|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Xianweng Cao Singing Xian-Weng Tracing chart Beginning HIP Tiaoxian Pin References 5 pdfs |

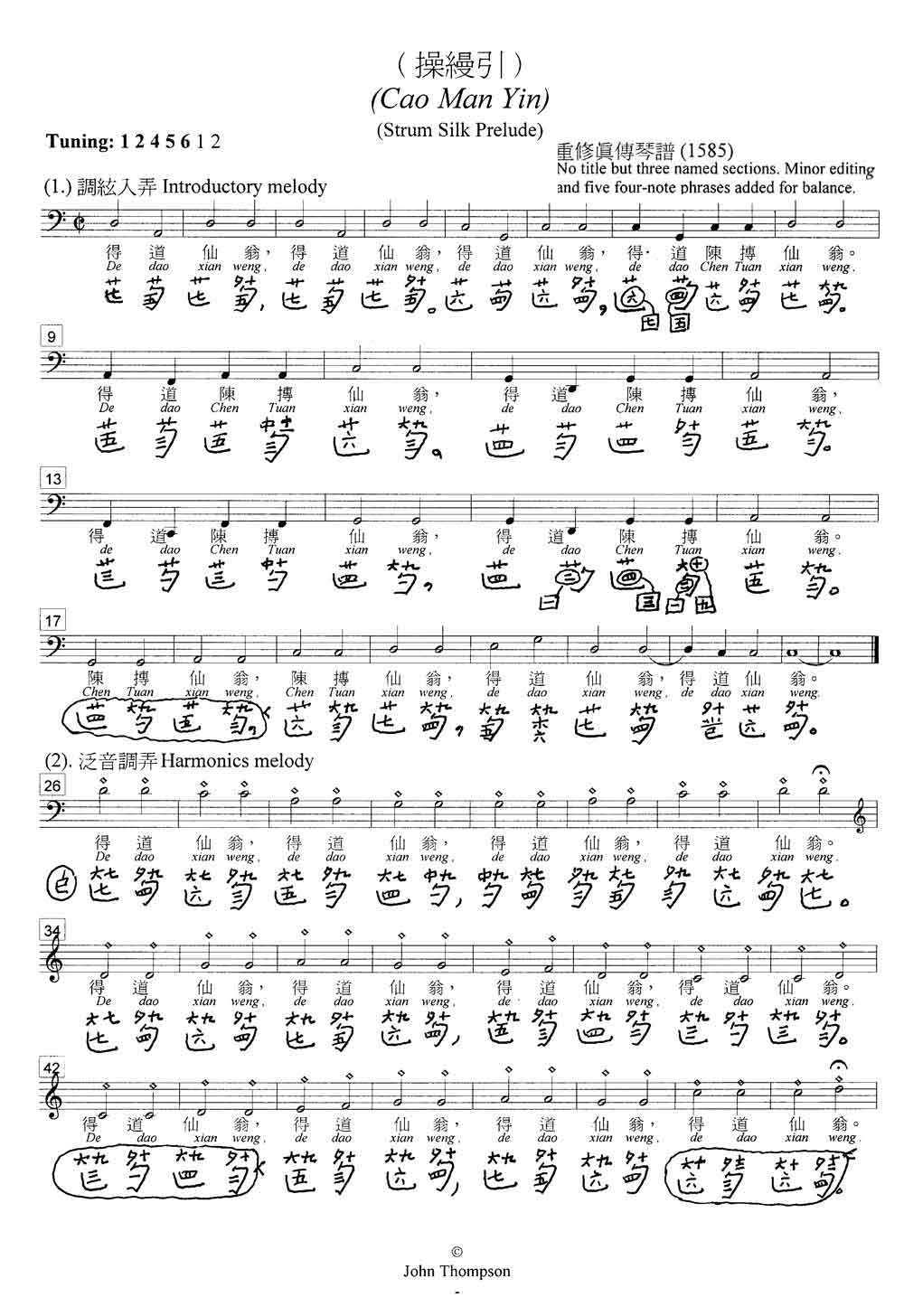

1585 staff

1585 Videos

|

|

Strum Silk Prelude

- Like Xianweng Cao (see also xian-weng sound), these preludes invoke the Song dynasty recluse Chen Tuan 2 |

操縵引 1

Caoman Yin |

| - Standard tuning (no mode indicated): 5 6 1 2 3 5 6 and/or 1 2 4 5 6 1 2 3 | 1585 Caoman Yin (pdf / listen) |

- Xianweng Cao seems to be a

relatively new title:

see video;

- Xianweng Cao seems to be a

relatively new title:

see video;

Caoman Yin versions are now often retroactively called Xianweng Cao; the earliest are dated:

- 1552; earliest known version; see original and transcription; from longhand tablature; listen: Bb / A. 4

- 1557; has longer commentary; see original and transcription; listen.

- 1585; see section titles and commentary. See videos: Sections 1, 2, 3; full transcription and recording linked at right.5

- 1589; original hard to read; identical tablature in 1676; listen with video from Japanese garden

The discussion here concerns versions of a melody that was often the first piece a student would learn. It has most commonly been known by any of these three names:

Until the 20th century it seems that the "Xianweng lyrics" were always related to a version of the melody presented here, but never in the title. In fact, the first surviving version (1552) has no lyrics and no mention at all of "Xian Weng"; the second (1557) mentions "Xian Weng" but the preface connects him to Jiuhua Shan, a mountain range in Anhui province northwest of Huangshan; it is famous for its Buddhist connections and Chen Tuan is rarely associated with Buddhism. Since it is only with the third version (1585) that "Xianweng" is connected to Chen Tuan, it seems likely that this was a new connection based on "Xianweng" being a term often applied to other famous Daoist recluses/immortals.6

On the other hand, when I began studying guqin in 1974 the only "Xianweng Cao" I knew was a separate melody that uses similar lyrics and is also chant-like, but its music, though related, is also quite different and apparently of more recent origin.7

It is particularly the earliest versions of Caoman Yin that had lyrics about Xian Weng attached, and it presumably is for this reason that "Xianweng Cao" came to be used as an alternate title. However, it never seems to have been used as the primary title of a melody until it was applied to the Xianweng Cao discussed here on a separate page. Today versions of both melodies are used simply as beginners' melodies, and it is quite likely that both of them originated for this same purpose. The repetition of the same pitches played on open strings then stopped strings (sometimes called "xianweng yin"8) helps train the ear to correct tuning as well as to play in tune.

In any event, the repetitious and straightforward nature of the melodies as well as the lyrics (see

in transcription) allow it to serve more advanced players both as a sort of warm up melody and as a way of centering oneself prior to playing: the effect of playing it in a calm manner might be compared to the effect that making ink was intended to have on someone preparing to do calligraphy.9

Earliest versions usually divided in three parts, such as in

1552 and 1557

In 1585 this is the first of three sections, but in 1589 and later the second and third were usually dropped.

This is the most common name used today; however, it does not seem to have been used officially as a title until the late 20th century.

| 陳摶:仙翁 Chen Tuan, the "Transcendent Venerable One" | Chen Tuan: "Sleeping meditation" 10 |

In all cases, "Transcendent Venerable One" refers to the 10th century recluse Chen Tuan: this was one of his nicknames. As outlined in

this footnote, Chen Tuan is thought of primarily as a Daoist, but he has also been connected to the development of neo-Confucianism. Early sources mention his ability to sleep (the image at right comes from one of the manuals of "sleeping meditation" said to have been inspired by this). Later this and other of his reputed meditation practices led to him being associated with a number of "internal arts".

In all cases, "Transcendent Venerable One" refers to the 10th century recluse Chen Tuan: this was one of his nicknames. As outlined in

this footnote, Chen Tuan is thought of primarily as a Daoist, but he has also been connected to the development of neo-Confucianism. Early sources mention his ability to sleep (the image at right comes from one of the manuals of "sleeping meditation" said to have been inspired by this). Later this and other of his reputed meditation practices led to him being associated with a number of "internal arts".

The association of Chen Tuan with sleep is particularly interesting here. The Chen Tuan lyrics clearly are about him, not by him; there seem to be no extant stories that tell of him playing the qin; and it is not clear how this melody came to be associated with him. On the other hand, the traditional sound of the qin, with its thick wood and silk strings, is by its very nature calming (some would say soporifice), and see this interpretation of the famous saying, 琴者禁也: Qin embodies restraint. Restraint may seem at first the opposite of calmness and relaxation, but because the instrument itself is restrained in its sound, taking full advantage of its rich potential requires the player to realize fully the inner beauty of that restraint. It is the life's tensions that are restrained, and perhaps it is this that can induce sleep.

Here "harmony" seems to mean "harmonic relationship" between two strings, here one string is played open, the other is stopped or a harmonic

(xian-weng sound). After the opening ("beginning"") section, the "big" relationship is strings an octave apart; the small relationship is two or three strings apart.

There are no lyrics. Because its preface, which does not mention Xianweng, has only the central part of the preface to the

1557 version, and its comments with each of the three sections are briefer than those in 1557, it is the 1557 commentary that is translated here.11

Later versions of Caoman Yin can be found in many early qin handbooks, under various titles.17 In addition, there are a number of essays (often called Tuning Method) that mention Xian Weng;18 they may or may not be related to something called a "Xianweng method".19

As for melody titles, though, the only related use of "Xianweng" I have yet found in the old handbooks so far seems to be "Tiao Xianweng Ge",20 the title of a version of Caoman Yin beginning with Qinxue Lianyao (1739). This version, which could perhaps be described as Tuning by Singing (regarding which see

under Xianweng Cao), has characteristics of both the original and the present versions.21

These melodies are almost always included with the essays at the beginning of the handbooks, rather than with the regular melodies. Perhaps this indicates they were considered only as meditations (or as introductory exercises).

The preface to the 1557 version suggests that unless one begins with simple melodies, one will never master the qin.22 My own teacher told me that the seemingly most simple pieces were the ones that required the greatest art.23 This still leaves open the question of whether this piece is more meditation or more fingering exercise.

(This section forms the preface to 1552

(see the original text).

He then took out from his sleeve the tablature for Adjusting the Strings Prelude (Caoman Yin), in three sections. It was written by Shi Cao of Wei. The Daoist explained it. The Daoist called himself Woodcutter of Jiuhua Mountains.

(I.) Beginning Harmony, The notes are fixed

(Tentative translation26)

(II.) Big (Gap) Harmony, Master and vassal have virtues in harmony

(Tentative translation27

(III.) Small (Gap) Harmony, The notes are harmonious

(Tentative translation28)

Now, for seasoned qin players, indeed there is no need to concern themselves with this. But as for beginners, who desire that their study of the qin be complete — if they do not grasp these things, what benefit can they obtain?

Alas! If students, having learned a little in youth and practiced on into old age, still does not understand these, then what can truly be said of their relation to the qin?

The video was shot by Tiffany Lau in March 2019; it was then edited by Jim Shum 沈聖德, a teacher at 台北藝術大學.

The lyrics of the version I originally learned are included under Xianweng Cao.

1.

Strum Silk Prelude (操縵引 Caoman Yin)

These explanations are not very clear to me. The definition 操縵,操弄琴絃 suggests simply playing the qin strings. Here, after the passage from the Book of Rites, although the quotations also give alternate meanings, in the end I am not sure what the writers are suggesting is necessary for proper musicianship. The Ji Shuo of Chen Hao (1261 - 1341, see Giles) was a standard text on the Book of Rites. Yu Xin (513 - 581) was a noted poet; no further information on his Yue Guo Gong Ji. Zhang Dai (1599 - 1684?), nicknamed Tao'an, was a noted writer and qin player. Huang Sheng (also 17th c.) was a writer from 歙縣 She county in Anhui.

Recorded versions of Xianweng melodies

The present page takes special note of the four versions of this melody that I have transcribed and played: these are also the four earliest surviving versions of this melody, published in the following handbooks.

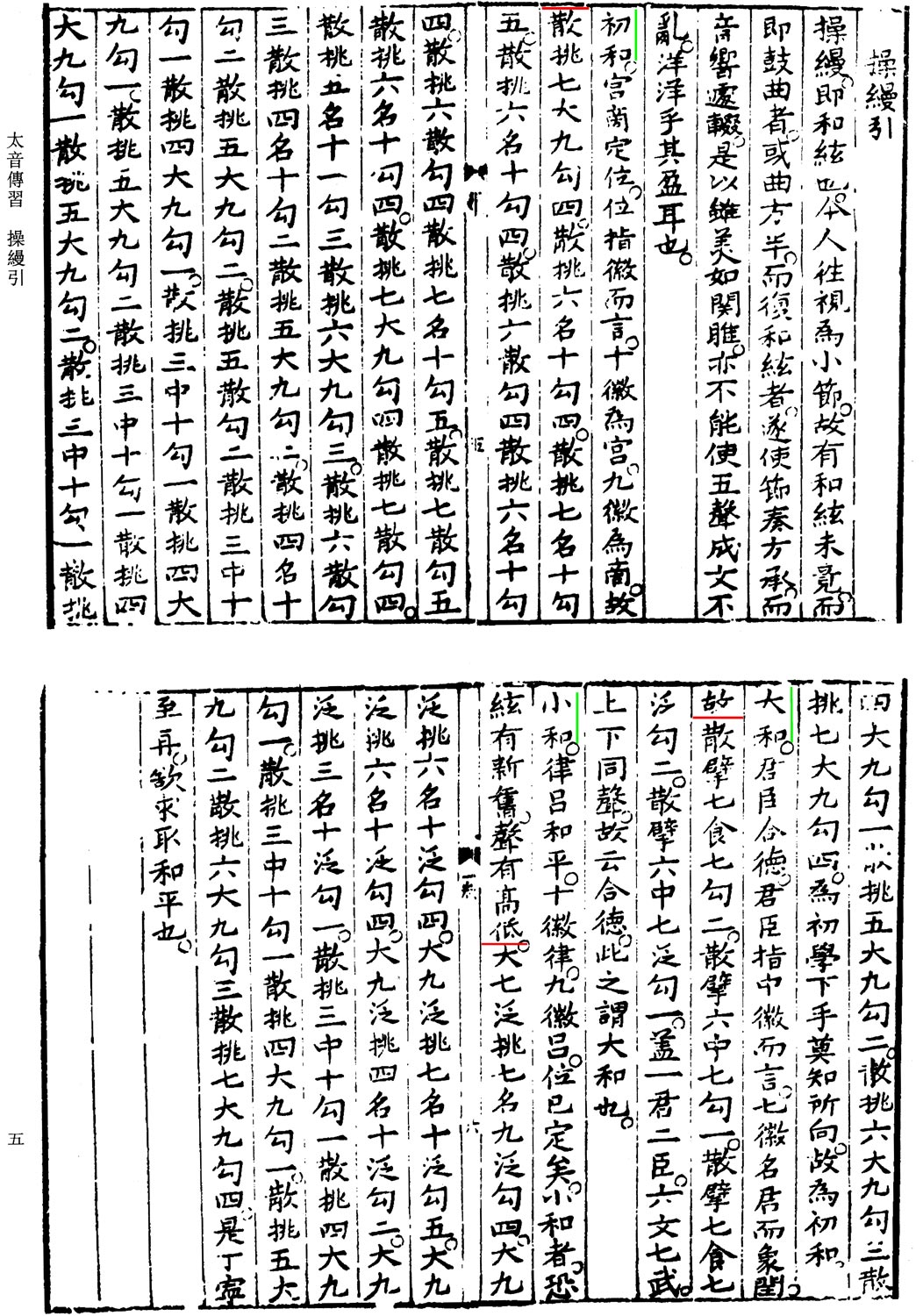

Called Caoman Yin, this version was written using longhand tablature (wenzipu); a typed version of the original (pdf is here together with my transcription. Longhand tablature was generally thought to have been completely replaced by the current shorthand tablature some time in the Tang dynasty. It has a short preface followed by a melody in three sections (details):

1557 Transcription

(pdf;

original)

This version, also called Caoman Yin and without lyrics, has an extended general preface, plus more detailed prefaces for each of the three sections.12 The general preface clearly identifies this as a beginners' melody; it also mentions "xianweng", using it as an honorific for a Daoist encountered in the Jiuhua Mountains (Anhui?).13 Xianweng, as mentioned above, was one of the nicknames for the famous Song dynasty recluse Chen Tuan, and the lyrics of later versions all mention Chen Tuan along with Xianweng. Here, although the writer addresses the Daoist as "xianweng", the Daoist identifies himself as the "Woodcutter of Jiuhua Mountains". The woodcutter plays the melody there transcribed, attributing it to a Warring States period music master named Shi Cao;14 according to tradition, when Shi Cao played the qin immortals would come to listen. Each section also has a statement attributed to this Woodcutter of Jiuhua Mountain. The titles of the three sections are the same as those in 1552 (see above):

Also in the 1573 edition (facs/41), this is the first surviving version with lyrics. It has no overall title, but each of the three sections is titled and has a short commentary.15 The short commentaries do not mention either name, but the lyrics invoke both Xianweng and Chen Tuan in a way that suggests they are the same person.16 Because in 1585 the lyrics are not in the melody section, Zha's Guide does not include them until

1596, where they are listed as three separate melodies. The sections/melodies are named:

One section; no commentary; Sino-Japanese pronunciation; listen with video from Japanese garden

Original 1557 Preface

The 1552 general preface, and the commentary with each section, are given below

(see in Chinese; my transcription is

above). However, since its preface is only the central section of the 1557 General Preface, and its commentary with each section is shorter, the more detailed 1557 prefaces are translated here.24

Furthermore, Cao Man is actually Harmonizing the Strings (i.e., tuning the strings). Nowadays people regard this as a minor detail. As a result they may begin playing before their string harmonization is not as good as it should be, or as they play a melody, perhaps they get halfway through, and they have to go back to harmonizing the strings. Thereupon they cause the rhythms to be abruptly disconnected, and the musical flow suddenly to stop. Then even if it is a piece as beautiful as

Guan Ju, they cannot cause the five tones to become elegant and not disorganized, or have a resonant fullness (洋洋乎) fill the ears.

Melody

The earliest four versions (1552, 1557,

1585 and 1589) have all been transcribed and recorded.29 1552 see above uses much the same lyrics as later versions; 1557 see above has no lyrics. The 1589 version is used as the soundtrack for a video from a Japanese garden because the Japanese version of the melody (see 1676) is identical to that in 1589.

Listen on ![]() .

The lyrics there and in other versions include the following names or expressions:

.

The lyrics there and in other versions include the following names or expressions:

陳摶 Chen Tuan (Proper name of Chen Tuan)

陳希夷 Chen Xiyi (Nickname of Chen Tuan)

得道 de Dao (Achieved the Dao)

的那 dena ("of that", filler syllables with no meaning)

![]() Watch video dubbed onto a camera shot panning the Rock Garden at Ryoanji Temple, Kyoto

Watch video dubbed onto a camera shot panning the Rock Garden at Ryoanji Temple, Kyoto

Transcription; no commentary; lyrics (not sung on video) are,

得道陳摶仙翁,得道陳摶仙翁,

得道陳摶仙翁,得道陳摶仙翁,

得道仙翁,得道仙翁,

得道仙翁,得道仙翁,

陳希夷得道仙翁,

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

The title could also suggest "操 playing 縵 around" on (a couple of) strings, implying here that they produce the same note and thus the title could be translated as "Adjust the Strings Prelude". The term Caoman is found in at least two ancient sources. In a passage in the Book of Rites it seems to mean "adjust the strings"; in other sources it seems to mean simply "play on the silk strings" (e.g., this poem by Fan Zhongyan). Both translations suggest this as the title of an essential beginner's melody.

(《禮記.學記》)不學操縵,不能安絃。(注)操縵,雜弄。(疏)言,人將學琴瑟若不先學調絃雜弄,則手指不便。手指不便,則不能安正其絃。先學雜弄,然後音曲乃成也。(嵇康,《酒會詩》)操縵清商,遊心大象。

The Book of Rites, Record of Learning says: “If one does not learn to adjust the strings (cao man), then one cannot proceed with the strings in order.”

(Commentary:) "Cao man" means "zanong": do various types of preparation.

(Sub-commentary:) This means: when a person is about to study the qin or se, if they do not first learn to play using various types of preparation with the strings, then their fingers will not move smoothly. If the fingers do not move smoothly, then the strings will not be in proper order. So one must first do this zanong, then the melodies can be played properly.

(Xi Kang, Wine Party Poem): “Do caoman in qingshang mode and the mind will roam in the Great Image (the Dao).”

(Return)

| 2. Chen Tuan (陳摶 906 [some sources say 871!] - 989) | Two images of Chen Tuan |

There is no actual evidence directly connecting Chen Tuan with the guqin or any of its melodies. Likewise, "仙翁 xianweng", as mentioned under under Xianweng Cao, does not seem elsewhere to be applied to Chen Tuan. Nevertheless, Chen Tuan himself does make a very interesting study.

There is no actual evidence directly connecting Chen Tuan with the guqin or any of its melodies. Likewise, "仙翁 xianweng", as mentioned under under Xianweng Cao, does not seem elsewhere to be applied to Chen Tuan. Nevertheless, Chen Tuan himself does make a very interesting study.

Chen Tuan (42618.1012; also .1013, but no mention of 仙翁 xianweng) had the style name 圖南 Tunan, self-nicknamed 扶搖子 Fu Yaozi. He was also called 陳希夷 Chen Xiyi (as mentioned in the lyrics here), referring to the title Master of the Inaudible and Invisible, bestowed upon him in 984 (希夷先生 Xiyi Xiansheng; 9025.26 希夷 xiyi: 無聲曰希,無色曰夷,為道之本體也。 Xi is what cannot be heard; yi is what cannot be seen. The name thus refers to the basic structure of the Dao. It also suggests longevity, hence 希夷﹕靈芝也 a longevity plant, perhaps a phantasmagoric mushroom.

Sources of information on Chen Tuan include the following. To my knowledge none of these mentions Chen Tuan's connection to the qin. In addition, I have not learned enough to comment on the reputed origins of the techniques attributed to Chen Tuan.

Louis Komjathy's book, Chapter 3, pp. 161-62, has the following poem, which is the closest I have seen so far of anything connected to the qin and said to be from Chen Tuan directly, though from the style it also seems quite possible that this was actually written much later (translation my own):

答太宗 (一)

九重特降紫泥宜,才拙探居樂靜綠。

Responding to the Taizong (Emperor), (I)

From the ninth layer of heaven came your decree sealed with purple clay;

As for the other three books, Livia Kohn's was formerly online. The latter two I have not seen, though apparently Volume I of Ni Hua-ching's book concerns "Kou Hong", a rather strange romanization of Ge Hong.

Beyond this there currently is a brief note on Chen Tuan in

Wikipedia. And

Feng Menglong wrote a story about him in 喻世明言 Yushi Mingyan (translated, see Story 14: Chen Xiyi Rejects Four Appointments....; pp.240-251).

The upper of the two illustrations at right comes from an edition of Chen Tuan's biography in Lie Xian Quan Zhuan. Chen Tuan is said to have been originally from 真源 Zhenyuan (now in eastern Henan province), also the reputed birthplace of Laozi. He may have studied to become an official during the Later Tang dynasty (923-935) but apparently spent much of this time wandering amongst various mountains, finally becoming a recluse at 華山 Hua Shan, a famous mountain range east of modern Xi'an. History records that at least three times, in 956, 976 and 984, he visited the Later Zhou and Song court in Kaifeng. During the 984 visit he was given the title mentioned above, Master of the Inaudible and Invisible. His writings are said to have been influential in the development of Neo-Confucianism, but he is most famously associated with Daoism. A poem attributed to him, Returning to My Retreat, is included in Red Pine (trans.), Poems of the Masters, Port Townsend, Copper Canyon Press, 2003; p.458.

Meanwhile, the lower image at right of Chen Tuan sleeping (compare

uncovered with covered) was taken in a grotto dedicated to Chen Tuan at the Jade Spring Temple (玉泉院 or 玉泉廟) by the north entrance to the Hua Shan park district. This temple also has a stone inscription of the text of Qingjing Jing, illustrations of Chen Tuan flying on a crane and of

Mao Nü playing the qin (but not of Chen Tuan playing the qin), and more recently a giant outdoor statue of Chen Tuan sleeping (location uncertain: image).

Further regarding sleep, Chen Tuan's reputed skill at this has been related in various Daoist legends. The bottom image at right of showing a black statue of Chen Tuan sleeping under a quilt is testament to this. As the legends, these were already forming during his lifetime. He was particularly famous for meditation, and so his ability to sleep became related to meditation: other images, such as the one above, come from books said to have preserved his "sleeping gongfu" (睡功 shui gong). These are all discussed in English in the works listed above, none of which seems to mention guqin.

Because the qin music is often observed to be music so calming that it puts listeners to sleep, it is fun to speculate as to whether this is the reason Chen Tuan came to be connected to the qin. Nevertheless, as mentioned above, until centuries after Chen Tuan's passing there seems to be no evidence connecting him in any way with the qin. Specifically, there is nowhere any suggestion that Chen Tuan himself ever wrote about the qin, much less played or listened to it.

On the other hand, in addition to his seemingly being honored by the lyrics of the melodies variously called Caoman Yin and Xianweng Cao, he has also been associated with at least two other melodies:

Chen Tuan and "internal arts" such as Liuhe Bafa (六合八法)

This does not prove that they were not ancient terms or that they do not describe ancient practices, only that the editors presumably did not find the terms used within ancient literati culture.

Popular culture associates Chen Tuan (Chen Xiyi) with "Life Energy Cultivation (氣功 qigong; Wiki), more specifically with a number of internal arts (內功 neigong; again Wiki). Some stories even say he founded an internal Chinese martial arts form called Liuhe Bafa (Six Harmonies Eight Methods), also known as Shui Quan (Water Boxing, see also in Wikipedia). Classical dictionary references do not give sources for either 六合八法 Liu He Ba Fa (1477.168 only 六合 liuhe) or Water Boxing (水拳 Shui Quan 17458.xxx). The connection with Chen Tuan is through a legend of uncertain origin that centuries after Chen's death a 李東風 Li Dongfeng (East-wind Li, Bio/xxx) learned Hua Mountain Taiji Quan (華岳太極拳 Hua-Yue Taijiquan) from now-lost texts Chen had left behind, then wrote down its principles in the form of a 134-line mnemonic formula (訣 jue, often rhymed). Each verse consists of five-characters, and this Liuhe Bafa Five-character Formula (六合八法五字訣 Liuhe Bafa Wuzi Jue, q.v.), with its teachings, are said then to have passed down through 宋元通 Song Yuantong, then various other people, spreading out and forming the basis of the modern 六合八法 Liuhe Bafa martial arts system. None of the early names other than Chen Tuan is in historical dictionaries, and from looking at the original verses and at modern translations, e.g., by

Paul Dillon, with commentary, I have not found out a date or source for the story making the connection to Chen Xiyi, nor have I found any connection to guqin. (Thanks to K. Conor Foxx for advice; he has also done a translation.)

3.

Tuning and mode: 5 6 1 2 3 5 6 and/or 1 2 4 5 6 1 2

Mode is determined by which notes are tonal centers: in this regard the xianweng/caoman melodies are somewhat complicated as the tonal centers could be considered as changing. For this compare the first half and second half of the Xianweng Cao transcription.

山色滿庭供畫障,松聲萬壑即琴絃。

無心享祿登台鼎,有意求仙到洞天。

軒冕浮榮絕念慮,三峰只乞睡千年。

but I, with talent gone, from my remote dwelling seek only to enjoy peace and greenery.

The mountain colors fill my courtyard like painted folding screens;

the sound of pines from ten thousand gullies is actually music from zither strings.

I have no heart for enjoying official glory or ascending the ranks of power;

my intent is only to seek immortality in the grotto-heavens.

Carriages, fancy caps and fleeting glory have been cut out of my thoughts,

And amidst the Three Peaks (of Mount Hua) I ask only for a thousand year-long sleep.

The sound of Chen Tuan's sleeping was sometimes said to be a "Huaxu melody", and a qin melody of this name is included amongst the "most ancient" pieces in the Shen Qi Mi Pu (1425 CE; I/118), but as yet there seems to be no information to show how Chen Tuan became connected it.

This song in eight sections survives only in Taiyin Xisheng (1625; IX/174). The preface there says Chen Tuan composed it out of grief that there were no sages for their society in decline. The lyrics begin: 物之生於天地兮,何曾有盡藏。鱗之瑞兮,吾知其龍章....

Chen Tuan's connection to these may be through his commentary on the 易經 Yi Jing. In fact, there is a lot of information on the internet about what might be generally referred to as "internal arts", but there is little historical detail. ZWDCD and HYDCD usually try to give the most ancient references to any terms they define, but here they have none:

(Return)

In this number notation system the numbers indicate relative pitch. Thus, 1=do, 2=re, etc. By tradition the Chinese pentatonic scale is 1 2 3 5 6 and tuning the seven qin strings follows this standard; and in my transcriptions do is written as "c", but the exact pitch depends on such things as the size and quality of the instrument and strings.

(Return)

| 4. Caoman Yin in longhand tablature (see details) | typed text with transcription |

There are two recordings, "Bb" has the first string tuned to Bb,

"A" has the firs string tuned to A. As for details of longhand tablature, see the earliest example.

There are two recordings, "Bb" has the first string tuned to Bb,

"A" has the firs string tuned to A. As for details of longhand tablature, see the earliest example.

Longhand versions of Cao Man Yin are included in at least five handbooks, all but 1670 virtually identical (titles link to further comment in the chart):

- Taiyin Chuanxi (1552; QQJC IV/5; the version linked at right and transcribed here)

- Wenhui Tang Qinpu (1596;

QQJC VI/172).

- Yangchun Tang Qinpu (1611; QQJC VII/252)

- Qinyuan Xinchuan Quanbian (1670; QQJC XI/300)

- Yingyang Qinpu (1751; QQJC XVI/48)

The modern shorthand tablature, outlined here, is said to have developed from longhand tablature during the Tang dynasty. As yet there do not seem to be any studies into whether these longhand examples from the Ming dynasty are evidence of antiquity, or evidence of attempts to forge antiquity. The only authenticated surviving melody using longhand tablature is Jieshidiao You Lan.

Thus, although this use of longhand tablature could suggest great antiquity for this melody, more likely it is just a simple way to introduce students to the meaning of the shorthand tablature they would be seeing for the qin; in other words only for pedagogical purposes.

(Return)

5.

1585 Caoman Yin (See also the tracing chart below.)

The version here has been edited (see circles) to be better structured and more complete.

(Return)

6.

Other famous Daoist recluses referred to as "Xianweng"

仙翁 Xian Weng is often translated as "Immortal elder".

Some of the famous early names associated with this nickname include:

- 董奉仙翁 Dong Feng (physician; ca.200-280; Wiki)

- 葛洪仙翁 Ge Hong, 283–343)

- 呂洞賓仙翁 Lu Dongbin (Tang dynasty)

For other references, e.g., in poetry, see here.

(Return)

7.

操縵引 Caoman Yin to 仙翁操 Xianweng Cao (See also the tracing chart below.)

Comparing these two is somewhat complicated by the fact that recently there has been a tendency to refer to modern descendants of Caoman Yin as Xianweng Cao. In general I refer to these two as I originally learned them, as can be distinguished by looking at my online transcriptions:

- Xianweng Cao transcription (largely as learned from Sun Yü-Ch'in)

- Caoman Yin transcription, page 1 (my reconstruction of the version published in 1585)

Althouth there is a clear relationship between the lyrics of the early Caoman Yin and those of the Xianweng Cao transcribed above, and there are also melodic similarities, the differences suggest that this Xianweng Cao did not simply grow out of Caoman Yin. And although a recognizable form of this Xianweng Cao may date back to the 19th century, from my brief examination of all available handbooks I have not been able to find any specific evidence for this.

There is some further information on the source of that version

here.

(Return)

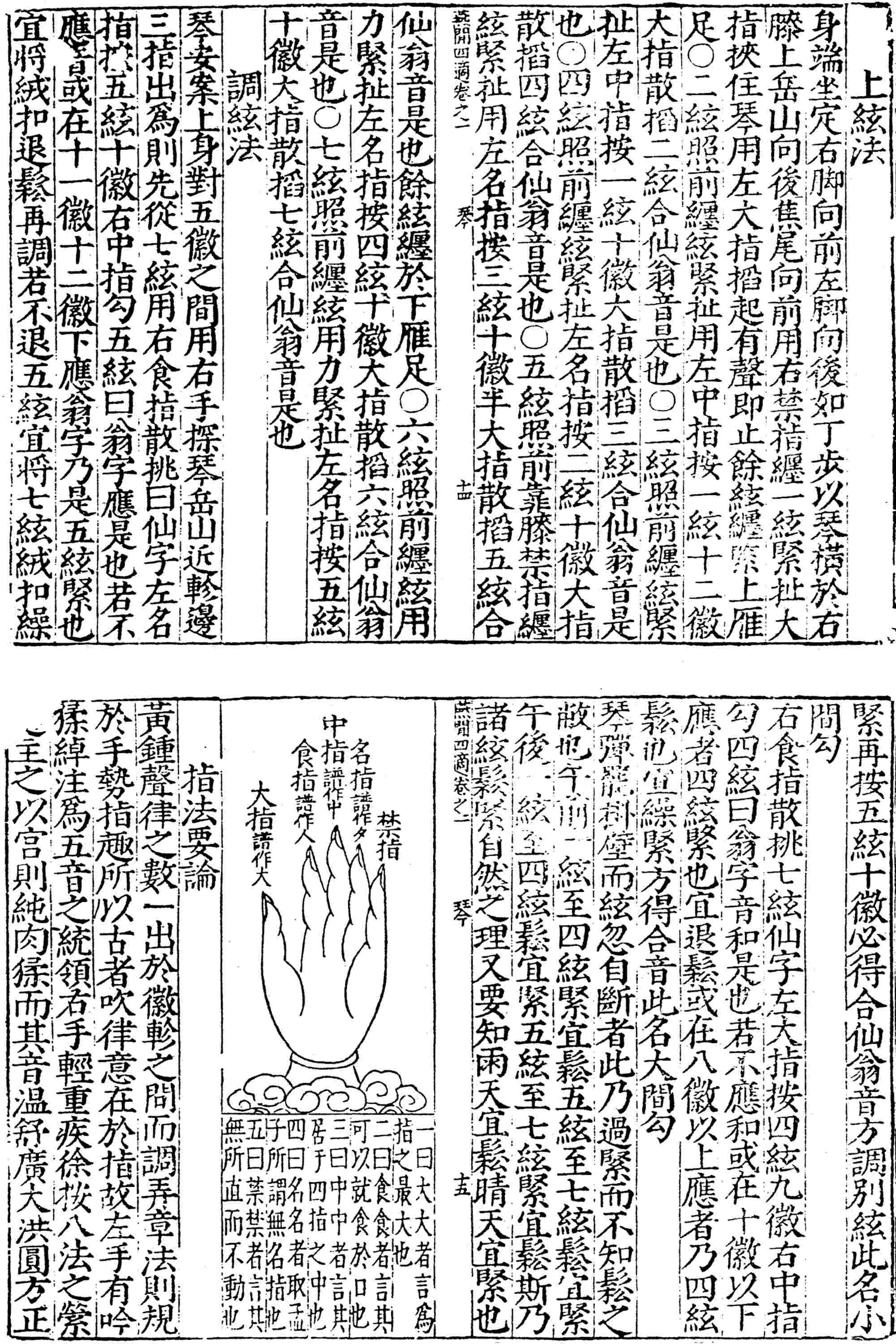

| 8. Xian-weng Sound (仙翁音 Xian-weng Yin) | From 琴適 Qin Shi, 1611 (VIII/14) |

Here xian-weng is hyphenated because the two characters seem to refer to two different types of qin-playing intervals: "xian" refers to an open string note while "weng" refers to the same note played on a stopped string. In what might be called "xian-weng melodies" the words "xian" and "weng" may be sung while playing them. The strings played may have one string in between (e.g., 7th string and 5th string), two strings in between (e.g., 6th and 3rd strings), and so forth.

Here xian-weng is hyphenated because the two characters seem to refer to two different types of qin-playing intervals: "xian" refers to an open string note while "weng" refers to the same note played on a stopped string. In what might be called "xian-weng melodies" the words "xian" and "weng" may be sung while playing them. The strings played may have one string in between (e.g., 7th string and 5th string), two strings in between (e.g., 6th and 3rd strings), and so forth.

The earliest example I have so far found of the use of this terminolody is in two connected sections of 琴適 Qin Shi (1611; see QQJC VIII/14). These are, in order,

- "上絃法 Shang Xian Fa" (Method of stringing a qin; see at right; expand).

(Comment: After briefly describing how physically to install and tune the strings, this passage seems to give tablature for playing a series of two notes in which the first of each is an open string ("xian") and the second is a stopped string with the same pitch ("weng"); together these are called "仙翁音 Xian-weng Yin", which otherwise would mean "the transcendent immortal's sounds".The text of the first two sections (first 5½ lines) at right are as follows (problems with this explanation can be seen by comparing it with, e.g., this illustration (I/51), where if anything the left foot is forward.)

"身端坐定,右脚向前,左脚向後。如丁步以琴橫於右膝上,岳山向後,焦尾向前。 用右禁指纏一絃緊,扯大指挾住琴。用左大指搯起,有聲即止。餘絃纏緊上雁足。

二絃照前纏絃緊扯。用左中指按一絃十二徽,大指散搯二絃合。仙翁音是也。...."With body upright sit steady, with the right foot forward and the left foot back. With the feet “aligned in a T-shaped” (? 丁步), rest the qin across the right knee (both knees?), with the yueshan (bridge) to the back and the jiaowei (tail) to the front. Use the right "forbidden finger" (baby finger) to wind the first string tightly(around a goose foot), pulling it tight and fixing it while pressing it against the qin with the thumb. With the left thumb, pluck it upward — if it makes a sound, then stop. The remaining strings are each wound tight in the same manner onto their goose-feet tuning posts.

The second string in the same way as the first is then wound and pulled tight. Use the left middle finger placed at the twelfth hui on the first string, and the (left?) thumb to pluck the open second string. This is the xian-weng sound (same note on one open and one stopped string)...."The translation is very tentative; again see this illustration.

- "調絃法 Tiao Xian Fa" (from here; VIII/14); more in this list below; also see image at right;

expand)

This seems to explain how to do this tuning by tightening and loosening strings, adding that plucking the open string with the right hand creates sound "仙 xian" then playing the unison on a stopped lower string creates the sound "翁 weng".The text there is as follows, again with a tentative translation:

"琴安案上,身對五徽之間,用右手探琴岳山近軫邊三指出爲則。 先從七絃用右食指散挑曰仙字,左名指按五絃十徽,右中指勾五絃,曰翁字應是也。 若不應音,或在十一徽、十二徽下應翁字,乃是五絃緊也,宜將絨扣退鬆再調。若不退五絃,宜將七絃絨扣繰緊,再按五絃十徽,必得合仙翁音,方調别絃。此名小間勾。

右食指散挑七絃仙字,左大指按四絃九徽,右中指勾四絃,曰翁字,音和是也。若不應和,或在十徽以下應者,四絃緊也,宜退鬆;或在八徽以上應者,乃四絃鬆也,宜繰緊,方得合音。此名大間勾。Place the qin flat on a table, with your body facing the area around the fifth hui (the middle position on the surface). With the right hand, extend the three fingers toward the yueshan (near the tuning pegs), to be the reference. Begin from the seventh string: use the right index finger to 散挑 pluck the open string. This is called the “Xian” note (仙字). Then press the fifth string at the tenth hui with the left ring finger; pluck the fifth string with the right middle finger. This is called the “weng” note (翁字). If the two correspond, then it is correct. If they do not match, and the “weng” note appears at the eleventh or twelfth hui, then the fifth string is too tight; loosen its silk cord winding at the peg and adjust again. If loosening does not correct it, then tighten the seventh string’s winding. When pressing the fifth string at the tenth hui produces a note matching the seventh string open (仙–翁), only then can you proceed to tune the other strings. This (situation where the xian-weng sound is from two strings that have one in between) is called the “small interval gou” (小間勾) method.

Next: use the right index finger to pluck the seventh string open (仙字); press the fourth string at the ninth hui with the left thumb, and pluck the fourth string with the right middle finger. This makes this the “Weng” note. If the two are in harmony, then it is correct. If they do not harmonize — if the “Weng” note appears below the tenth hui, the fourth string is too tight and should be loosened; if it appears above the eighth hui, then the fourth string is too loose and should be tightened. Only when the tones match is the tuning correct. This (situation where the xian-weng sound is from two strings that have two strings in between) is called the “large interval gou” (大間勾) method.

Again not yet fully translated; however, the ideas seem to come from 禮記,學記

See also the further discussion here.

Some earlier handbooks seem to have similar explanations but without using the words "xian" and/or "weng" (e.g., see 1596#1).

These explanations are clearly connected to the what is conveyed by the melodies discussed here. And although they came in several forms, all (as with my video) feature many passages pairing the same note played on an open string and a stopped string, as well as two harmonics playing the same note on two separate strings. At one time these melodies were more commonly referred to by other names. However, the surviving lyrics have almost always mentioned Chen Tuan by name.

Finally, although this "xianweng" technique does seem to connect to the Transcendent Immortal melodies (仙翁操 Xian Weng Cao) that became popular for beginners, as yet I have not seen any that pre-date the earliest xian weng or cao man melodies. Thus the source of the connection between the melodies and either Chen Tuan or the xian weng technique remains a mystery.

(Return)

9.

Centering through repetition

The technique of playing a simple melody (or even a simple note pattern) repeatedly in order to settle down or center oneself before playing might be considered as an aid to meditation: do it until the mind is empty while playing. This is in some ways comparable to the old custom of Chinese calligraphers rubbing their own ink. To do this they add water to the inkstone, then rub with another stone. To get in the right mood they might at times spend a considerably longer time than necessary doing this before beginning to write.

Regarding "prior to playing", it might be noted that old handbooks always placed the tablature for Caoman Yin among introductory essays, not together with the other melodies.

(Return)

10.

Sleeping meditation

Chen Tuan's "sleep exercises" (睡功 shuigong) are discussed by Louis Komjathy in Traces of a Daoist Immortal (2024; follow this link).

The text with the image above is the following poem (translation from Komjathy),

The lung qi extends to dwell in the position of Kǎn-water,

The liver qi retreats to reside in the palace of Lí-fire.

脾氣呼來中位合,五氣朝元入太空。

Circulate qi while exhaling to harmonize the center,

The Five Energies assemble at the Origin to enter great emptiness.

See Komjathy for further explanation.

Guqin and sleep

11.

Section titles from 1552 and commentary from 1557

The section titles with the 1552 version are 初和 Chu He; 大和 Da He; 小和 Xiao He. The commentary is here, with translation.

Although the 1557 handbook seems to have been published later, there is no clear indication proving that the text of the 1552 preface is older.

12.

1557 version

13.

Woodcutter of Jiuhua Mountains 九華山樵

14.

衛人師曹 9129.xxx. Shi Cao's qin biography, 琴史琴補 Qin Shi Bu #16 says he was a music master in the court of Duke Ling of Wei. It does not mention Xianweng Cao, but says that whenever Shi Cao played many immortals would gather. Shi Cao is also mentioned in some of the later prefaces to Caoman Yin.

15.

1585 Section Titles and Commentary

16.

The lyrics are mostly as follows:

However, the second section of this handbook also inserts the lyrics of a song beginning "Summer goes, winter comes, spring turns to autumn....". These lyrics also accompany one section of the qin melody Xing Tan (#34 of Xilutang Qintong, 1525).

17.

Tracing 操縵引 Caoman Yin (and 仙翁操 Xianweng Cao; also see chart)

Because of the incomplete nature of his listings of these, making the chart below required looking through the introducturoy essays to find them; often not included in the Table of Contents may make them relatively easy to miss

By looking directly at the handbooks for the various versions and titles I have found 17 entries up to 1802. More details will be added once I have examined the 30-volume edition of Qinqu Jicheng published in 2011; the pagination used here follows that edition.

The version I learned of

18. Tuning Method (調絃法 Tiaoxian Fa): tuning essays that mention 仙翁(音)

Xian Weng (Yin)

Most likely these are also in other handbooks as well; e.g., see also next footnote.

19.

Xianweng method (仙翁法 Xianweng Fa)

20.

Play Xianweng's Song (調仙翁歌 Tiao Xianweng Ge)

This is discussed further under Xianweng Cao, but I have not yet examined these Tiao Xianweng Ge well enough to know if any of them forms a link between the older Caoman Yin and the Xianweng Cao melody that I learned from Sun Yü-ch'in.

21.

Published versions of 仙翁操 Xianweng Cao

Sun Yü-ch'in did not sing the lyrics when he taught Xianweng Cao, but I remember seeing them at that time. He did give me some tablature, but always said we should copy him, not look at tablature. The tablature of Xianweng Cao I have from Taiwan has number notation underneath but no lyrics. It is very similar to the version in Yinyinshi Qinpu, but it has no lyrics. For my own transcription into staff notation I added the lyrics from memory, then later checked it with the version in Yinyinshi Qinpu.

22.

The preface in this 1557 version says this as follows.

23.

He actually said this in connection with the melody

Xiang Fei Yuan, played today very much as it is written in Taigu Yiyin (1511). Taigu Yiyin has many simple songs. At that time there was apparently debate about singing style vs. purely instrumental style, but I haven't found specific details about this. One can imagine that the debate involved the relative value of a simple style vs. a complex one, but again I have not found the details.

Xianweng Cao, one to two minutes long, begins and ends on the same two notes. This naturally allows one to play the melody over and over. Such repetition can be settling. It also allows the player to focus on the subtle tones that can be produced by a silk string qin when played well. This is the essence of qin play.

This technique for settling down before playing is also in some ways comparable to the old custom of Chinese calligraphers rubbing their own ink. To do this they add water to the inkstone, then rub with another stone. To get in the right mood they might at times spend a considerably longer time than necessary doing this before beginning to write.

The repetitions of the modern Xianweng Cao seem more orderly than those of the old versions of Caoman Yin, making this meditative approach easier.

24.

杏莊太音補遺操縵引 Cao Man Yin of Xingzhuang Taiyin Buyi (1557, III/311)

25.

Original General Preface of 1557 (III/311)

今之老子琴者,固無需子是。然而初學之士,歖求其琴全,含是其奚取哉?鳴呼。學者少而習之老而不知,則其于琴可如矣。

26.

(I.) 初和,宮商定位 (Beginning Harmony; the notes are fixed)

27.

(II.) 大和,君臣合德 (Great Harmony, Master and vassal have virtues in harmony)

28.

(III.) 小和,律呂和平 (Small Harmony, The notes are harmonious)

29.

Cao Man Yin from 1552 (see details)

Unless otherwise indicated, all are grouped with essays, not with melodies

The above chart probably has some omissions, but as far as I can tell none of the handbooks in Qinqu Jicheng called the melody Xianweng Cao or had a version more closely related to the version I originally learned than to the old Caoman Yin. For more on this see also Published versions of Xianweng Cao.

That was 134+4 five-character phrases. There is also a different set of 134 five-character phrases beginning as follows (complete text and translation at

www.bartholomy.ooo/).

In traditional literature there is little or nothing directly connecting qin play with sleep, but there is much written about its calming effects. Here are some quotes:

(Return)

(Return)

See translation above. The titles are the same as those of the 1552 version, but each section also has a subtitle.

(Return)

173.469 identifies 九華 Jiuhua as the name of mountains in Anhui and near the coast in Fujian. The more famous of these is the 九華山 Jiuhua Mountains northwest of Huangshan in Anhui province and sacred to Buddhists. I have found nothing to link this name or these places with Chen Tuan, who is instead associated with 華山 Hua Shan (31910.7/6 makes no mention of the number 9).

(Return)

(Return)

The section titles and commentary with the 1585 version are as follows:

西峰曰,其法今只知云和琴而是不知法則也。子法定音和畢再從容於七絃從順鼓撫聲音次第輪環發揮自然入妙喜音者聽吾和聲美亦無窮矣。

法從七徽起(?走+尺)順輪鼓撫下九徽亦接順撫又下十十二次第依法和弄是也。

No commentary at the beginning, but the end suggests that one should use the above to fix the mind and calm the spirit:

已前隨應循環調撫音定心靜神清而起意。

(Return)

得道陳摶仙翁 De Dao Chen Tuan Xianweng (Chen Tuan ….)

陳摶仙翁 Chen Tuan Xianweng

(Return)

Zha Fuxi's Index is very much incomplete on these introductory/warmup melodies, presumably because they are almost always included in the introductory sections of handbooks, not with the listed melodies. His entries are as follows:

(Return)

See also above. This is a not-uncommon type of essay in early qin handbooks. I have not yet studied them carefully, but a number of them include instructions together with the name Ancient Immortal ("仙翁 Xianweng"), the term 仙翁音 Xianweng yin (Xianweng sound; see further), or the words "仙 xian" and "翁 weng" separately

(also see further). Examples include:

1.

琴適

(1611; VIII/14)Introduces the 仙翁音 Xianweng Sound: sections called 上絃法 Shang Xian Fa and 調絃法 Tiao Xian Fa explain tuning using the words 仙 xian and 翁 weng both separately and together. This is not in 1597 and neither handbook has the tuning melody.

2.

五知齋琴譜

(1722; XIV/392)調絃法 Tiaoxian Fa: does not seem to be an actual melody (compare 1802, 1864, etc.):

Commentary is mixed with longhand tablature, with "仙翁 Xianweng" at the end of many phrases

3.

自遠堂琴譜

(1802; XVII/296)From the third last line of p. 296 through p. 298 there is what seems to be an untitled longhand tuning exercise or test using the words 仙 xian and 翁

weng; from last line of top half of p.297 compare 1722

4.

琴學尊聞

(1864; XXIV/219)Untitled essay on tuning, beginning p. 218, mentions 仙 xian and 翁 weng

compare 17225.

琴學入門

(1864; XXIV/283)The essay 調和絃法 Tiaohe Xian Fa mentions 仙 xian and 翁 weng

See previous

6.

琴瑟合譜

(1870; XXVI/142)調絃法 Tiaoxian Fa is like earlier essays mentioning 仙 xian and 翁 weng (also in 琴府 Qin Fu)

See previous

7.

琴學初津

(1894; XXVIII/240)調絃歌 Tiaoxian Ge

Compare previous

(Return)

See, e.g., in Meian Qinpu (XXIX/196) and compare with Xianweng sound.

(Return)

See Qinxue Lianyao, Folio I, p.23 (XVIII/85; see 1739 below). The piece begins like the end of the version of Xianweng Cao that I learned, then has some phrases from the earlier versions.

(Return)

There are two versions of Xianweng Cao in 愔愔室琴譜 Yinyinshi Qinpu (2000), the handbook of 蔡德允 Tsar Teh-yun (Cai Deyun); neither version has any commentary.

(Return)

(Return)

(Return)

The melody of the 1557 Taiyin Buyi, like its commentary, is somewhat more elaborate than that of the 1552 Taiyin Chuanxi. The 1552 handbook is attributed to 李仁

Li Ren, who called himself Friend of Mounatins (友山 You Shan). Li is said to have brought melodies with him from Beijing to Nanjing. Taiyin Chuanxi has a close relationship with Xingzhuang Taiyin Buyi, compiled by 蕭鸞 Xiao Luan, who was from Henan.

(Return)

The original 1557 preface, translated above was undivided; here it is divided into three paragraphs. The 1552 preface consists of only the middle paragraph (minus the first character, 然). The original Chinese from 1557 is as follows:

The original 1557 afterford, also translated above, is as follows,

(Return)

The original Chinese is as follows:

(Return)

The original Chinese is as follows:

(Return)

The original Chinese is as follows:

(Return)

The 1552 melody can be described as follows:

(Return)

Return to top; go to Learning to play qin

or the Guqin ToC.

Appendix 1

Chart tracing 操縵引 Caoman Yin (and 仙翁操 Xianweng Cao)

(see comment as well as

Tuning Method [調絃法 Tiaoxian Fa: essays that mention Xian Weng

琴譜

(year; QQJC Vol/page)

Further information

(QQJC = 琴曲集成

Qinqu Jicheng; QF = 琴府

Qin Fu)

__. 西麓堂琴統

(1525;

III/62)調絃品 Tiaoxian Pin; no connection to Tiaoxian Runong: related only to 1539; 2 sections; no commentary

no lyrics, no mention of Xianweng; title occurs only here; 1st piece; mode not mentioned

__. 風宣玄品

(1539;

II/83)一撒金 Yi Sa Jin; related only to 1525; 2 sections; no commentary;

lyrics have no mention of Xianweng;

title occurs only here; 7th piece; grouped with gong mode melodies

1. 太音傳習

(1552;

IV/5)操縵引: 初和, 大和, 小和; Caoman Yin, in three parts: Chu He, Da He (in harmonics) and Xiao He; earliest, and in 文字譜 longhand tablature

short preface does not mention Xianweng; related to next, but simpler; no lyrics;

original /

transcription

2. 太音補遺

(1557;

III/311)操縵引: 初和, 大和, 小和; Caoman Yin, music in same three parts (see

transcription), but longer; no lyrics;

long preface mentions Xianweng and says the piece is by(衛)師曹公 Shi Cao of Wei: his bio says whenever he played immortals would come. Musically related to the other Caoman Yin.

original /

transcription

. 新刊正文對音捷要

(1573; at front)Not indexed; see next

3. 重修真傳琴譜

(1585;

IV/303)調絃入弄, 泛音調弄, 五徽調弄 Tiaoxian Runong, Fanyin Tiaonong (harmonics), Wuhui Tiaonong (no overall title; no connection to

1525); commentary before and after; lyrics all begin and repeat "得道仙翁....得道陳摶仙翁 (Transcendent immortal Chen Tuan who attained the Dao)", but adds a song

(lyrics) at the end of #2

(transcription)

4a.

真傳正宗琴譜

(1589;

VII/58)調絃入弄 Tiaoxian Runong with lyrics; one section

(badly printed; compare 1676)

4b. 真傳正宗琴譜

(1609; Facs.)Presumably identical to 1589

5a. 文會堂琴譜

(1596;

VI/175)Longhand 操縵引: 初和, 大和, 小和; line by line identical to 1552;

Followed by a 調絃 Tiao Xian with instructions on tuning by loosening and tightening strings to play unisons

5b. 文會堂琴譜

(1596;

VI/191)Titles, lyrics and tablature identical to 1585 but no commentary;

first three pieces in tablature section

6. 陽春堂琴經

(~1610;

VII/252)Caoman Yin, with Chu He, Da He and Xiao He; longhand tablature again line-by-line identical to 1552;

no lyrics; commentary doesn't mention Xianweng

7. 陽春堂琴譜

(1611#1;

VII/351)Caoman Yin, with Chu He, Da He and Xiao He;

Longhand; same as ~1610

. 琴適

1589(1611#2;

VIII/14)Introduces the Xian-weng Sound, with sections called 上絃法 Shang Xian Fa and 調絃法 Tiao Xian Fa (see further).

Not in 1597 and neither handbook has the tuning melody.

8. 理性元雅

(1618;

VIII/178)調五絃手以五二為主;調七絃手法以七四為主;調九絃手法以九六為主

3 pieces with Xianweng lyrics set for 5, 7 and 9 string qins, each a simple version of the melody

9. 古音正宗

(1634; IX/255)調絃入弄 Tiaoxian Runong: lyrics; one section; similar to first sections above, adding a short harmonic coda which has the first mention of 陳希夷 Chen Xiyi; no commentary; some modern recordings called Xianweng Cao seem quite similar to this.

10. 琴學心聲諧譜

(1664;

XII/49)調絃入弄 Tiao Xian Ru Nong (Xianweng lyrics)

11. 琴苑新傳全編

(1670;

XI/300)操縵引 Caoman Yin, as 1552: longhand tablature; no lyrics;

Begins the same as early longhand versions then seems quite different and seemingly abbreviated

12. 和文注音琴譜

(<1676; XII/167)調絃入弄 Tiaoxian Runong; tablature same as 1589 but adds Sino-Japanese pronunciation

Japan; above and also next

13a. 東皋琴譜

(1709;

XII/248)調絃入弄 Tiaoxian Runong

Japan; same as previous; see previous

13b. 東皋琴譜

(1772?;

XII/283)操縵引 Caoman Yin; compare previous

Japan; no lyrics; Zha Guide mentions it, saying "按即仙翁操或調絃入弄"

14a. 一峰園琴譜

(1709; XIII/494)古調絃法 Gu Diao Xianfa, one section + coda; Xianweng lyrics)

Introduction ("定絃法"); lyrics

14b. 一峰園琴譜

(1709; XIII/497)調絃散音 Tiaoxian Sanyin in two sections: 實音 Shiyin (stopped sounds) and 泛音 Fanyin (harmonics)

Introduction ("定絃法"); lyrics

15. 琴學正聲

(1715; XIV/35)初和 Chuhe, 大和 Dahe, 小和 Xiaohe; music like 1552; also no lyrics; intro somewhat different -- doesn't mention Xianweng, but attributes piece to Shi Cao of Wei.

16. 琴學練要

(1739; XVIII/85)調仙翁歌 Tiao Xianweng Ge; lyrics; one section; beginning is like the end of the modern version, then it uses some of the older phrases (facsimile edition is 治心齋琴譜)

17. 穎陽琴譜

(1751; XVI/48)操縵引 Caoman Yin; again longhand tablature; no lyrics; commentary, but doesn't mention Xianweng; seems to copy early versions but not line by line so a few differences.

18. 酣古齋琴譜

(n.d.; XVIII/436)調絃入弄 Tiaoxian Runong; 泛音調弄 Fanyin Tiaonong; lyrics

Placed at end of handbook!

19. 太和正音琴譜

(n.d.; XIX/9)調絃 Tiao xian; begins with longhand tablature (explanation?),

then (p.10) has melody in three sections similar to earlier versions (no lyrics)

20. 虞山李氏琴譜

(n.d.; XX/26)調絃入弄 Tiaoxian Runong; lyrics

Short melody (compare 1634 versions)

21. 琴學軔端

(1828; XX/391)調仙翁指南 Tiao Xianweng Zhinan

One section, no lyrics; reprint is difficult to read

22. 二香琴譜

(1833; XXIII/88)調絃入弄 Tiao Xian Runong

One section, no lyrics or commentary

23. 梅花仙館琴譜

(n.d.; XXII/9)調絃入弄 Tiaoxian Runong; short melody; no lyrics

XXII/22 has a second version, slightly different

24. 一經盧琴學

(1845; XXII/60)調絃法 Tiaoxian Fa; one section, no lyrics

25. 琴譜正律

(n.d.; XXIII/45)調絃入弄 Tiaoxian Runong

3 sections; lyrics; credits Yang Xifeng (Yang Biaozheng, compiler of Chongxiu Zhenchuan Qinpu; 1585); almost same as that version (q.v.)

26. 師白山房琴譜

(n.d.; XXIV/8)合絃仙翁調 Hexian Xianweng Diao and 仙翁泛音 Xianweng Fanyin (harmonics)

Similar to various Caoman Yin, but see last line of first piece

27. 青箱齋琴譜

(n.d.; XXIV/366-7)和絃 He Xian (lyrcs only on last phrase) and 泛音調弄 Fanyin Tiaonong (lyrics throughout)

調絃入弄 Tiaoxian Runong and 五徽調弄 Wuhui Tiaonong (only two: harmonic section seems tucked into #1; lyrics)

28. 枕經葄史山房雜抄

(n.d.; XXVII/83)調絃入弄 Tiaoxian Runong; 3 sections; lyrics; credits Yang Xifeng (Yang Biaozheng, compiler of Chongxiu Zhenchuan Qinpu; see 1585); also credits 諸城王冷泉 Wang Lengquan of Zhucheng (p. 82 has a related 和絃歌 Hexian Ge with gongche pu but no lyrics)

29. 雙琴書屋琴譜集成

(1884; XXVII/276)調絃入弄 Tiaoxian Runong; one section; first piece; attribution to Yang Biaozheng, compiler of Chongxiu Zhenchuan Qinpu (1585), but it has an elaborated version of the first section in that handbook (q.v.)

30. 琴學初津

(1894; XXVIII/241)和絃仙翁指法 Hexian Xianweng Zhifa, 泛和法 Fan He Fa and 演指仙翁吟 Yanzhi Xianweng Yin

The latter in particular, though still related to Caoman Yin, has more content; Xianweng lyrics; afterword

31. 琴學管見

(1930; XXIX/253)調絃入弄 Tiaoxian Runong; lyrics; one section; harmonic coda

Followed by the similar 得道歌 De Dao Ge

32. 愔愔室琴譜

(2000; pp. 10-11)Yinyinshi Qinpu has two melodies called 仙翁操 Xianweng Cao (lyrics but no commentary);

The first is related to this Xianweng Cao, the other to this Caoman Yin

33. ???

???This entry is being reserved for the as yet unlocated source of the version of Xianweng Cao that I originally learned. It is only vaguely connected (mainly through lyrics) to the Caoman Yin above. Existing modern copies that I have seen are arranged in one section, but could be considered as two. It is not in Meian Qinpu so is presumably not Meian school.

return to top

Appendix 2: Liuhe Bafa

Five-character Formula (六合八法五字訣 Liuhe Bafa Wuzi Jue)

虛靈含有物,原來自我始,兩腿似弓彎,彷彿臨大敵,形動如浴水,有法是虛無,釋家為圓覺,先從八法起,

收放勿露形,生疏莫臨敵,剛在他力前,時時要留意,調息坎離交,窈窈溟溟趣,雙單可分明,伸縮腰著力,

目光如流電,若履雲霧霽,虛無得自然,道家說無為,養我浩然氣,鬆緊要自主,動時把得固,柔乘他力後,

蓄力如弓圓,上下中和氣,忽隱又忽現,陰陽見虛實,臂脊須圓抱,精神顧四隅,飄飄乎欲仙,無法不容恕,

有象求無象,遍身皆彈力,策應宜守默,一發未深入,彼忙我靜待,發勁似箭直,守默如卧禪,息息任自然,

虛引敵落空,內外混元氣,前四後佔六,浩浩乎清虛,放之彌六合,不期自然至,見首不見尾,不偏亦不倚,

審機得其勢,攻守任君鬥,悟透陰陽理,動似蟄龍起,避免敵重力,欲收放更急,息念要集神,掌握三與七,

意動似懼虎,氣靜如處子,顯隱無與有,道理極微細,元根築基法,世間無難事,神意要集中,欲緊未著力,

見形尋破綻,處處無乘隙,法術二而一,形似游龍戲,舒筋活血脈,水火得相見,奇正得相生,犯者敵即仆,

凝神尋真諦,欲動似非動,蘊藏皆珠玉,欲學果有誠,推動轉輪器,運使求均衡,絲毫不相讓,呼吸細綿綿,

缺一不能立,縱橫與起伏,榮衛得適宜,精研內外功,動靜隨心欲,五總九節力,妙法有和合,靜中還有意,

說難亦非難,久恒與智慧,一觸力即發,螺旋循環氣,腕肘肩胯膝,升降緩而急,兩手輕輕起,陰陽運行數,

一吸氣便提,心虛腹要實,麤成五字訣,欲學持有恒,離塵空虛寂,息念氣自平,看易本非易,華嶽希夷門,

使敵難迴避,逢敵莫惶張,足踏手脚齊,得法可應變,曲伸無斷續,意動氣相隨,氣氣可歸臍,率然取其勢,

後學莫輕視,升堂可入室,拳拳得服膺,默默守太虛,有志事竟成,力行最為貴,欲鬆似非鬆,開闔收與放,

節節力貫串,有術方為奇,轉移有曲折,關節含蓄力,一提氣便咽,首尾不相離。

(奇正得相生,動靜隨心欲,粗成五字訣,後學莫輕視。)

Conscious intent is fundamentally without method; To have a method, this is emptiness

Emptiness yields the natural, Yet having no method is unforgivable....(134 five-character phrases).