|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Teaching HIP Caoman Yin Singing Xian-Weng Chart tracing Xianweng Cao & Caoman Yin Books |

|

|

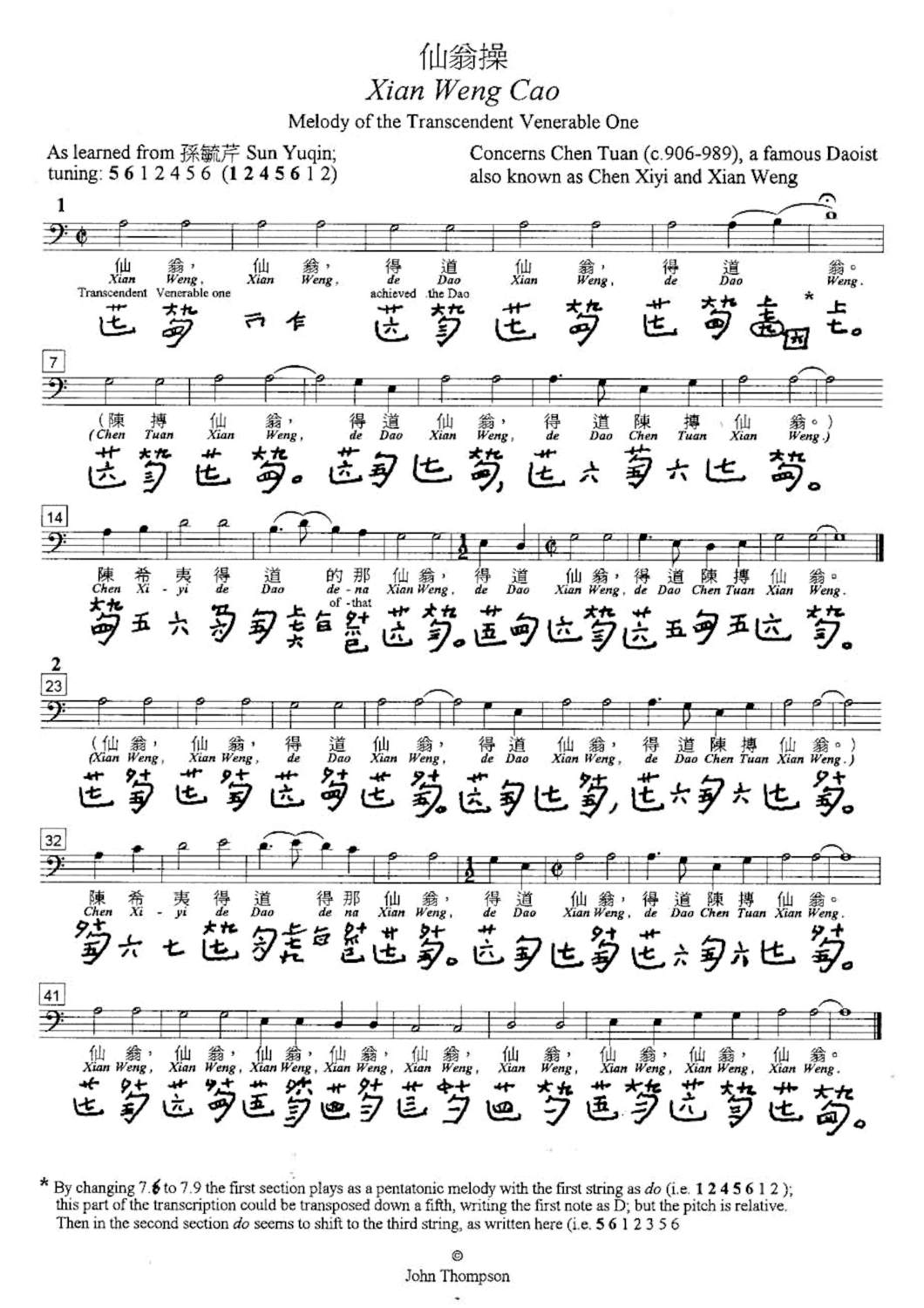

Melody of the Transcendent Venerable One

Standard tuning (no mode indicated): 2 5 6 1 2 3 5 6 and/or 1 2 4 5 6 1 2 |

仙翁操 1

Xianweng Cao (or Xian Weng Cao) |

|

- Compare Caoman Yin, now retroactively often called Xianweng Cao

- Contrast earlier beginner's melody Tiaoxian Pin (1525)/Yi Sa Jin (1539) |

To begin guqin (pdf) 3 |

This piece, the title of which might also be translated as Melody of the Ancient Immortal, is the the first melody I learned when in 1974 I began studying qin in Taiwan with Sun Yü-Ch'in. We jumped right into the piece and he said little of its origin. Later I heard from Tong Kin-Woon that this Xianweng Cao may have originated as a Meian School melody, though details of this are not clear and it is not in Meian Qinpu.4

Still later I learned that in China most beginners, if they played a melody called Xian Weng Cao, it was related to or similar to the melodies previously called Cao Man Yin, Tiaoxian Runong and the like (see tracing chart). It is not clear what brought about either the new version or the change in titles for the old one.

Although originally learned simply as a beginner's melody, this Xianweng Cao can variously be considered as a beginner's exercise, a warm-up piece, and a vehicle for transporting a player into an appropriate mood for qin play. But could it be so relaxing as to induce sleep? If so, could that explain the melody's connection with Chen Tuan, a famous Song dynasty recluse credited with having devised sleep meditation?

Another question concerns the nickname "Xianweng" (or Xian Weng: Transcendent Immortal), applied here to Chen Tuan.5 "Xianweng" does not seem elsewhere to be associated with Chen Tuan, but here as "xian-weng" it seems to have a special role. As explained here, the character "xian" in this context can refer to a plucked open string and the one for "weng" to refer to a stopped string playing the same relative pitch. This xian-weng combination, called xian-weng yin appears throughout Xianweng Cao: if you look at the transcription you can see that every time these lyrics appear together it follows this structure. In the first section the xian-weng are always an open and a stopped string played with two strings in between, while in the second section there is always one string separating them, until the second half of the last line, where it reverts to two strings separating them. This simultaneously is a lesson on the relationship between the seventh, ninth and tenth hui (harmonic marker) on a qin.

Meanwhile, as the lyrics remind us, Chen Tuan is said to have "de Dao", attained the Way; and another name for him in the song text, "Xiyi", reminds us that this title was apparently bestowed on Chen Tuan in 984: "Xiyi Xiansheng, Master of the Invisible and Inaudible".6 There has never been a suggestion that Chen Tuan himself played qin; nevertheless, he is often connected with a series of related melodies that, generally under the title Caoman Yin, were also clearly designed for beginners. As described further on its page, these melodies all feature some of the most basic techniques in guqin play. Where they have lyrics these usually repeat the various names of Chen Tuan (including Xianweng, with the same double meaning as above), adding that he attained the Way.

Some old handbooks suggest that unless one begins with simple melodies, one will never master the qin. My own teacher told me that the seemingly most simple pieces were the ones that required the greatest art.7 Xianweng Cao, one to two minutes long, begins and ends on the same two notes. This naturally allows one to play the melody over and over. Such repetition can be settling, not to mention meditative;8 and it also encourages the player to focus on the subtle tones that can be produced by a silk string qin when played well: one should learn the essence of qin play from the very beginning.

When I began studying with Sun Yü-ch'in in 1974, as he began by teaching me Xianweng Cao he said nothing about its origins (about which see further). He also did not sing the lyrics, but I remember seeing them at that time. He did give me some tablature, but always said students should copy him, not look at tablature. The tablature of Xianweng Cao I had in Taiwan had number notation underneath but no lyrics. For my own transcription into staff notation I followed this version quite closely, adding the lyrics from memory, then later checking it with the version in Yinyinshi Qinpu.

Musically the first section of Xianweng Cao often has the same note repeated first on an open string then on a string stopped in the ninth position. The second section begins with notes played on open strings followed by the same notes played on strings stopped in the 10th position (or position 10.8 in the case of the third string); it ends with a recap of all these positions. Repeating the notes in stopped and open positions serves both to attune the ear to playing in tune and to make the player familiar with fundamental note relationships. This is also what is described above as the xian-weng sound.

In my own version there is one significant note I change from the written version I found in Taiwan: on the 11th note I slide the thumb from the ninth position up to position 7.9 instead of to the written 7.6. As a result, in the first section of the melody becomes purely pentatonic (do re mi sol la) with the first string considered as do; the first note, an open seventh string, is re. In the second section the melody remains purely pentatonic if the third string is now considered as do; the first note is still the open seventh string, but now it is considered to be la.9

Playing and viewing the melody this way gives a sense of how tonal centers can shift, particularly in the qin melodies as found in Ming and earlier tablature. For more on this, search this site for "qin tunings".

Although there is no indication of when Chen Tuan actually became connected to a qin melody such as this, it seems to have taken at least a few centuries: although the earliest known publication of such a melody, originally called Caoman Yin (Strum Silk Prelude),10 had no lyrics and made no mention of Chen Tuan, the second surviving publication, in 1557, again had no lyrics but mentions him in the prelude.11 The third, then, from 1573 where it is called Tiaoxian Runong, mentions him in both the prelude and the lyrics. Regarding the title, the words "cao man" already suggest that this is an essential beginner's melody. It is important to note, however, that although there is a clear melodic relationship between these old versions of this melody and the ones played today either as "Caoman Yin" or as "Xianweng Cao", the version of Xianweng Cao I learned in 1974 has similar lyrics to the old Caoman Yin in spite of its quite different melody. This Xianweng Cao, once again, is transcribed above and recordings are linked below.

Versions of Caoman Yin, discussed in more detail on its own page, can be found in many early qin handbooks, under various titles.12 They are almost always included with the essays at the beginning of the handbooks, rather than with the regular melodies. Perhaps this indicates they were considered only as introductory exercises (or as meditations). The earliest (1552) and some later ones are written in longhand tablature.13

None of the old handbooks seems to have had a melody specifically called Xianweng Cao. As for those mentioning Xianweng in the title, the earliest I have found is Tiao Xian-weng Ge in Qinxue Lianyao (1739), but it seems less of a melody and more of instructions for describing in terms of xian and weng two notes of the same pitch but on different strings (thereby emphasizing the different colors you can get from playing the same pitch on different strings, a characteristic of all the Xianweng melodies).14 After this there are several more with this title, plus others such as Tiao Xianweng Zhinan or Hexian Xianweng Diao. All have more in common with Caoman Yin than with what I learned as Xianweng Cao. Although the one from 1739 might seem to be in transition to the modern version, as far as I have been able to hear this transition never really continued. As for modern publications, Yinyinshi Qinpu (Hong Kong, 2000) has two entries called Xianweng Cao;15 fhe first version is quite similar to the one I learned from my teacher, Sun Yü-ch'in, but it is missing two sections; the second one from 2000 contains some phrases from earlier versions. Yinyinshi Qinpu has no commentary on either of these melodies, and so it is still difficult to know how the modern version came about.

| Melody and lyrics 17 (Listen with transcription; watch video; video for students) | A transcription (pdf) 3 |

Compare Caoman Yin, now retroactively often called Xianweng Cao.

Compare Caoman Yin, now retroactively often called Xianweng Cao.

Two sections, untitled.

陳摶 Chen Tuan (Proper name of Chen Tuan)

陳希夷 Chen Xiyi (Nickname of Chen Tuan)

得道 de Dao (Achieved the Dao)

的那 dena ("of that", filler syllables with no meaning)

- 仙翁,仙翁,得道仙翁,

Xianweng, Xianweng, de Dao Xianweng,[得道翁,陳摶仙翁。

[De Dao weng, Chen Tuan Xianweng.得道仙翁,得道陳摶仙翁。]

De Dao Xianweng, de Dao Chen Tuan Xianweng].陳希夷得道的那仙翁 ,

Chen Xiyi de Dao dena Xianweng,

(Chen Xiyi attained the Dao of the Transcendent Immortal.)得道仙翁,得道陳摶仙翁。

De Dao Xianweng, de Dao Chen Tuan Xianweng]. - [仙翁,仙翁,得道仙翁,得道陳摶仙翁。]

[Xianweng, Xianweng, de Dao Xianweng, de Dao Chen Tuan Xianweng.]陳希夷得道的那仙翁 ,

Chen Xiyi de Dao dena Xianweng,得道仙翁,得道陳摶仙翁。

de Dao Xianweng, de Dao Chen Tuan Xianweng.仙翁,仙翁,仙翁,仙翁 ,

Xianweng, Xianweng, Xianweng, Xianweng,仙翁,仙翁,仙翁,仙翁。仙翁。

Xianweng, Xianweng, Xianweng, Xianweng, Xianweng. Xianweng.

The straight brackets [] indicate the part not included in Yinyinshi Qinpu

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

1.

Transcendent Venerable One (仙翁 Xianweng; also: Immortal Elder, Ancient Immortal, etc.)

This is not a nickname specific to Chen Tuan; for a long time it had already been applied in particular to Daoist recluses, though references to this term said to date back to the Han dynasty are somewhat suspect; likewise with 葛洪神仙傳 Ge Hong's

Biographies of Immortals with its stories of xianweng living in the mountains and transmitting secret arts. Here is a set of standard references:

For dictionary references, 仙翁: 391.xxx and no connection to Chen Tuan at 1/1146 (same with 42618.1013 陳摶 Chen Tuan: there is no mention of xianweng). What 1/1146 actually has is the following:

①稱男性神仙,仙人。

- 唐崔曙《九日登望仙台呈劉明府》詩:「關門令尹誰能識?河上仙翁去不回。」

- 宋何薳《春渚紀聞•鄭魁銘研詩》:「仙翁種玉芝,耕得紫玻璃。」

- (林逋)«西湖佳話•葛嶺仙跡》:「神異如此,人人皆道他是仙翁再世。」

- 陰屠隆《綵毫記•仙翁指教》:「仙翁拜揖,念小生與仙翁素乏平生,何以見顧?」

(Immortal elder)

1. A term for a male shenxian (immortal, transcendent); an immortal.

- Tang, Cui Shu (?-739; Daoist poet), (his poem) "On the (Double) Ninth Day, Ascending to the Terrace for Gazing at Immortals, Presented to Prefect Liu"

(in some editions it is one of the "300 Poems of the Tang Dynasty"; see

translation with calligraphy).

The complete poem is:

漢文皇帝有高台,此日登臨曙色開。 The third line can be translated, "The governor at the mountain pass, who even knows him? The Immortal Elder by the River" ("of the River?") has gone off never to return.” Unfortunately, no sources identify this xianweng. "Going never to return" (去不回) is reminiscent of these lyrics about Wangzi Qiao, but he is more associated with mountains than with rivers. The significance of this riverside immortal thus remains a mystery.

三晉雲山皆北向,二陵風雨自東來。

關門令尹誰能識,河上仙翁去不回。

且欲近尋彭澤宰,陶然共醉菊花杯。 - Song, He Wei (1077–1145). Chunzhu Jiwen: Zheng Kuiming's Inkstone, includes the phrase, “An immortal elder (仙翁) planted jade mushrooms, then cultivated it as purple crystal.”

- (Lin Bu; 967-1028): Beautiful Tales of West Lake: Immortal Traces of the Ge Ling (Mountain Range near Hangzhou): “So wondrous was he: everyone said he was an Immortal Elder (仙翁) reborn!” (This is a very strange line; it is the third line, 4+10, in a poem that is otherwise (4+4)x7.

- Recluse Tulong (1543-1605), Record of Colored Brushes, Guidance of Immortals: “The Immortal Elder bowed in greeting, saying: ‘This humble student and the Immortal Elder (仙翁) have had no prior acquaintance in life - why should I be shown such regard?’”

As for translating "xianweng", "Immortal Elder" is a more literal translation but for the purposes of this qin melody "Transcendent Venerable One" seems more meaningful. Breaking it down, 翁 Weng by itself is a generally affectionate term that can be translated simply as "oldster". As for "仙 xian" (or "仙人 xianren"), it is commonly translated as "immortal" but, as in English, this does not necessarily signify a belief that the person literally lives on as a biological entity. It may suggest simply that the person's spirit lives on, perhaps leaving open the issue of whether this spirit has power (suggesting a sort of divinity), has consciousness, or simply has a powerful reputation. If the person is still alive (or even being considered historically), referring to him or her as a "xianweng" may simply suggest that the person has transcended such issues as life and death: after all, who are we ordinary mortals to know or question such possibilities?

On the other hand, in ancient China there was also a definite interest in the idea of and possibilities for real immortality here on earth. Some sense of this can be found through Wikipedia, beginning with the article Xian (Taoism).

In addition, Joseph Needham wrote about the connection between alchemy and the search for immortality in Science and Civilization in China. For example, in Chapter 33. Alchemy and Chemistry (Part III of Volume 5, Chemistry and Chemical Technology) he describes various substances that have sometimes been said to have been used to create a sense of immortality, such as amanita muscaria (fly-agaric? a phantasmagoric mushroom; see below); and substances used to attain physical immortality via, for example, some metallic substances such as gold, iron and mercury), some of this perhaps somehow related to the fact that ancient diets were often iron-poor in northern areas where there were no fresh green vegetables in winter.

(Return)

2.

Tuning and mode

Mode is generally not indicated with this piece. As for tuning the strings, the pitch is relative, with 1=do, 2=re, etc.. In my transcription do is written as c, but the exact pitch depends on such things as the size and quality of the instrument and strings.

As explained here and at the bottom of the transcription, I changed one finger position from the way I learned it: 7.6 to 7.9 in measure 5. In this way the first section is completely pentatonic 1 2 3 5 6 if the tuning is considered 1 2 4 5 6 1 2 . The second section remains completely pentatonic 1 2 3 5 6 if the tuning is considered 5 6 1 2 3 5 6.

This sort of changed tonal center, perhaps more like transposition, can also be found in at least one other melody,

Tiao Xian Pin aka

Yi Sa Jin.

(Return)

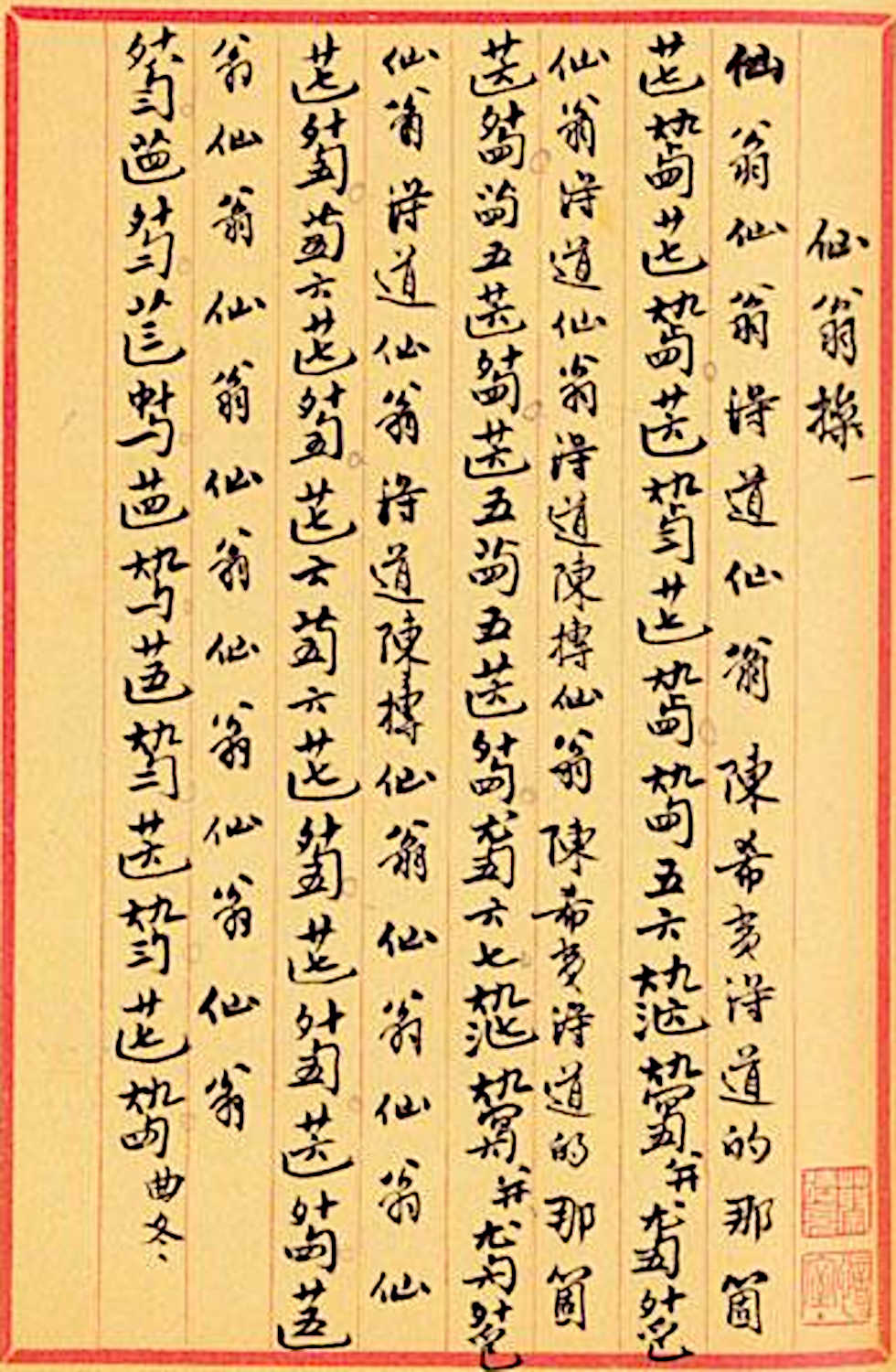

| 3. To begin guqin: tablature for Xianweng Cao (pdf; transcription above) |

王海燕傳授 transmitted through Wang Haiyan

This copy comes from 怡蘭琴譜 Yi Lan Qin Pu, compiled by 陳欽怡 Chen Xinyi and published in 2009 by the 怡蘭琴齋 Yilan Qinzhai.

Wu Zonghan (1902—1991) was at student of Meian Qin School master Xu Lisun. In 1950 he left China and went to Hong Kong, where he taught qin until 1967, when he moved to Taiwan. Here 王海燕 Wang Haiyan (1945- ) was one of his students, but then in 1972, for health reasons, he moved to Los Angeles. This suggests that she copied his tablature for Xianweng Cao in Taiwan a few years before I studied there. It quite likely was this tablature that I used when I learned the melody from Sun Yuqin. However, in my copy the tablature was paired with number notation.

There is further detail about the origin of this melody in the next footnote.

(Return)

4.

Origin of this version of Xianweng Cao (see previous footnote)

According to Dr. Tong Kin-Woon, before he began studying with Sun Yuqin in Taiwan he learned this Xianweng Cao in 1969 from the Meian School master 吳宗漢 Wu Zonghan (1902—1991), originally a student of 徐立蓀 Xu Lisun (徐卓 Xu Zhuo). At the time Wu was teaching qin at the National Academy of Arts (then called 國立臺灣藝術專科學校 Guoli Taiwan Yishu Zhuanke Xuexiao) in 板橋區 Banqiao district, just south of Taipei. Dr. Tong says at the time Sun Yü-Ch'in was not teaching qin and few people knew he played. After Tong met Sun he introduced Sun to Wu and they became friends. Thus, when Wu left for Los Angeles in 1972 Sun took over the teaching position in Banqiao. Tong then began studying with Sun, but Tong believes that at this time he must have introduced Wu's Xianweng Cao to Sun, to use as a beginners' melody. Tong does not know about the history of the piece before this, and only more recently played a version of the Caoman Yin that many people today are calling Xianweng Cao.

(Return)

5.

仙翁 Xian Weng as a nickname for Chen Tuan 陳摶 (867 - 989!)

Some biographical details for Chen Tuan are given in a footnote under Caoman Yin. The nickname xianweng is discussed further above.

(Return)

6.

Master of the Inaudible and Invisible 希夷先生 (Xiyi Xiansheng)

9025.26 希夷 xiyi: 無聲曰希,無色曰夷,為道之本體也。 Xi (希) is what cannot be heard; yi (夷) is what cannot be seen. The name thus refers to the basic structure of the Dao. It also suggests longevity, hence 希夷﹕靈芝也 a longevity plant, perhaps a phantasmagoric mushroom.

(Return)

7.

"Simple" melodies as the most difficult

Mr. Sun actually said this in connection with the melody

Xiang Fei Yuan, played today very much as it is written in Taigu Yiyin (1511). Taigu Yiyin has many simple songs. At that time there was apparently debate about singing style vs. purely instrumental style, but I haven't found specific details about this. One can imagine that the debate involved the relative value of a simple style vs. a complex one, but again I have not found the details.

(Return)

8.

Centering through repetition

Although Xianweng Cao is the first melody I learned I still enjoy playing it, and in doing so often repeat it a number of times using the last two notes of one repetition as the first two notes of the next, sometimes singing, sometimes not. The recordings linked here (especially with the transcription) should give an idea. This playing of a simple melody (or even a simple note pattern) repeatedly in order to settle down or center oneself before playing more complex pieces might be considered as an aid to meditation: do it until the mind is empty while playing. This is in some ways comparable to the old custom of Chinese calligraphers rubbing their own ink. To do this they add water to the inkstone, then rub with another stone. To get in the right mood they might at times spend a considerably longer time than necessary doing this before beginning to write. (Compare the "jade bracelet structure" [玉環體 yu huan ti] mentioned for Guanshan Yue).

(Return)

9.

Different modality in each section

This is not changed by the fact that in the transcription the first note of each section is written as "A": changing the relative tuning within one piece from 1 2 4 5 6 1 2 to 1 2 3 5 6 would be very confusing. There is further comment under

mode, including mention of other examples of this.

My understanding of mode is discussed in some detail here (note in particular this section) and elsewhere on this site.

(Return)

10.

操縵引 Caoman Yin. See the separate introduction to

Caoman Yin, which can also be translated as Adjust the Strings Prelude

(Return)

11. In Xingzhuang Taiyin Buyi, attributed to 蕭鸞 Xiao Luan, who called himself 杏莊老人 the Old Man of Apricot Village. The preface in this 1557 version is even more specific in its suggestion that one must begin with such a melody.

(Return)

12.

Cao Man and other alternate titles

Zha Fuxi's index 39/--/552 操縵 Cao Man mentions only the version in the Japanese Toko Kinpu, giving 仙翁操 Xianweng Cao as an alternate name. I assume the fact that they are not included in the melody sections is the reason that he did not properly index them. I have so far found 27 versions up to 1930, but because they are not in Zha's index I quite likely have missed some.

(Return)

13.

Longhand tablature (文字譜 Wenzi pu)

The earliest example of this tablature is Jieshidiao You Lan. As for Xianweng Cao, there are at least six examples of it written out in longhand (see in this tracing chart).

The modern shorthand tablature developed out of long hand tablature, apparently during the Tang dynasty. Although this fact may suggest great antiquity for Xianweng Cao, it could also simply have been done in modern imitation of that style. (For another use see also here.)

(Return)

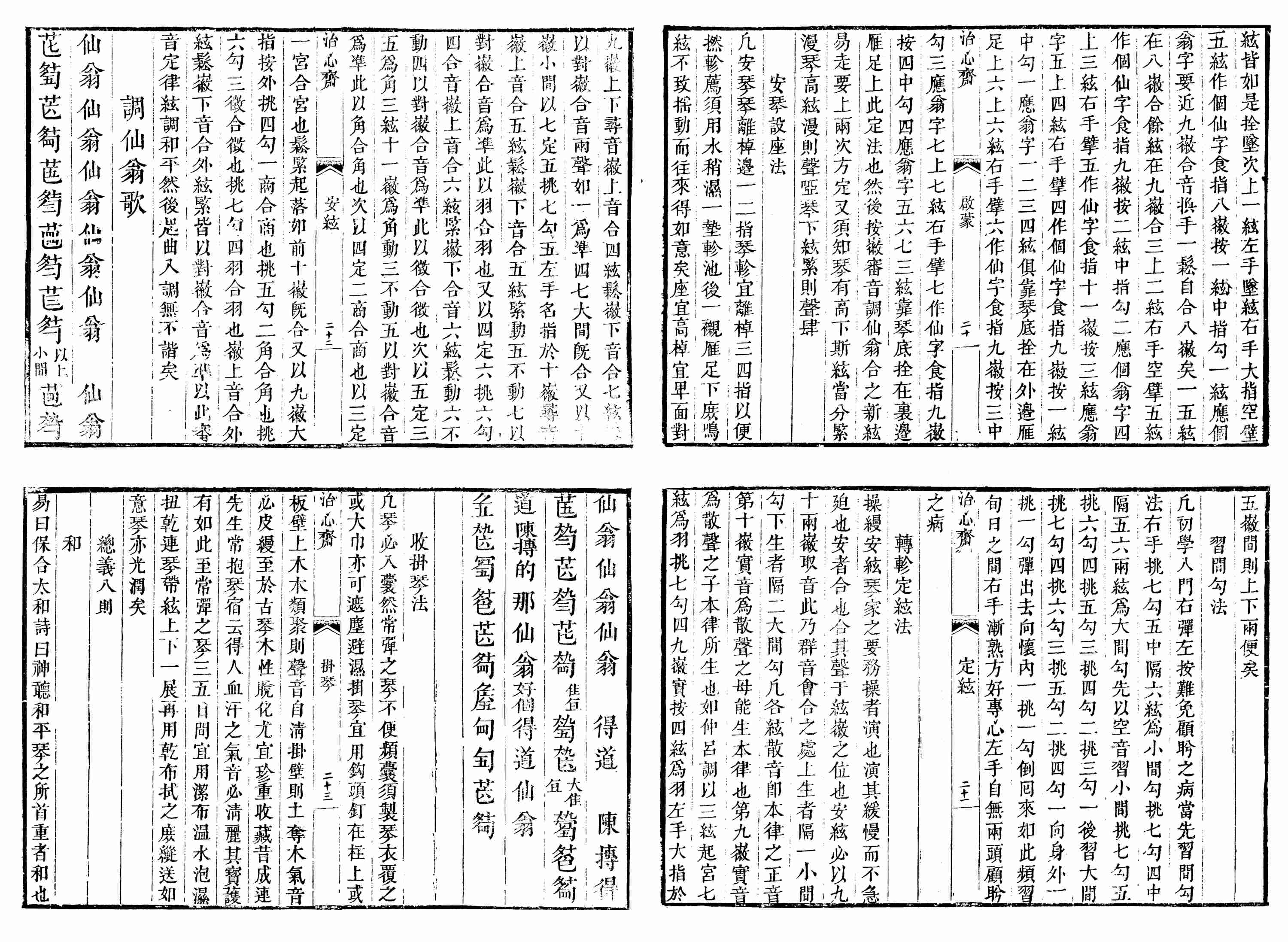

| 14. 調仙翁歌: Tuning by Singing Xian-weng (from 琴學練要 Qinxue Lianyao, 1739; XVIII/85) | When beginning to play qin, from 1739 |

Also also in a Beijing facsimile, Folio I, p.23. As can be seen on the left side of the image at right (expand), the version from 1739, called 調仙翁歌 Tiao Xian-weng Ge (Tuning by singing Xian and Weng), begins like the end of the version I learned from Sun Yuqin, but it then has some phrases from the earlier versions. Before and after it are a group of related essays called 啟蒙歌 Qi Meng Ge, meaning something like "lyrics for beginning to play". Much of it concerns xian (transcendent) and weng (elder citizen: immortal), with xian referring here to the sound of an open string, weng referring to the same pitch played on a stopped string, and xian-weng meaning to play xian and weng together (consecutively). The specific essays on the pages shown at right are as follows (the first was continued from the previous page):

Also also in a Beijing facsimile, Folio I, p.23. As can be seen on the left side of the image at right (expand), the version from 1739, called 調仙翁歌 Tiao Xian-weng Ge (Tuning by singing Xian and Weng), begins like the end of the version I learned from Sun Yuqin, but it then has some phrases from the earlier versions. Before and after it are a group of related essays called 啟蒙歌 Qi Meng Ge, meaning something like "lyrics for beginning to play". Much of it concerns xian (transcendent) and weng (elder citizen: immortal), with xian referring here to the sound of an open string, weng referring to the same pitch played on a stopped string, and xian-weng meaning to play xian and weng together (consecutively). The specific essays on the pages shown at right are as follows (the first was continued from the previous page):

- 上絃次序法: Initial tuning (use xian weng starting with open 5th string and first string in 8th position.

- 安琴設座法: Setting the qin on a table: where and how.

- 習間勾法: Practising "interval plucking" (xian-weng method until this can be done without moving head)

- 轉軫定絃法: Turning pegs to fix tuning: match 7 and 4, then 7 and 5, 6 and 4, etc.

- 調仙翁歌: Tuning by singing xian-weng (like mm.41-48 of this transcription, then compare 1585 ending)

- 收掛琴法: Storing and hanging a qin (in a bag, on a wall, clean it: sleep with it?)

Qinxue Lianyao does not seem actually to have a complete Xianweng melody. It has a lot more technical analysis of modes but Zha Fuxi's commentary suggests it is very confusing and contradictory.

(Return)

| 15. 愔愔室琴譜 Yinyinshi Qinpu (Hong Kong, 2000) | First melody in the handbook |

Yinyinshi Qinpu is the handbook of Hong Kong qin teacher 蔡德允 Tsar Teh-yun (Cai Deyun). The first version there is quite like the one I learned; it has lyrics but to my knowledge no one sings them.

Yinyinshi Qinpu is the handbook of Hong Kong qin teacher 蔡德允 Tsar Teh-yun (Cai Deyun). The first version there is quite like the one I learned; it has lyrics but to my knowledge no one sings them.

The second version in this handbook does not have lyrics but it has some phrases from the earlier Cao Man Yin.

(Return)

16.

But see the preface to the 1557 version with Caoman Yin.

(Return)

17.

Original lyrics

The original Chinese lyrics, as in the above

transcription, are by themselves as follows,

- 仙翁,仙翁,得道仙翁,

[得道翁,陳摶仙翁。

得道仙翁,得道陳摶仙翁。]

陳希夷得道的那仙翁 ,

得道仙翁,得道陳摶仙翁。 - [仙翁,仙翁,得道仙翁,得道陳摶仙翁。]

陳希夷得道的那仙翁 ,

得道仙翁,得道陳摶仙翁。

仙翁 ,仙翁 ,仙翁 ,仙翁 ,仙翁 ,

仙翁 ,仙翁 ,仙翁 ,仙翁。

(Return)

Return to the Guqin ToC or to play qin.