|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| SXGQP ToC / Tracing chart and Note count chart for Qiu Jiang Ye Bo and Yin De / Mid Autumn Moon | 聽錄音 My recording & transcription / 首頁 |

|

09. Autumn River Night Anchorage

- Shang mode, standard tuning: 2 5 6 1 2 3 5 6, but played as 1 2 4 5 6 1 2 |

秋江夜泊

Qiu Jiang Ye Bo 1 Hanshan Bell Resounds 3 |

This title occurs for the first time in Songxianguan Qinpu (1614); it then survives in 27 more handbooks from 1614 to the present.4 It has thus for a long time been quite a popular melody. There have been some noteworthy changes over time, but the modern versions are still remarkably similar to the 1614 "original".

This title occurs for the first time in Songxianguan Qinpu (1614); it then survives in 27 more handbooks from 1614 to the present.4 It has thus for a long time been quite a popular melody. There have been some noteworthy changes over time, but the modern versions are still remarkably similar to the 1614 "original".

Here "original" is written in quotes because, in fact, the entire melody is clearly related to an earlier one called Yin De (Hidden Virtue). Yin De can be found in four handbooks from 1425 to 1585 and once again in 1670. Also, virtually the same as Yin De is the melody Chumu Yin (Shepherd's Chant), found as a prelude to Mu Ge in Taiyin Xupu (1559) and Qinpu Zhengchuan (1561).5

A study of how the melody Hidden Virtue became Autumn River Night Anchorage could thus be edifying on the subject of melody transmission. Musical analysis of the two could also say much about the development of musical styles.6

Complicating the comparisons, according to Zha Fuxi's Index only one of the 27 handbooks with this title has any commentary, Qinxue Rumen (1864). This, combined with the obvious appeal of the melody, has perhaps led different people over time (or at least in modern times) to come up with differing ideas about its meaning and origin.

The commentary in Qinxue Rumen (1864) begins as follows,7

This seems to be saying the beauty of this melody is in its totality, not in each separate part. However, it has no information about the melody's source. And the full text of the commentary goes on only to suggest there may be some confusion about which note is gong (do).8

A recording of the 1864 version is linked below as is a recording of the final version listed by Zha, the version in the 1931 edition of Mei'an Qin Handbook (see in chart). This Mei'an version is basically the same melody (though it has changed the relative tuning), but here it is attributed to Su Dongpo, with the 1959 edition (so too late for the Zha Guide) giving details. In particular, it says Qiu Jiang Ye Bo depicts musically the whole of Su Dongpo's 11th century poem Red Cliff Rhapsody #1, as follows:

- Casting off the boat

- Punting and loud singing (compare the second half of Yin De section one)

- Hoisting sails and approaching mid-stream in the next section

- Further singing, descriptions of the scenery, lowering the sails and re-anchoring in the last section.

Given that before 1931 none of the versions is known to have had any commentary at all on the melody's content, it is not clear what the source is for the details in 1931/1959. Could this be a free-association connection to the fact that Su Dongpo wrote a night anchorage poem: Night Anchorage at Niukou?9

One final story, again apparently uncorroborated, seems to come from around the same time. The earliest mention of it I have found so far is in the paragraph that introduces the transcriptions of two recordings of the melody published in Guqin Quji, Vol. 1 (1962). This commentary suggests that Qiu Jiang Ye Bo was created extemporaneously around 1600 during a visit to the famous Hanshan (Cold Mountain) Temple in Suzhou. It says,10

It was Zhang Ji's poem, included in the collection 300 Tang Poems, that made Maple Bridge famous. The actual words, however, cannot be paired to the present music using the traditional method for pairing lyrics and music with the guqin.12

Riverside maples and the fires of fishermen enter my restless sleep.

Just then beyond the walls of Suzhou, at the Cold Mountain Temple,

The midnight bell rings, and (the sound) reaches my boat.

Other translations include those by Witter Bynner (A Night-Mooring near Maple Bridge) and Cai Zong-Qi (Nightly Mooring at the Maple Bridge)

As for the earliest known versions of this melody, called Yin De, three of the four are virtually identical to each other, and Chumu Yin is almost the same as these. This perhaps indicates it was a melody being passed down through its tablature, rather than by active play. One might then theorize that Yan had played from the earlier tablature, and that his inspiration at the Cold Mountain Temple led him to transform this material enough that he gave it a new name.

Qiu Jiang Ye Bo has four sections, dividing them as in Chumu Yin, which broke Yin De Section 1 into two sections. Each section of Qiu Jiang Ye Bo then begins the same as the corresponding part of Yin De, except that section one of Yin De opens with a dayuan putting the thumb on the 8th position of the fourth string, while Qiu Jiang Ye Bo puts the thumb on the 7th position. The latter part of each section also follows similar contours.

The change of modality between Qiu Jiang Ye Bo and the earlier Yin De is even more notable. Yin De (as well as Chumu Yin) and Qiuqiang Ye Bo are both said to be in the shang mode. As with other shang mode pieces they both have do (1) as the fundamental tone, but in Yin De (and Chumu Yin) mi is sometimes flatted, sometimes not. In the 1614 Qiu Jiang Ye Bo the mi is never flatted, instead in some passages mi flat is changed to fa. In Dahuan'ge Qinpu even more so in later handbooks there is neither mi flat nore fa, leaving only the unchanged mi.14

Although until recently there seem to have been no other recordings of Yin De, there have been numerous recordings of Qiu Jiang Ye Bo, though mostly of later versions (i.e., without the interesting non-pentatonic notes of the earliest version).15 My own is linked below.

Original Preface

None 16

Music (See transcription; timings follow 聽 my recording)

Four sections (compare Yin De)17

(00.00) 1.

(00.38) 2.

(01.05) 3.

(01.46) 4.

(02.26) Harmonics

(02.41) End

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

1.

Autumn River Night Anchorage (秋江夜泊 Qiu Jiang Ye Bo)

25505.69 only 秋江 Qiu Jiang. This seems to mean a river in autumn, not a river name. The title could also be Autumn River Night Mooring (or At Night Mooring on a River in Autumn). A "mooring" suggests being tied to another object at the surface level of the water.搯撮三聲

(Return)

2.

Shang mode (商調 Shang Diao)

See Shenpin Shang Yi as well as further comments above

(Return)

3.

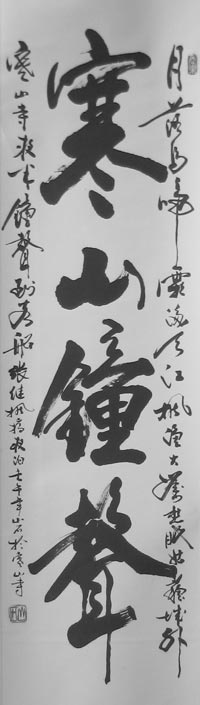

Image: The Hanshan Bell Resounds (寒山鐘聲 Hanshan Zhong Sheng)

Quite a few famous calligraphers have written out these four characters, which are paraphrased from a famous poem by 張繼 Zhang Ji, the original text (below) of which is written to the right and left of the four large characters, followed by "張繼楓橋夜泊 Zhang Ji, Maple Bridge Night Mooring", then 壬午年山石於寒山寺.

(Return)

4.

Tracing Qiu Jiang Ye Bo

The chart below is based on Zha Fuxi's index 30/236/--. Could Qiu Jiang Ye Bo (or something like it) have been the original name, one which Zhu Quan rejected? Some handbooks call the piece 秋江晚波 Qiu Jiang Wanbo, and 徽言秘旨 Huiyan Mizhi (1647) mistakenly calls it 秋江晚釣 Qiu Jiang Wandiao (Autumn River Night Fishing), which is correctly the title of another piece in 8 sections. There are no other recordings of Yin De but several are available of Qiu Jiang Ye Bo.

(Return)

5.

芻牧吟 Chumu Yin (prelude to

Mu Ge)

Details are under Yin De.

(Return)

6.

From Yin De to Qiu Jiang Ye Bo

The connection between Qiu Jiang Ye Bo and Yin De was pointed out to me by Mitchell Clark, perhaps while I was preparing my reconsruction for a 2002 qinconference in Suzhou; I don't recall how he learned about it but at one time he was a student of Wu Wenguang. Studying the connection between the two melodies might begin with listening to the two melodies while looking at the transcriptions of each, as well as the one on a separate page that aligns the beginning of each section side by side. These are:

- The recording and transcription of Yin De (Hidden Virtue)

- The recording and transcription above of Qiu Jiang Ye Bo (Autumn River Night Anchorage)

- This transcription putting next to each other the beginning of each of the four sections.

The introduction above gives various details of the melodies but none shows an awareness of the melodic connection between the two. There is some further discussion of this in various places on this website such as

here.

(Return)

7.

Qinxue Rumen Afterword (XXIV/317

The complete afterword in Qinxue Rumen (1864) is as follows:

桐君識

As for this melody, its notes are ancient and vast, one must follow along in its relaxed pace to get this; each phrase by itself does not suffice to realize this. This melody/mode uses the first string as gong. For melodies that have the first and sixth string as gong then if you treat the third string as gong you do not need to lower the third string, you just avoid playing it as an open string....

Translation incomplete. Here the text seems just to go on and explain the different hui positions you need to play when, instead of the third string, you play the open first string as gong. It is not clear why Zha Fuxi (p.236) only copied the preface' opening sentence and changed the last character from 接 to 織 (as above: could it be related to this content?

(Return)

8.

Which open string should play gong (do)?

There is a theory that in standard tuning do should be played on the open third string. This means that the old shang mode is "wrong" to have the first string as do and so something must be changed. Perhaps this is the reason that, without significantly changing the melody, Meian Qinpu changed the tuning for Qiujiang Yebo from 1245612 to 1235612. (See further comment above about how the modal aspect of the original version of this melody changed over time.)

(Return)

9.

Niukou Night Anchorage (牛口夜泊 Niukou Ye Bo)

20379.5 牛口 just says "牛之口 cow's mouth" (not "cattle crossing") with two literary references but none geographical. However, there are several Niukou on maps, including one on the Yangzi river in Hubei province, quite far upstream from Chibi. It begins,

There is a full text with translation at scholarshipchina.cn. Note that there is also a poem of this title by Su Shi's younger brother 蘇轍 Su Zhe; it begins 行過石壁盡,夜泊牛口渚。

([5+5] x 8).

(Return)

10. Qiu Jiang Ye Bo commentary from Guqin Quji, Vol. 1 (1962), p.8, #19

秋江夜泊

最早見於明代的《松絃館琴譜》(1614)。據說是根據唐代張繼的詩: 「月落烏啼霜滿天。江楓漁火對愁眠。姑蘇城外寒山寺。夜半鐘聲到客船。」所作之曲。於是認為曲中「打圓」的指法是在描寫鐘聲。

Seen earliest in the Ming dynasty Songxianguan Qinpu (1614). It is said that this was inspired by a Tang dynasty poem by Zhang Ji that say, As the moon goes down a raven calls, frost fills the sky. Riverside maples and the fires of fishermen enter my restless sleep. Just then beyond the walls of Suzhou, at the Cold Mountain Temple. The midnight bell rings, and (the sound) reaches my boat. Thus it is thought that the finger technique "hit around" that begins the piece represents the sound of this temple bell.

The commntary does not credit its source. Similar commentary, also without any crediting, came with a 1995 recording by 劉正春 Liu Zhengchun; see The Art of Qin Music, Hugo HRP 7136-2. The Chinese original is,

據傳說嚴天池和琴川社友夜遊寒山寺時據唐張繼(楓橋夜泊)詩即景生情而譜此曲.

According to tradition Yan Tianchi and friends from the Qin River Society went to Hanshan Temple one evening, and was inspired by a poem by Zhang Ji to create (write out?) this melody.

Once again, I have not yet been able to find out where this story comes from. The CD preface also says "the tune and rhythm of the piece is very old, one should appreciate the content slowly, and never hurry at any note." This comes from the commentary in Qinxue Rumen (1864; previous footnote). The only other handbook with commentary is apparently Mei'an Qinpu (see above).

(Return)

11.

"Create" (譜 pu)

See in Glossary: the use of "pu" as a verb is not clearly defined. Besides "create" it could also mean simply to write down something that was already created.

(Return)

12.

Zhang Ji: Maple Bridge Night Anchorage (張繼,楓橋夜泊)

Also: Maple Bridge Night Mooring. The original Chinese for this poem is:

江楓漁火對愁眠。

姑蘇城外寒山寺。

夜半鐘聲到客船。

Sun Daolin recites this poem on the Hugo CD Appreciation of Tang Poetry Quatrains, Vol.I.

(Return)

13.

For another mention of a raven (crow) calling see

Wu Ye Ti.

(Return)

14.

Changes in shang mode characteristics

I discovered these changes in shang mode characteristics, and wrote about them on this website, in 2002 while preparing three "new" Songxianguan Qinpu melodies for a conference held in that in Suzhou in honor of

Yan Cheng, considered the founder of the Yushan School.

The chart under Yin De has further comments on the mode. It is interesting to compare these changes with the what happened in the development of Yu Qiao Wenda around the same time.

(Return)

15.

Early recordings of Qiu Jiang Ye Bo

For example, the Sitong Shenpin collection of historical recordings from the 1950s includes the follow six recordings (three [![]() ] are linked here):

] are linked here):

- 夏蓮居 Xia Lianzhu

; see

bio; source not mentioned; keeps some fas and other non-pentatonic notes

; see

bio; source not mentioned; keeps some fas and other non-pentatonic notes

- 詹澄秋 Zhan Chengqiu from Yuhexuan Qinxue Tiyao

- 黃雪輝 Huang Xuehui

from Qinxue Rumen; seems still to be close to the 1614 version; faster tempo than #1 but also keeps some fas and other non-pentatonic notes.

from Qinxue Rumen; seems still to be close to the 1614 version; faster tempo than #1 but also keeps some fas and other non-pentatonic notes.

- 程午嘉 Cheng Wujia

from Meian Qinpu, transcribed in Guqin Quji 1/192; almost purely pentatonic but still related to 1614 throughout.

from Meian Qinpu, transcribed in Guqin Quji 1/192; almost purely pentatonic but still related to 1614 throughout.

- 張育瑾 Zhang Yujin

from

Tongyinshan Qinpu ("proto-Meian"); mostly pentatonic but still a number of fa and other non-pentatonic notes

from

Tongyinshan Qinpu ("proto-Meian"); mostly pentatonic but still a number of fa and other non-pentatonic notes

- 朱惜辰 Zhu Xichen

from Meian Qinpu. Like #4 almost purely pentatonic but the most rhythmic of these 6 and with distinctive ornamentation.

from Meian Qinpu. Like #4 almost purely pentatonic but the most rhythmic of these 6 and with distinctive ornamentation.

The recorded Qinxue Rumen- and Meian-related versions are discussed further above. Note that the Meian version use of lowered third tuning does not seem to change the modality.

(Return)

16.

Preface

The only preface listed in Zha's Guide is from Qinxue Rumen (1864; see above).

(Return)

17.

Music

The timings here follow my recording.

(Return)

Appendix 1: Note count chart comparing

隱德 Yin De and

秋江夜泊 Qiu Jiang Ye Bo

The notes in my staff notation transcriptions all indicate relative pitch: "C" is actually "do", "D" is "dre" and so forth.

For both melodies the most common notes are C and G (do and sol); also most phrases here end either on do or sol. These are indicators that the mode can be called a do-so mode.

In addition, for Qiu Jiang Ye Bo many phrases center on re before going down to do. Re in Chinese is "shang" and this does seem to be a characteristic of many melodies said to be in shang mode. This also happens towards the end of Yin De but is not quite so obvious.

Yin De at times substitutes a flatted third for mi (the standard whole tones third). In contrast, Qiu Jiang Ye Bo substitutes the fourth (fa) for mi. This seems to be quite a common characteristic of qin melodies at the end of the Ming dynasty. though perhaps it is unique to certain schools.

In Section 3 of Qiu Jiang Ye Bo the Bs occur when the tonal center has changed from C (relative pitch do) to A (la) whereas the flatted Bs occur when the tonal center has moved back to C (do).

Both codas are played in harmonics (Comment).

| \ Rel. Pitch

Section \ |

A | Bb | B | C | C♯ | D | Eb | E | F | F♯ | G | G♯ | other | Total |

| 隱德

Yin De |

||||||||||||||

| 1 | 5 | 18 | 9 | 1 | 12 | 1 | 10 | 56 | ||||||

| 1.a | 6 | 15 | 6 | 1 | 14 | 17 | 1 | 60 | ||||||

| 2 | 15 | 15 | 7 | 6 | 12 | D/G: 1 | 56 | |||||||

| 3 | 13 | 15 | 13 | 6 | 7 | 18 | 72 | |||||||

| 尾聲 Coda | 3 | 1 | 2 | 6 | ||||||||||

| Totals | 39 | 66 | 36 | 8 | 39 | 1 | 59 | 1 | 1 | 250 | ||||

| 秋江夜泊

Qiu Jiang Ye Bo |

||||||||||||||

| 1 | 5 | 21 | 11 | 4 | 10 | 16 | 77 | |||||||

| 2 | 6 | 1 | 19 | 3 | 9 | 1 | 17 | 56 | ||||||

| 3 | 18 | 2 | 3 | 23 | 14 | 15 | 15 | 90 | ||||||

| 4 | 16 | 16 | 15 | 7 | 3 | 20 | 77 | |||||||

| 尾聲 Coda | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | |||||||||

| Totals | 47 | 3 | 3 | 80 | 44 | 35 | 14 | 70 | 306 |

Appendix 2: Chart Tracing Qiu Jiang Ye Bo / Yin De

See under 隱德 Yin De

Return to the annotated handbook list or to the Guqin ToC.