|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Japan pu Japan Theme Qin Ci Qin songs More lyrics Later versions | 聽錄音 my transcription and recording 首頁 |

|

Clear Peaceful Music

Subtitle: 七夕 Qi Xi (7th night [of the 7th lunar month] Standard tuning2 played as 1 2 4 5 6 1 2 |

清平樂

1

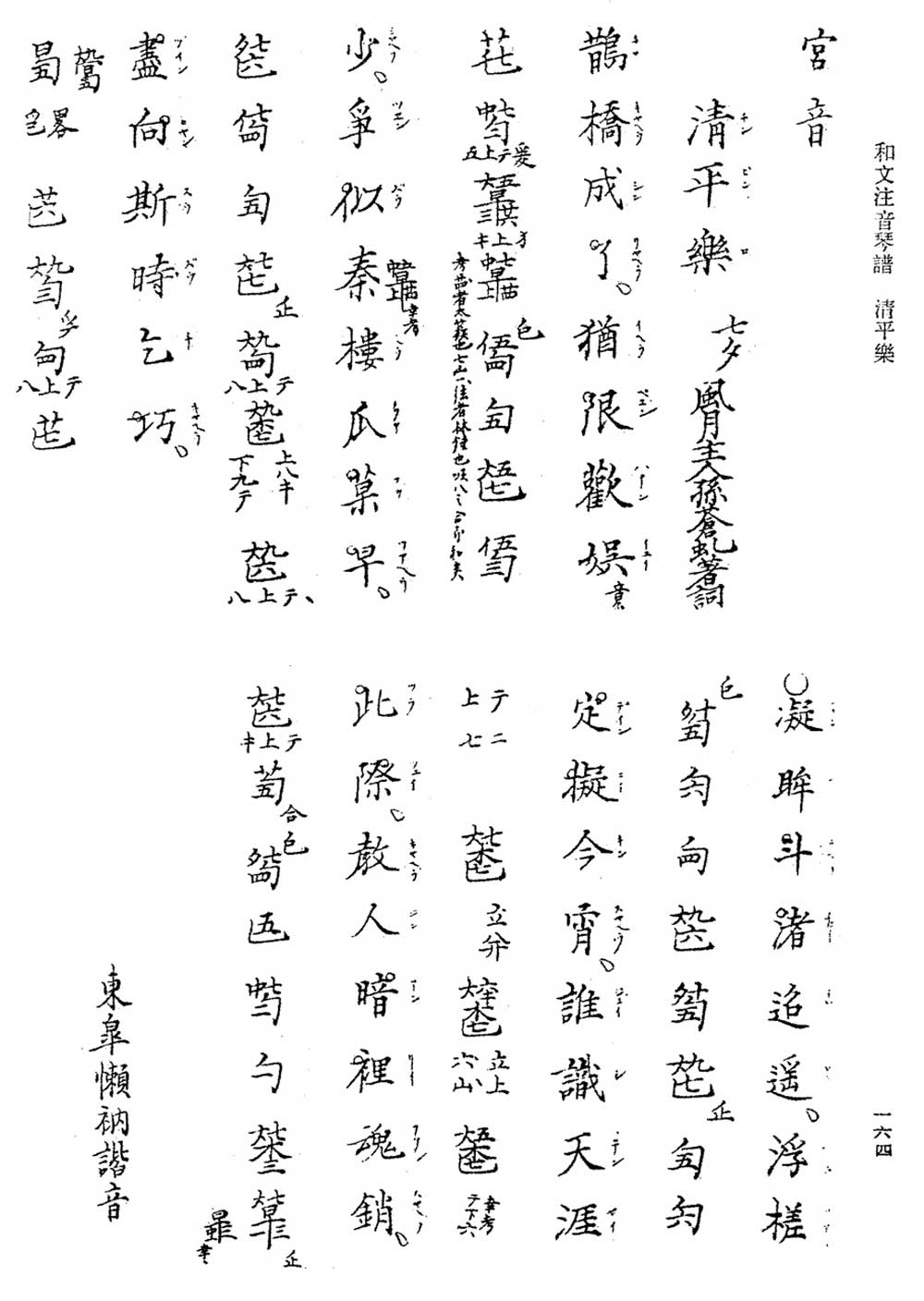

Qingping Yue Hewen Zhuyin Qinpu tablature (1676) 3 |

The title of Qing Ping Yue, the second entry in this handbook, is also the title of a Chinese poetic structure, to be discussed further below. There is very little commentary with this melody (or with any of the later versions of it). Here it was given the subtitle Qi Xi (Seventh Night). This title and the content of the lyrics clearly show that the subtitle refers to the famous legend of the cowherd and weaving girl meeting on the Magpie Bridge (in the Milky Way) once a year on the seventh day of the seventh lunar month. Because of this legend there is a "Double Seventh Festival", also called Beseeching Skills Festival because on this day girls would show off their domestic skills.4 Today this festival is sometimes referred to in English as "Chinese Valentine's Day".5

The present Qing Ping Yue lyrics are given below under Music. A comment before the lyrics attributes them to "Master of the Wind and Moon, Sun Cangqiu".6 Then a statement at the end of the lyrics says: "Toko the Lazy Monk matched the sounds".7 Presumably this means he matched music to the lyrics by Sun Cangqiu, but the origins of the actual melody are not stated.

Qing Ping Yue as a cipai

As stated above, in addition to being a qin song in its own right, Qingping Yue is the name of a cipai: a Chinese poetic structure. Because Qing Ping Yue is the first such melody in this handbook it is given extra attention on this page.

There are said to be over 800 distinct cipai, each with its own structure as determined by the number of characters in all, the lengths of the individual phrases and overall tonal patterns. Each of these cipai is said to have originated in a song with the same structure, but none of the original songs seems to have survived.

Almost certainly such structures were used for qin songs during the Ming dynasty (the focus of this website), but if so it was almost all within the oral tradition. The present handbook, mostly with melodies brought to Japan shortly after the fall of the Ming dynasty, is thus the earliest one with a substantial number of songs in specified cipai.

The standard Qing Ping Yue structure has 46 characters divided into eight lines (phrases), as follows: 4,5;7,6. 6,6;6,6; charts can be found with these details plus the specified tonal structures.

The Zha Guide lists six examples of Qingping Yue in five handbooks. All have lyrics that have this same structure, but these actually comprise four different melodies. None of the versions has a preface or afterword. In fact, amongst these six examples from the qin repertoire only the lyrics of the earliest Japanese version concern the Magpie Bridge story; the other versions, though with lyrics following the same structure, have differing themes as well as melodies.

Likewise, dictionary references to Qingping Yue mention the cipai structure but make no mention of the magpie bridge story. From the present study it seems that most of the lyrics concern love, but not the magpie bridge theme.

On this page are links to transcriptions of three of these four known melodies (the fourth was not printed clearly enough to be deciphered).8 In addition examples are given of further poems in this cipai in the hopes of encouraging readers to try to sing them. There are, in fact, quite a few poems that use this structure.

To sum up the data below regarding the treatment of Qing Ping Yue within the context of traditions regarding cipai, two factors stand out:

The cipai tradition required skills at creating new lyrics following a strict pattern; to the extent that qin players were musicians, perhaps it is natural that they would have created new melodies following such patterns. But then wouldn't they have been happy to suggest that other lyrics could be applied to their musical creations?

Meanwhile the only melody I have been able to find that seems specifically to have been intended for use with a variety of differing lyrics is the one from

1573 or 1585 called

Shi Yin.

00.38

End: 01.14

Translations here are tentative.11 Note also:

1.

清平樂 Qingping Yue (XII/168)

In the Chinese original, although poems in a particular poetic pattern may be named simply by the pattern name, they can also be given a special title. This title may have to do with the topic of the poem, or it may be something like a dedication. In other cases it could simply be the first phrase. Often, it seems, the original survived without a separate title.

As for references, 18003.58 清平樂 says it is the name of a 詞牌

cipai, “一名清平令、億蘿月、醉東風 also called Qing Ping Ling. Yi Luo Yue and Zui Dong Feng", a having 46 字 characters structured in a 雙調 "dual stanza". It gives some history and says there were Tang dynasty poems of this title but with different structures. It then has

詞譜 Ci Pu saying that, "歐陽炯稱李白有應制清平月四首在越調" according to Ouyang Jiong (896-971),

Li Bai wrote on imperial order a set of four Qingping Yue poems in Yue mode. Finally, it adds mention of some other sources, in particular 張輯 Zhang Ji (Song dynasty) and 張翥 Zhang Zhu (Yuan dynasty). The entry quotes no examples.

Further regarding Li Bai's "four poems in Yue mode", if he did write "four Qing Ping Yue" one seems to be lost, unless Ouyang Jun was confusing Li Bai's Qing Ping Yue with his 清平調(清平調詞)三首 three Qing Ping Diao (Ci)", which are in fact 詩 shi style poems each with the structure (7+7)x2, as follows (there are various translations on the internet):

As for the Qing Ping Yue having been written "應制 on imperial order", it has been said that the emperor at that time,

Ming Huang, ordered the lyrics to be written for or about his beloved Yang Guifei.

Following on this, it would seem that a setting of the second Li Bai poem below could be used as an appropriate prelude to the instrumental melody

Wandering in a Lunar Palace first surviving from

1425. Although the original 1425 preface does not mention a specific story, its title is the same as that of an old opera concerning that story, in particular regarding the Rainbow Garment Melody. See further comment on this here but also note that, as seen in the above section titles, other handbooks connected the melody to a different story.

Other lyrics for Qing Ping Yue

It should be noted here that ci poets did not always adhere to the ping and ze requirements of that form. However, it may be of interest to note that the breakdown of individual phrases of poems can be quite strict. For example, in poems where each line has 7+7 characters the 7 character phrases are most commonly sub-divided into 4+3. Here with these ci lyrics, although the overall pattern is given simply as as 4,5;7,6. 6,6;6,6., the actual pattern following both the music and the meaning of the words most naturally almost always seems to subdivide as (2+2),(2+3);(4+3),(3+3). (2+2+2),(3+3).(2+2+2),(2+4). Perhaps the main exception is the poem by Zhao Changqing, which is the example given in

sou-yun.cn for and alternate form of Qing Ping Yue, dividing the second half of the second line into 3+3 instead of 6. Is it significant, then, that all the other examples here seem more naturally to divide that 6 into 2+2+2?

So here now are some well-known examples of Qing Ping Yue, given in chronological order beginning with the three attributed to

Li Bai (ca 705 - 762). All should be singable with the Qing Ping Yue melody linked above.

女伴莫話孤眠, 六宮羅綺三千。

Nǚ bàn mò huà gū mián, liù gōng luó qǐ sān qiān.

In the forbidden chambers on a quiet evening,

With feminine companionship do not speak of lonely slumber,

日晚卻理殘妝, 御前閒舞霓裳。

Rì wǎn què lǐ cán zhuāng, yù qián xián wǔ ní shang.

In the forbidden courtyard on a spring day,

As dusk falls she straightens her remaining makeup,

In the painted hall as morning rising arises,

A glorious luminosity draws out smoke from the hearth,

羅帶悔結同心, 獨憑朱欄思深。

Luó dài huǐ jié tóng xīn, dú píng zhū lán sī shēn.

Wild flowers and fragrant grass,

Regretting a knot tied in shared love,

雁來音信無憑, 路遙歸夢難成。

Yàn lái yīn xìn wú píng, lù yáo guī mèng nán chéng.

Since we parted, spring half over;

Wild geese arrive but bring no letters.

Translation by Burton Watson in The Columbia Book of Chinese Poetry: From Early Times to the Thirteenth Century

今年海角天涯, 蕭蕭兩鬢生華。

Jīn nián hǎi jiǎo tiān yá, xiāo xiāo liǎng bìn shēng huá.

Year after year in the snow I used to get drunk

This year at the end of the earth,

Translation by Wang Jiaosheng as copied from

here (p.77).

Geese come and swallows go,

The cold dew on the window and the clear wind,

極天關塞雲中, 人隨落雁西風。 Jí tiān guān sài yún zhōng, rén suí luò yàn xī fēng.

Limpid qin-like sounds penetrate the night,

Far off in the vast sky along these border regions are clouds,

The title shows that the author himself produced the "limpid" sounds; only a

"soulmate" could appreciate what he was expressing. "Autumn winds" are the common meaning of the original "western winds". And "red collars and green sleeves", here translated as "lady entertainers", could also describe certain birds (27839.xxx).

會昌城外高峰, 顛連直接東溟。 Huì chāng chéng wài gāo fēng, diān lián zhí jiē dōng míng.

Soon dawn will break in the east.

Straight from the walls of Huichang lofty peaks,

This translation, by "袁水拍 等 Yuan Shuipai and others", was copied from Asiabookroom.com. It has been set to modern orchestral music under the title

"六盘山 Liupan Mountain" (easily found online).

2.

Mode: 宮音 Gong Yin?

3.

Image: Original tablature

4.

Double Seventh Festival

5.

Chinese Valentines' Day

6.

蒼虬 Master of Wind and the Moon Sun Cangqiu

"Cangqiu" is most likely a nickname. 32425.61 "cangqiu" says it is a "蒼色虬龍 small horned dragon blue/grey in color", but it can also poetically suggest a gnarled tree trunk or a man with a wispy/curly beard. As a nickname it can be found elsewhere, but I have not yet found anyone surnamed 孫 Sun with this nickname. 44734.30xxx (風月); 7135.xxx (孫); 32425.61xxx (蒼虬). There was actually a poet named 孫覿 Sun Di (1081—1169 CE) who wrote a poem mentioning 蒼虬 cangqiu but as yet I have found nothing to connect him to the present lyrics.

7.

Toko the Lazy Monk Matched the Sounds

8.

Tracing Qingping Yue

Coolness emerges from the oppressive heat (暑! 蕭署 would be "our depressing office"),

Turns of phrase can stir thoughts of home,

1682 subtitles the lyrics "雙壽", adding "檇李朱 雯復齋填詞" (1687 has 朱雯 復齋); with the music (角音 and also 雙壽) 1682 says, "燕山程 雄頴庵諧譜" (1687 has 程雄 頴庵, but its music is different again [宮音]).

The true essence of sound: who truly perceives it?

In a secluded cabin alone we absorb music beyond sound,

With these lyrics 1687 says, "張潮 山來"; with the music (宮音 清平樂), "程雄 隱菴"

Because Qingping Yue is a

cipai this means, as the examples in footnote 1 show, that for one melody many different sets of lyrics can be used. However, those examples are my own doing, and as the examples in the present footnote suggest, this rarely happened in the past. Instead, when the lyrics changed so did the melody, and even when the lyrics stayed the same the melody would often change.

This, however, does not mean that applying new lyrics to old melodies is something that never happened: there was probably a lot within the oral tradition of the qin that was never written down.

9.

Preface

10.

Music (from 和文注音琴譜 (1676; XII/168)

The setting is repeated in 東皋琴譜 1709 (XII/271). The two versions are virtually identical, but 1709 has one character different, changing "菒 gǎo" to "菓 guǒ in the third phrase. It also omits two marginal comments from 1676, as follows:

My interpretation of this is that what looks like "上" should be "卜 over 一" , i.e., an upward slide ("綽 chuo") by the middle finger on the first string (plucking the open fourth string at the same time); the 七 above the 早 is then a mistake: it should be 五 (5th hui), the 早 then forming the note of the fourth string ("taicou") together with an octave above that. "太蔟 taicou" and 林鐘 linzhong are originally note names but can also be used as stud names or perhaps even string names, etc. (e.g. see here).

The modality of this piece is rather problematic, as mentioned

above.

11.

Translation of 清平樂 Qingping Yue (七夕 Qi Xi)

The effort here is to translate the lyrics in a literal way that will help a singer understand each word while singing.

Original preface

None9

Music10

(with 看五線譜 transcription; timing follows 聽錄音 my recording)

*

清平樂(七夕)

Qingping Yue (Qi Xi)

Clear Peaceful Music (Seventh Night)

One section; a mostly syllabic setting by "Lazy Monk Toko" of lyrics attributed to "Master of Wind and Moon

Sun Cangqiu"

00.11

鵲橋成了,猶限歡娛少。 (Perhaps "限" is a mistake for "恨 hen")

Què qiáo chéng liao, yóu xiàn huān yú shǎo

Magpie Bridge has formed, but (heaven) limits this joyous event to (once a year).

爭似秦樓瓜菓早,盡向斯時乞巧。 ("菓 guǒ": 1709; 1676 has "菒 gǎo")

Zhēng sì qín lóu guā guǒ zǎo, jǐn xiàng sī shí Qǐ qiǎo.

It seems as if in the ladies' quarters gourd-fruit (offerings were prepared) early, ready by the time of the festivities.

凝眸斗渚迢遙,浮槎定擬今宵。 (斗渚 13804.xxx)

Níng móu dòu zhǔ tiáo yáo, fú chá dìng nǐ jīn xiāo.

As we stare at the top of the Milky Way so far away, (they seem to be) floating on immortal's rafts as they arrange to meet this evening.

誰識天涯此際,教人暗裏魂銷。

Shuí shí tiān yá cǐ jì, jiào rén àn lǐ hún xiāo.

Who could know that a world so vast, can still reveal hidden passions that consume our very souls!

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

This ci pattern (ci pai) can also be called Qing Ping Le: the character "樂" pronounced "yue" means "music", but it can also be pronounced "le", in which case it can mean "happiness". This helps account for the variety of translations here. These include:

Clear and Even Music

Pure Serene Music

Peaceful Brightness

A Song of Pure Water

Serenade of Peaceful Joy (for a

Chinese movie)

其二:一枝紅艷露凝香,雲雨巫山枉斷腸。借問漢宮誰得似?可憐飛燕倚新妝。

其三:名花傾國兩相歡,長得君王帶笑看。解釋春風無限恨,沈香亭北倚闌乾。

Qing Ping Yue seems to have been quite a popular form, with almost all having the same 46 character structure as with the present lyrics (4,5;7,6. 6,6;6,6.). Chinese online sources such as

sou-yun.cn mention three forms with this 46 character (22+24) structure. It gives an example of each: the first and third are the first and third below by Li Bai; the second, by 趙長卿 Zhao Changqing, is #7 below. The three differ according to their 平仄韻 pingze structure, but it should be possible to sing any of them together with this melody.

玉帳鴛鴦噴蘭麝, 時落銀燈香灺。

Yù zhàng yuān yāng pēn lán shè, shí luò yín dēng xiāng xiè.

一笑皆生百媚, 宸遊教在誰邊。

Yī xiào jiē shēng bǎi mèi, chén yóu jiào zài shéi.

The moon peers through golden window gaps.

Under the jade canopy are mandarin ducks and the fragrance of musk,

While from silver lamps fragrant wax drips down.

In the palace rooms hang silk garments by the thousands.

Just one smile can generate a hundred charming responses,

But while roaming at imperial outings at whose side will he be the guide?

百草巧求花下鬥, 只賭珠璣滿鬥。

Bǎi cǎo qiǎo qiú huā xià dòu, zhǐ dǔ zhū jī mǎn dòu.

誰道腰肢窈窕? 折旋笑得君王。

Shuí dào yāo zhī yǎo tiǎo, zhé xuán xiào dé jūnwáng?

The oriole's feathers seem freshly embroidered.

All the grasses artfully beg as from beneath the flowers they struggle upwards,

But only those wagering their pearl-like beauty fulfil their quest.

Then for the emperor she idly dances in her rainbow(-feathers) garment.

Who could know a waist can move so lithely?

But it is her nimble smile that captivates her lord.

高捲簾櫳看佳瑞, 皓色遠迷庭砌。

Gāo juǎn lián lóng kàn jiā ruì, hào sè yuǎn mí tíng qì.

盛氣光引爐煙, 素影寒生玉佩。

Shèng qì guāng yǐn lú yān, sù yǐng hán shēng yù pèi.

應是天仙狂醉, 亂把白雲揉碎。

Yīng shì tiān xiān kuáng zuì, luàn bǎ bái yún róu suì.

Comes a report that snowflakes are falling.

Rolling high the curtain covers all seems auspicious,

The dazzling light conceals the courtyard paths.

The chill of its pristine reflections bringing out (the sound of the) jade pendants.

It is as though heavenly immortals are wildly drunk,

And have randomly taken the white clouds and crumbled them into bits.

柳吐金絲鶯語早, 惆悵香閨暗老!

Liǔ tǔ jīn sī yīng yǔ zǎo, chóu chàng xiāng guī àn lǎo!

夢覺半床斜月, 小窗風觸鳴琴。

Mèng jué bàn chuáng xié yuè, xiǎo chuāng fēng chù míng qín.

a lonely mountain pass road.

Willows shed golden silk as orioles sing early,

sadly my fragrant bower dims as I age.

alone I lean on a red railing deep in thought.

As I wake from a dream to a half bed moonlit,

from a small window a breeze brushes the qin strings.

砌下落梅如雪亂, 拂了一身還滿。

Qì xià luò méi rú xuě luàn, fú le yī shēn hái mǎn.

離恨恰如春草, 更行更遠還生。

Lí hèn qià rú chūn cǎo, gèng xíng gèng yuǎn hái shēng.

everywhere I look, grief overwhelms me.

Below the steps, fallen plum petals like tumbles of snow -

I brush them off only to be covered with them again.

The road's so long, even in dreams it's hard to go home.

This pain of separation is like the spring grass -

the farther away I journey, the ranker it grows.

挼盡梅花無好意, 贏得滿衣清淚。

Ruó jǐn méi huā wú hǎo yì, yíng dé mǎn yī qīng lèi.

看取晚來風勢, 故應難看梅花。

Kàn qǔ wǎn lái fēng shì, gù yīng nán kàn méi huā.

While picking plum blossoms to put in my hair.

Now twisting all the fallen petals to no good purpose,

I only drench my clothes with pure tears.

My hair at the temples is streaked with grey.

Now that the evening wind is growing in force,

I shall be hard put to it to enjoy plum blossoms.

Zhao was a member of the Song dynasty imperial family living in 南豐 Nanfeng. The 全宋詞 Complete Song Lyrics includes

this comment on the structure.)

冉冉流年嗟暗度, 這心事,還無據。

Rǎn rǎn liú nián jiē àn dù, zhè xīn shì, hái wú jù.

寒窗露冷風清, 旅魂幽夢頻驚。

Hán chuāng lù lěng fēng qīng, lǚ hún yōu mèng pín jīng.

何日利名俱賽。 為予笑下愁城。

Hé rì lì míng jù sài. Wèi yǔ xiào xià chóu chéng.

and once again it is the twilight of autumn.

The fleeting years pass by silently,

and this heart's thoughts, still without anchor.

The soul of a traveler is startled by frequent dreams.

When will fame and fortune become insignificant?

For then I shall laugh and escape the city of sorrow.

Nalan Xingde (1655-1685;

Wiki), a Manchu aristocrat and noted poet, is said to have written this on a wall while on a mission to the northern frontier.

如夢前朝何處也, 一曲邊愁難寫。 Rú mèng qián cháo hé chù yě, yī qū biān chóu nán xiě.

喚取紅襟翠袖, 莫教淚灑英雄。 Huàn qǔ hóng jīn cuì xiù, mò jiāo lèi sǎ yīng xióng.

but who amongst us could be my

soulmate?

Past eras are like a dream,

and a song of frontier misery is hard to inscribe.

and soldiers who resemble wild geese disappearing in the autumn winds.

When calling for lady entertainers,

Do not let them bring tears to heroes.

踏遍青山人未老, 風景這邊獨好。 Tà biàn qīng shān rén wèi lǎo, fēng jǐng zhè biān dú hǎo.

戰士指看南粵, 更加鬱鬱蔥蔥。 Zhàn shì zhǐ kàn nán yuè, gèng jiā yù yù cōng cōng.

Do not say "You start too early";

Crossing these blue hills adds nothing to one's years,

The landscape here is beyond compare.

Range after range, extend to the eastern seas.

Our soldiers point southward to Kwangtung

Looming lusher and greener in the distance.

(Return)

The handbook calls the mode Gong Yin, which should treat the standard tuning as 5 6 1 2 3 5 6 (see 1425). This makes the apparent relative scale 5 6 7 1 2, but allows the melody to end on 1 over 5, hence "gong mode". However, until these final two notes it seems more natural to treat the tuning as 1 2 4 5 6 1 2, which makes the scale 1 2 3 5 6 and allows the eight phrases to end on 5, 1. 5, 1. 6, 2, 6, 4/1. In both cases the final two notes clearly change the tonal center. The reasons for this are not clear, but this something that can also be found in some other old qin melodies as well.

(Return)

Copied from QQJC XII/168.

(Return)

Wikipedia relates the story of the cowherd and weaving girl (牛郎織女 niúláng zhīnǚ) meeting on the Magpie Bridge (鵲橋 quèqiáo) once a year on the Double Seventh. It also gives reasons for the festival also being called "Beseeching Skills Festival" (乞巧節 Qǐqiǎojié).

(Return)

The same is sometimes also said of 元宵節 Yuanxiao Jie (Wikipedia: Lantern Festival; see also under Liangxiao Yin).

(Return)

The attribution here says, "風月主人孫蒼虬著詞 Lyrics by the Master of Wind and the Moon Sun Cangqiu", with no further details about who or when this was.

(Return)

東皋懶衲諧音. "Toko" refers to the Chinese monk Jiang Xingchou. Most likely he created the melody himself, but he may have brought it from China.

(Return)

This listing of extant scores with versions of Qing Ping Yue is largely based on Zha Guide 34/--/501. Page 501 has the three known sets of paired lyrics, all 4,5;7,6. 6,6;6,6 as here. There are transcriptions of all but one: #5 was not printed clearly enough in Qinqu Jicheng and I have not as yet seen any copies more clearly printed.

The lyrics here (given above), attributed to Sun Cangqiu, concern the story of the cowherd and the weaving girl. A comment at the end of the lyrics says: "東皋懶衲諧音 Toko the Lazy Monk Matched the Sounds" (presumably meaning he matched music to the lyrics by Sun Cangqiu).

Basically identical to 1676.

1682 version; lyrics were to the right

This is actually 抒懷操, the second of

four related handbooks. It has different music from the previous and new lyrics but in same pattern. The lyrics

praise

Chen Xiong, mentioning his qin play. This version is repeated in 1738 (with corrections; see below) and 1802 (also below). The lyrics are also repeated in 1687 (XII/400) but with different music. These lyrics are as follows:

凉生蕭署,尙有蟬吟樹。

Liáng shēng xiāo shǔ, shàng yǒu chán yín shù.

攜到氷絲間綽注,碧水丹山凝竚。 Xié dào bīng sī jiān chuò zhù, bì shuǐ dān shān níng zhù.

迴文應動歸心,雙棲伴爾彈琴。 Huí wén yīng dòng guī xīn, shuāng qī bàn ěr tán qín.

宛似鹿門小隱,不須世覓知音。 Wǎn sì lù mén xiǎo yǐn, bù xū shì mì zhī yīn.

Yet the cicadas still hum through the trees.

With hands on the icy smooth silk strings sliding up and down,

The emerald waters and vermillion mountains curdle in place.

As companions together we play qin.

It seems we can just go to Deer Gate for a bit of seclusion,

No need for the outside world when seeking close companionship.

1687 #5 (version A)

This third musical setting of Qing Ping Yue is actually the first of two in

Song Sheng Cao. The other, #26

(see ), has the same lyrics as 1682 but new music. The tablature itself, with no other copies than this one in 1687, seems to have a few errors; I have tried to correct them in my transcription. The extra stroke (挑六) at the end of line 1 allows the tablature to follow the traditional

pairing method of one character for each right hand stroke. The last noe (C over G) contrasts sharply with the previous passages where the tonal center seems to be A, but this is actually quite common in the early qin repertoire.

文音誰識,止解傳鈎剔。

Wén yīn shuí shì, zhǐ jiě chuán gōu tī.

試問宮商分呂律,若個真能入室。 Shì wèn gōng shāng fēn lǚ lǜ, ruò gè zhēn néng rù shì.

隱庵獨契希聲,新詞盡付韶音。 Yǐn ān dú qì xī shēng, xīn cí jǐn fù sháo yīn.

何日溪邊洗耳,烹茶許我閒聽。 Hé rì xī biān xǐ ěr, pēng chá xǔ wǒ xián tīng.

Most only know how to pluck and hit.

We are asked how individual notes can produce melodies,

How can we become truly knowledgeable?

New lyrics are all entrusted to the sacred music of antiquity.

When will we go the stream and wash (society's dirt) from our ears?

Then brew tea so that I can be at leisure as I listen.

1687 #26 (version B)

This fifth version is the second Qing Ping Yue in 1687 (#26). It has the same lyrics as in 1682 (see above) but new music. Unfortunately, because the copy from Qinqu Jicheng, as shown at right, not only seems to have a number of mistakes but also was not printed clearly enough, I have not yet felt confident about making a transcription.

Same lyrics and 角音 music as 1682, but it has no separate comment about the music, saying only, "朱復齋先生填詞".

Same as 1738.

(Return)

Many melodies in the Japanese handbooks have attributions of music and/or lyrics, but few have further commentary. Here the only comments are the attributions to Sun for the lyrics and Toko for matching the melody.

(Return)

(This sung version is only a guideline, it needs a better rendering)

This setting follows the standard pairing method of one character for each right hand pluck except in the second half of the third line, where the characters "定 ding" and "宵 xiao" seem to have been paired to slides, not plucks. Note, however, that here there also seems to be a mistake in the tablature's use of "撞"(written "立") followed by "分開"(written "八over开"). Usually these are written in reverse order, and I have never seen an explanation that shows clearly how it was intended to be played.

(Return)

Some terms are still not clear to me (e.g. 斗渚 douzhu; 13804.65 斗宿 dousu is the Big Dipper; 渚 zhu means islet or sandbar).

(Return)

Return to the top or to the

Guqin ToC