xī, dé qí nà yí yě).

They match properly with each other, and get what is suitable:萬古名垂。

Wàn gǔ míng chuí.

A great eternal reputation.聲入終 (06.37)

Sound goes into an ending.

(In the recording interpreted to mean here 加泛音亦可 you can play a harmonic coda) - 大閒(閑)周、召 (01.06)

Glossary of terms in this translation (partly by 朱元虎 Zhu Yuanhu):

By the start of the Former Han period, the collection of Book of Songs was known in three officially recognized versions: of Lu 魯, Qi 齊 and Han 韓 as well as in the private version of Mao Gong 毛公. The second of the entries for the Mao version in the Han Shu reads, Mao shi gu xun zhuan san shi juan 毛詩故訓傳三十卷, that is, Mao chuan 毛傳. (See Michael Loewe, Early Chinese texts: a bibliographical guide, England: Institute of East Asian Studies, 1993, pp.416.)

More explanations could be added.

Return to top

In fact, “Guan Ju” is the first poem in the Shi Jing. "Mao chuan" is a book of commentary that explains the meaning of the Shi Jing in Confucian terms. Therefore, the sentence here can be translated as this: "'Guan Ju' is at the pinnacle of poetry of 'Mao chuan'".

(Return)

Appendix: Chart Tracing Guan Ju

Based mainly on Zha Fuxi's Guide

11/109/179.

|

琴譜

(year; QQJC Vol/page) |

Further information

(QQJC = 琴曲集成 Qinqu Jicheng; QF = 琴府 Qin Fu) |

|

1. 浙音釋字琴譜 [here]

(>1505; I/203; listen) |

8+1L; zhi mode;

lyrics throughout paired in

standard way; Section 6 (I/205; harmonics):

"關關雎鳩,在河之州。....".

Tonal centers are 5 and 2 so most non-pentatonic notes are up a third from them: 7 and 4 (B & F in chart) |

|

2. 謝琳太古遺音

(1511; I/277) |

Guan Ju Qu; 10L, but marked by circles rather than numbered. Lyrics are first five poems of 詩經 Shi Jing, repeated.

Music very different but still related; tonal centers still 5 and 2 so only non-pentatonic notes are 7 and 4 |

|

. 黃士達太古遺音

(1515; ___) |

Same as 1511

|

|

3. 西麓堂琴統

(1525; III/152) |

8 (5L); music at first like >1505 but seems to combine former sections 2 and 3; lyrics only in Section 5 (harmonics; compare >1505 Section 6) and they are only "關關雎鳩,在河之州。 窈窕淑女,君子好逑。" (III/153); after this more differences.

On this YouTube recording by 徐曉英 徐曉英 Xu Xiaoying she sings the lyrics. |

|

4. 發明琴譜

(1530; I/366) |

8L; similar music throughout and lyrics paired throughout as with >1505 but the lyrics are very different and it is not clear whether the music is different because of the new lyrics or new lyrics had to be made to fit the changed music. Strange errors (e.g., writing "上 slide up" when going to a lower position); harmonics only in Section 6 ("關關雎鳩....") |

|

5. 風宣玄品

(1539; II/261) |

10; connected throughout to >1505 but no lyrics and many notes changed. In expanding from 9 sections to 10 it divided the earlier Sections 1 and 2 to become 1 to 4, so harmonics are now in Section 8 instead of 6, and its Section 9 then combines the earlier 7 and 8. |

|

6. 梧岡琴譜

(1546; I/430) |

8; related to >1505 but actually very different; no lyrics; copied in 1561#2; Section 5 includes (!) Section 6 讀書聲

Sound of reading books. Section 7 ends with "从雎至鳩" (i.e. repeat Section 4) and Section 8 begins with"从關至關" (i.e., repeating a passage from Section 1)

this YouTube (also on BiliBili) is a metal string recording by 胡思琴 Hu Siqin. |

|

7. 步虛僊琴譜

(1556; III/285) |

9; very similar to 1546 (see especially Section 6: not called 讀書聲; it then seems to expand Section 7 and add a Section 8 by writing out the repeats just mentioned in 1546) |

|

8. 太音傳習

(1552; IV/134) |

10; Sections are titled; more differences but still related throughout

|

|

9. 太音補遺

(1557; III/376) |

8; still related

|

|

10a. 琴譜正傳

(1561; II/494) |

7; "yu mode!"; related but quite different (compare next). "Yu mode" should make relative tuning be considered as 5 6 1 2 3 5 6, and some notes seem changed to be more pentatonic, but too many of the original notes seem to remain and I cannot say that I have a sense of the actual mode here in terms such as I describe, e.g., here |

|

10b. 琴譜正傳

(1561; II/503) |

8; same as 1546

|

|

11. 龍湖琴譜

(1571; 琴府/255) |

9TL; titles are not numbered and differ from >1505; lyrics ≅

>1505 (omits 的 & 那) but music seems simpler

|

|

. 新刊正文對音捷要

(1573; #53) |

Same as 1585?

|

|

12. 五音琴譜

(1579; IV/231) |

10

|

|

13. 重修真傳琴譜

(1585; IV/438) |

10L; related melody; lyrics of S1-S9 are like >1505;

|

|

14. 玉梧琴譜

(1589; VI/56) |

8

|

|

.

真傳正宗琴譜

(1589; VII/205) |

10+1; not in 1589 edition

|

|

15 真傳正宗琴譜

(1609; VII/205) |

10+1; many differences but still related

|

|

16. 琴書大全

(1590; V/504) |

14+1; quite different but still related

|

|

17. 文會堂琴譜

(1596; VI/237) |

8

|

|

18. 藏春塢琴譜

(1602; VI/397) |

Same as 1589?

|

|

19. 陽春堂琴譜

(1611; VII/401) |

10

太古正音欽佩 |

|

20.

松絃館琴譜

(1614; VIII/134) |

10; online recording by 王鐸 Wang Duo

|

|

21.

理性元雅

(1618; VIII/246) |

10L; lyrics like 1585 but different section titles

|

|

.

理性元雅

(1618; VIII/309) |

3; only standard qin setting using only the complete lyrics of Shi Jing #1? (compare 1739, 1745 and 1835)

New melody using only five strings |

|

22. 樂仙琴譜

(1623; VIII/382) |

Guanju Qu; 10; related

|

|

23. 古音正宗

(1634; IX/340) |

9

|

|

24. 義軒琴經

(late Ming; IX/432) |

10 (#1 is missing)

|

|

25. 徽言秘旨

(1647; X/145) |

10

|

|

. 徽言秘旨訂

(1692; fac/) |

Same as 1647?

|

|

26. 友聲社琴譜

(early Qing; XI/184) |

10"章"

嚴譜; afterword |

|

27. 琴苑新傳全編

(1670; XI/376) |

10; compare previous

|

|

28. 大還閣琴譜

(1673; X/397) |

10; related but also more pentatonic

Transcribed and recorded by 紀志群 Ji Zhiqun (YouTube) |

|

29. 澄鑒堂琴譜

(1689; XIV/259) |

10

|

|

30. 蓼懷堂琴譜

(1702; XIII/249) |

10; zhi yin

|

|

31. 誠一堂琴譜

(1705; XIII/384) |

10

|

|

32. 五知齋琴譜

(1722; XIV/480) |

10+1; contains numerous interlineal comments on how to play expressively, as well as ending comments on how the music itself reflects what was being expressed by the original poem |

|

33. 存古堂琴譜

(1726; XV/255) |

10

|

|

34. 光裕堂琴譜

(~1726; XV/334) |

10

|

|

35. 立雪齋琴譜

(1730; XVIII/28) |

?L; 關雎傳 Guanju Zhuan; "古譜新詞 old music new words" (music is related, "lyrics" are actually commentary ["傳"] by Zhu Xi);

Lyrics, which follow standard pairing, begin, 美哉,關雎之詩,其言文王后妃之德乎詩.... |

|

36. 琴學練要

(1739; XVIII/138) |

(治心齋琴譜); 3; gong yin; "元白伯新譜"

another new melody; lyrics = Shi Jing #1 but it is not a standard pairing: many more notes than words |

|

37. 春草堂琴譜

(1744; XVIII/252) |

中呂均商音 ("4th string is shang"); 10; the afterword by 晴峯先生 adds the comment, "如俗以讀書聲撫之,失之遠矣 if you play in a common way using the sound of reciting the text you lose the profunditiy." |

|

. 大樂元音

(1745; XVI/370) |

Guan Ju Zhang; 3; Shi Jing lyrics;

Note names, no tablature |

|

38. 琴香堂琴譜

(1760; XVII/87) |

10

|

|

39. 自遠堂琴譜

(1802; XVII/373) |

10; shang yin

|

|

40. 裛露軒琴譜

(>1802; XIX/266) |

10; "from 1722"

|

|

41. 響雪山房琴譜

(>1802; XIX/390) |

10

|

|

42. 琴譜諧聲

(1820; XX/154) |

10; "角商 jiao shang"; "S9 = S4 but change its ending";

Afterword: "from 將雲章l; also mentions 1614 and 1673 |

|

43. 峰抱樓琴譜

(1825; XX/331) |

10

|

|

44. 鄰鶴齋琴譜

(1830; XXI/52) |

10; #9 from #4; no mode indication but related

|

|

. 律音彙攷

(1835; XXII/192) |

Seven settings in all: 173, 177, 180, 186 (qin), 192 (qin), 198 (se), 204 (聲字譜)

173, 177, 180, 204 have Shi Jing lyrics and note names only (details) |

|

45. 悟雪山房琴譜

(1836; XXII/327) |

10; 中呂均商音

|

|

46. 張鞠田琴譜

(1844; XXIII/332) |

10; tablature + note names in popular notation

|

|

47. 稚雲琴譜

(1849; XXIII/453) |

10; includes phrase count

|

|

48. 蕉庵琴譜

(1868; XXVI/55) |

10; shangyin

Preface |

|

49a. 天聞閣琴譜

(1876; XXV/221) |

10; shangyin yu diao; " = 1744"

|

|

49b. 天聞閣琴譜

(1876; XXV/224) |

10; shangyin; " = "1702"

|

|

50. 天籟閣琴譜

(1876; XXI/160) |

10

|

|

51. 響雪齋琴譜

(1876; ???) |

originally part of 1807?

10; zhi yin (not in QQJC: info from Zha Guide) |

|

52. 綠綺清韻

(1884; XXVII/393) |

10, but QQJC edition cuts off in middle of 7

|

|

53. 枯木禪琴譜

(1893; XXVIII/90) |

10

|

|

54a. 琴學初津

(1894; XXVIII/276) |

10; huangzhong jun shang yin

Long afterword |

|

54b. 琴學初津

(1894; XXVIII/340) |

10; 關雎,復古譜 Guan Ju Fugu Pu ; "黃太調宮音 Huangtaidiao gongyin";

Standard tuning; long afterword speaks of "fu gu returning to old" by omitting lyrics |

Return to the Zheyin Shizi Qinpu index or to the Guqin ToC.