|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Taiyin Daquanji ToC Folio 5-6 ToC / "Folio 6": ToC Parts: 1&2 / 3-8 / 9-20 / 21-24 / R-L hands / Preludes / Closing / Wusilan fingerings | 網站目錄 |

| Taiyin Daquanji 1 | 太音大全集 |

| Folio "6", Closing 2 | 卷六:I/103a |

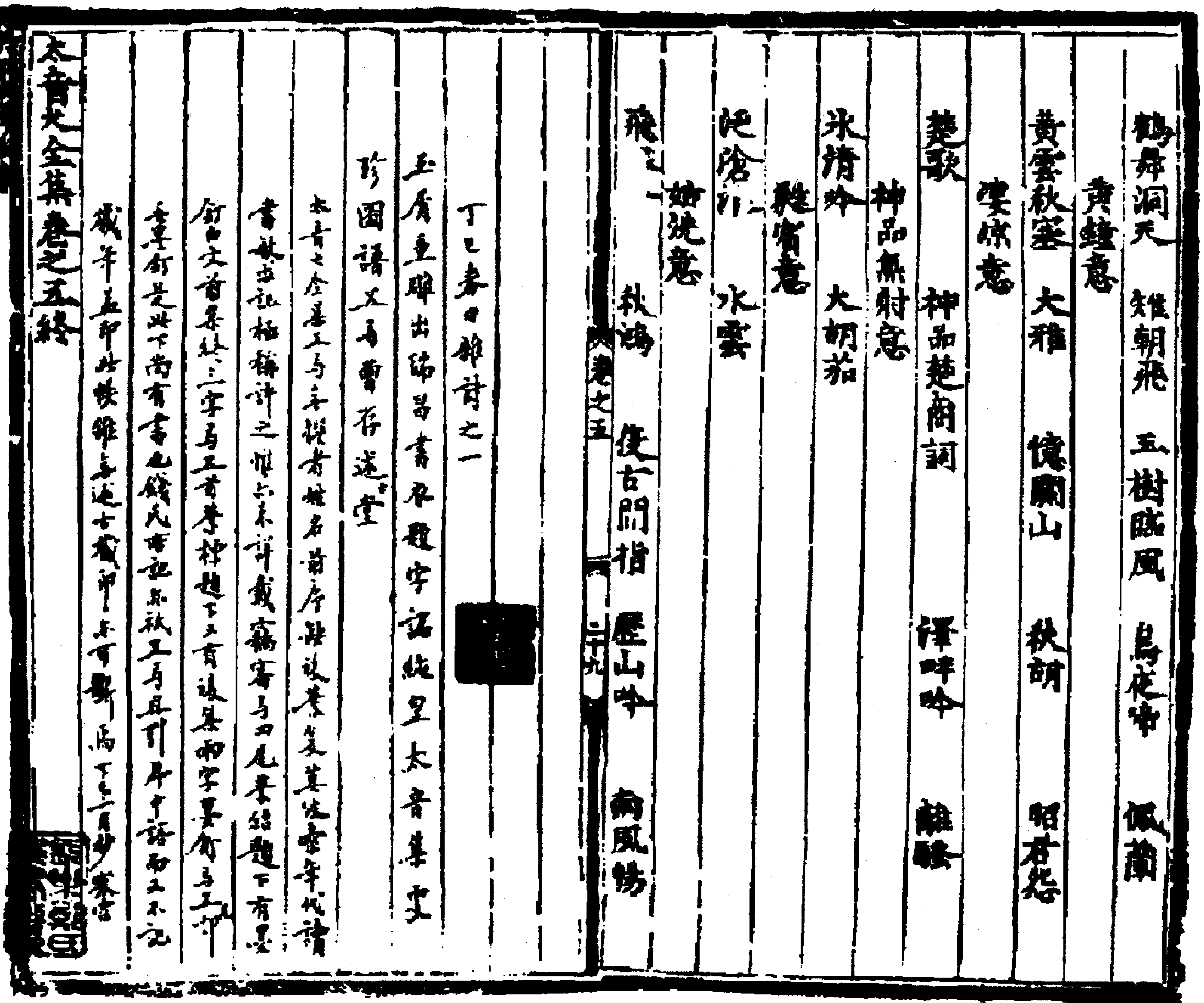

The right half of the image at right continues on from the melody list that started on the previous page. On the left hand is what seems to be a new poem and modern (20th c.) commentary by the then-owner of the book)

The right half of the image at right continues on from the melody list that started on the previous page. On the left hand is what seems to be a new poem and modern (20th c.) commentary by the then-owner of the book)

-

丁巳春日雜詩之一 First entry in a Miscellaneous Poem Collection, Spring of a dingsi year (1917).

- 瑞昌 Ruichang is near 九江 Jiujiang in Jiangxi province; its significance here is unclear.

- 㢧 9914. quotes 真話 saying 㢧:與卷同 it is the same as juan ("folio")

- For the Hall of Narrating Antiquity (Shugutang) see 述古堂書目 its catalogue. It was a book collection belonging to Qian Zeng 錢曾 (1629-1701; www.chinaknowledge.de).玉屑重雕出瑞昌,書衣題字認純皇。

太音集便珍圖譜,五㢧曾存述古堂。Jade shards (small treasures?) finely styled have emerged from Ruichang,

The book cover is inscribed with characters in what must be imperial yellow.

The Great Sounds Collection cherishes treasured tablatures,

Its five folios were once preserved in the Hall of Narrating Antiquity.The commentary continues with the following text. In the print version this is almost illegible but Tong Kin-Woon copied it out (see in TKWQF endnote 287 p.21 top), beginning near the middle of the page (Dr. Tong's own commentary begins at the end of that page). As can be seen, the original modern commentary begins by giving the date as "丁巳" (ding si: here 1917), stating the title, then saying that the name and date (whether it is the name of the compiler or the date of compilation) cannot be determined because there was no original preface or afterword.

太音大全集五㢧。無選者姓名。前序缺後葉。复莫改索年代。 「讀書敏求記」極稱許之惟亦未詳載。竊審㢧四尾葉結題下有墨釘白文「前集終」三字,㢧五首葉標題下又有「後集」兩字墨釘,㢧五尾却無墨釘,是此下尚有書也。錢氏所記亦祇五㢧,且引序中語而又不記歲年,盖卽此帙。雖無述古藏印,亦可斷焉。丁巳二月杪寒雲。】」 Dr. Tong then adds his own commentary beginning,

唐按,述古堂卽清初錢曾之書齋,錢氏曾藏此書,見其「讀書敏求記」....

Tong adds: Shugutang was the book collection of the early Qing dynast (bibliophile) Qian Ceng. The Ceng family's storing of this volume is mentioned in the ""Dushu Minqiuji (Record of Reading Books by an Inquiring Mind)....This is now continuing at 21 bottom, adding quite a lot of furter details about various editions of Taiyin Daquanji.

- The last line on the page above says, "太音大全集卷之五終。 End of Taiyin Daquanji Folio 5".

I/103b

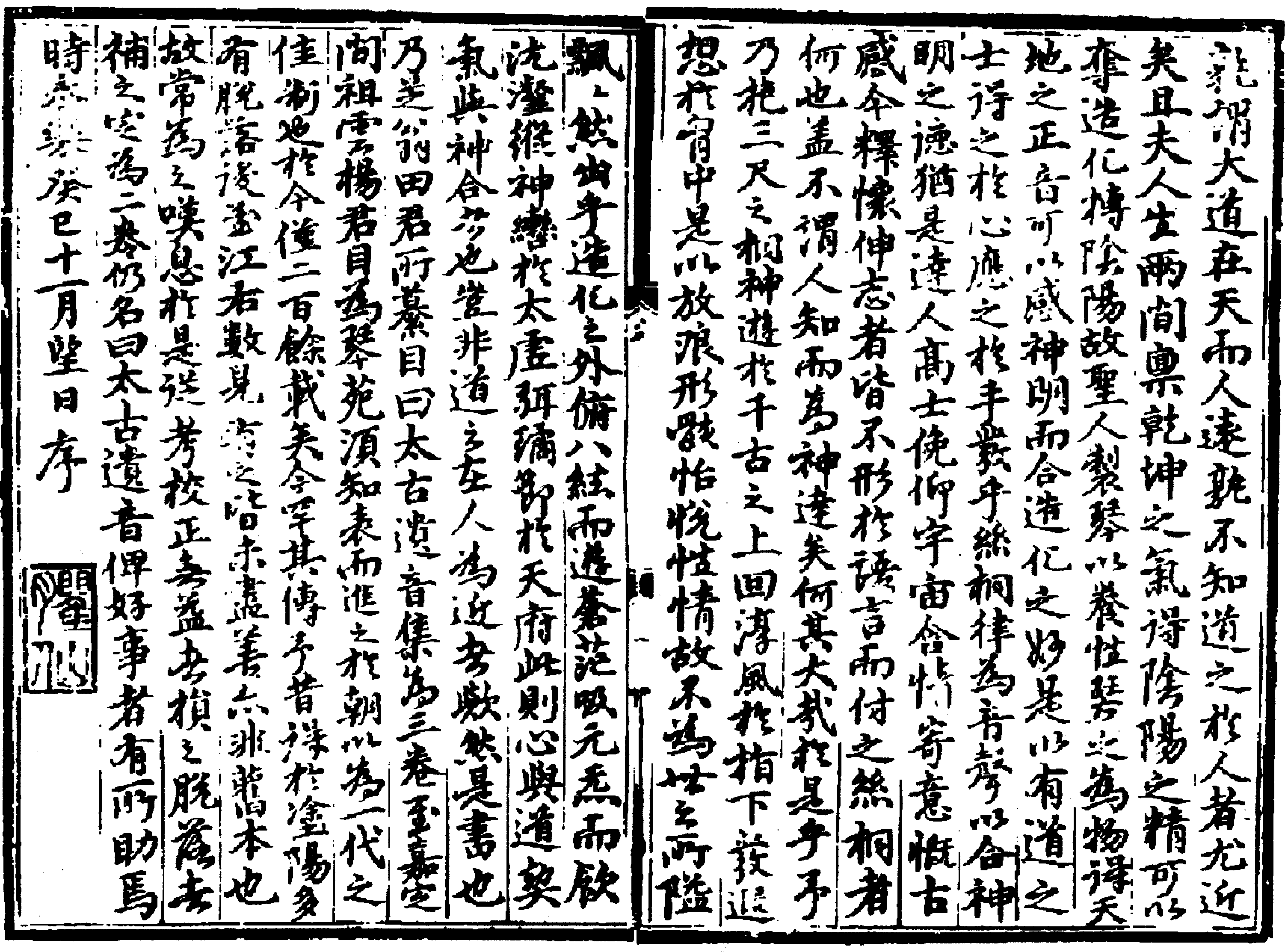

序 Preface (used as a final afterword; I/103b)

Considered to have been written by Zhu Quan himself. The original text is:3孰謂大道在天而人遠?孰不知道之於人者尤近矣?且夫人生兩間,稟乾坤之氣, 得陰陽之精,可以奪造化、摶陰陽。故聖人制琴以養性。琴之為物,得天地之正者,可以感神明而合造化之妙。是以有道之士,得之於心,應之於手,發乎絲桐,律為音聲,以合神明之德。

猶是達人高士,俛仰宇宙,含情寄意,慨古感今,釋懷伸志者,皆不形於語言, 而付之絲桐者,何也?蓋不謂人知,而高神達矣,何其大哉!

於是乎,乃抱三尺之桐,神遊於千古之上,回淳風於指下,發遐想於胸中。 是以放浪形骸,怡悅性情,故不為世之所隘。飄飄然出於造化之外,俯八絃而游蒼茫,吸元氣而飲沆瀣,縱神轡於太虛, 弭蹫節於天府。此則心與道契,氣與神合者也。豈非道之在人為近者歟?

然是書也,乃袁均哲君所纂,目曰《太古遺音》,集為三卷。 至嘉定間,祖雲楊君目為《琴苑須知》,表而進之於朝,以為一代之佳制也。於今僅二百餘載矣,今罕得其傳。予昔得於塗陽,多有脫落,後至江右,數見有之,皆未盡善,亦非舊本也,故常為之嘆息。於是從考校正,無益者損之,脫落者補之,定為二卷,仍名曰《太古遺音》,俾好事者有所助焉。

時永樂癸巳十一月望日序。臞仙。

Who says the Great Dao resides in the heavens, far from humans? Who is it that does not know that the Dao is especially close to humanity? Actually, humans live between the two, endowed with the qi (life force) of qian-kun (heaven and earth: the cosmos), while attaining the jing (more tangible essence) of yin-yang (forces applied to earthly life), and thus able to seize creation and wield yin and yang. Thus, the sages created the qin for cultivating this basic nature. The qin, as an object, has the correct alignment with heaven and earth, and it can be used to move the spirits and align with the mysteries of creation. And so it is that those with the Dao in their hearts, respond to it with their hands, and express this through silk strings and tong wood, transforming it into sound to resonate with the virtues of the spirits.

Likewise, accomplished individuals and lofty scholars, gaze up and down at the universe, in control of their emotions and trusting their thoughts, lament the past and feel for the present. When releasing their hearts and extending their aspirations, why do they not express this in words but instead entrust it to silk and wood? It is because this is not something that people can know, but rather something that elevates them to the divine and reaches the transcendent.

Thus, embracing a (little more than) three-foot-long qin, their spirits travel across the ages. They bring back the pure winds through their fingertips and release distant thoughts from their chests. By this, they free their physical forms and delight in their true nature, refusing to be confined by the mundane world. Light and carefree, they transcend creation, bending over the eight strings to wander the vastness, inhaling primordial qi and drinking heavenly dew. They unleash their spirit's reins in the great void and harmonize with the rhythms of the heavenly courts. This is where the heart aligns with the Dao, and the qi merges with the spirit. Is this not proof that the Dao is indeed near to humans?

Now, regarding this book: it was (originally) compiled by Master Tian Zhiweng and entitled Taigu Yiyin (Music Bequeathed from Antiquity), originally in three volumes. During the Jiading period (1208-1224) Master Yang Zuyun renamed it Qinyuan Xuzhi (Essentials of the Qin Garden) and presented it to the court, recognizing it as a masterpiece of its time. Now, more than two hundred years later, it is rarely transmitted. I once obtained a copy in Tuyang, though it was incomplete. Later, when I traveled to Jiangyou ("the left side of the river"), I saw several copies, but none was satisfactory, and none were the original version. Thus, I often sighed in regret. Therefore, I have carefully collated and corrected these materials, removing what was useless and supplementing what was missing, reducing it to two volumes while retaining the original name Taigu Yiyin, so that it may be of assistance to enthusiasts.

Written on the day of the full moon in the eleventh month of the Guisi year of the Yongle era (1413), by the Emaciated Immortal (Zhu Quan).

There is then a seal saying "臞仙 Qu Xian", i.e., Zhu Quan. Regarding the reference to two and three 卷 juan ("folio") versions, there is a two juan edition of Taigu Yiyin here; it is missing the second juan but it does have a complete Table of Contents. Based on that it is difficult to consider that Taigu Yiyin as being an early source of the others. And as yet I have not heard elsewhere of a three juan version. As for the reference to an 八 eight instead of 七 seven string qin, it looks like a scribal error.

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

1. Taiyin Daquanji

See comments with right hand technique explanations. The Taigu Yiyin in Qin Fu p. 102 is more clear.

(Return)

2.

Explanations by translator

See comments concerning the structure of the original text.

(Return)

3.

Punctuated version of text copied from

www.douban.com.

(Return)

Return to Taiyin Daquanji ToC