|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Taiyin Daquanji ToC / Previous - Next: Folio 4 | 網站目錄 |

|

Taiyin Daquanji

Folio 3 (complete) : Hand Gesture Illustrations (1/63b-80a) 1 2 |

太音大全集

卷三,丁﹕手勢圖 |

| Colophon on Fingering3 | Folio 3 has two text entries before its illustrations (I/63b) |

The ancients, in accordance with musical sounds, wrote them down in tablature. They considered the hand positions as if they were physical objects, indicating a profound significance. This (significance) is difficult to understand. And sometimes they are traditionally written down incorrectly, and even more, difficult to distinguish. Now I am familiar with a lot of educated (people) and have received their writings and verbal explanations. Although I have not received all of the possible knowledge in this regard, it approximates pretty well the feelings of the person and the principles of the matter (of these techniques), and I can teach this to people just beginning to study this. I wouldn't dare to try to set myself up as a teacher of this to people who already understand music.

Distinguishing the Fingers

4

Cai Yong said,

the food finger is the head finger (index finger);

the leading finger (dictionary: thumb) is the middle finger;

the name finger is the no-name finger (ring finger).

Zhao Weize said (in his Explanation of Cai Yong's finger techniques),

Zhao Yeli reformed this, saying,

The finger of heaven is what the right thumb resembles;

The finger of earth is what the right index finger resembles;

The sun finger is what the right middle finger resembles;

The moon finger is what the right ring finger resembles.

A great wind is what the left thumb resembles;

A light cloud is what the left index finger resembles;

A high mountain is what the left middle finger resembles;

A plunging river is what the left ring finger resembles.

Qin tablature says,

Whenever the thumb goes outwards it is called dragging (托 tuo);

Whenever the index finger goes inwards it is called rubbing (抹 mo);

Whenever the index finger goes outward it is called picking out/arousing (挑 tiao);

Whenever the index finger arouses two or more connected strings it is called passing across (歷 li)

Whenever the middle finger goes inwards it is called hooking (勾 gou);

Whenever the middle finger goes outwards it is called scraping off (剔 ti);

Whenever the ring finger goes inwards it is called hitting (打 da);

Whenever the ring finger goes outwards it is called plucking/picking (摘 zhai).

| Poem of playing the qin, written by Yuan Junzhe 5 | See full page |

and the night is very peaceful.

A solitary man sits in a quiet room,

playing a jade-studded qin.

(The sounds) are fortuitous, with a spirit of harmony,

and the propitious phoenix seems to be dancing.

Jade blue heavens are peaceful,

the water-dragon hums.

Through the half-open curtain the bright moon can be seen,

there is a peaceful mood.

The tune is Bright Spring (Yang Chun),

it is a most ancient air.

The playing finishes but the player doesn't realize,

the stars have moved across the skies.

He is filled with the feelings of spring,

which completely penetrate his clothing.

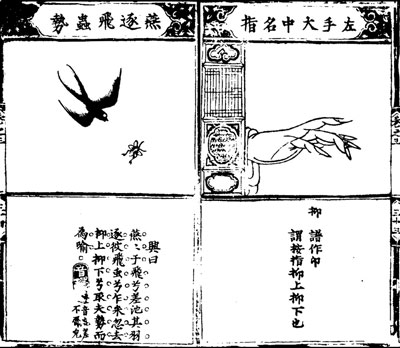

| (Hand Gesture Illustrations) 6 | Compare Taigu Yiyin (expand) |

The 33 illustrations (17 for the right hand, then 16 for the left hand) below are not numbered in the original: numbers are added here for ease of reference. None of the editions of this book has a title for this section. The tables of contents in QQJC, for both Taiyin Daquanji and Xinkan Taiyin Daquanji, call this section Hand Gesture Illustrations (手勢圖 Shoushi tu), and

QFTGYY has the same, so that title is used here. All illustrations consist of two parts but they are not identical: as the illustration at right, one of 33 (half of suoling is missing) from the edition in the National Central Library in Taiwan shows (expand), both the text and the image, though related, can be somewhat different. It seems that in the original each of these was on the same folio page, which meant that as traditionally bound they did not face each other. This is revised here so that on the left are the poetic evocations, which all begin "Xing says" (興曰 Xing yue"). Here "xing" refers to a brief poem.7 On the right are the explanations. In the original the commentary of course follows the traditional pattern of top to bottom and right to left, hence the 1.a. is on the right and 1.b. on the left.8 It is not clear why a number of important early techniques were not included here.9

The 33 illustrations (17 for the right hand, then 16 for the left hand) below are not numbered in the original: numbers are added here for ease of reference. None of the editions of this book has a title for this section. The tables of contents in QQJC, for both Taiyin Daquanji and Xinkan Taiyin Daquanji, call this section Hand Gesture Illustrations (手勢圖 Shoushi tu), and

QFTGYY has the same, so that title is used here. All illustrations consist of two parts but they are not identical: as the illustration at right, one of 33 (half of suoling is missing) from the edition in the National Central Library in Taiwan shows (expand), both the text and the image, though related, can be somewhat different. It seems that in the original each of these was on the same folio page, which meant that as traditionally bound they did not face each other. This is revised here so that on the left are the poetic evocations, which all begin "Xing says" (興曰 Xing yue"). Here "xing" refers to a brief poem.7 On the right are the explanations. In the original the commentary of course follows the traditional pattern of top to bottom and right to left, hence the 1.a. is on the right and 1.b. on the left.8 It is not clear why a number of important early techniques were not included here.9

| 1.b. In the manner of a crane dancing as a result of being startled by a breeze | 1.a. Right hand thumb 11 |

|

Xing says:

From myriad cavities there is furious howling.

Suddenly it cries out, startling people (in the area). The sound is mournful and fully developed. |

擘 Pi/bo (tear/thumb; compare 劈 pi) in tablature is written 尸

托 Tuo (drag) in tablature is written 乇 Pushing the thumb outwards from the body (or "inward"?), using half fingernail and half flesh is called bo (or bai). (The same, but) pulling the thumb inward (or "outward"?) is called tuo. Whenever utilizing a finger towards the body it is called "inward"; if towards the studs it is called "outward". All the examples use this terminology. |

| 2.b. In the manner of a visiting wild goose grasping a rush plant | 2.a. Right hand thumb and forefinger |

|

Xing says:

The cool autumn breezes suddenly arrive.

It can avoid going through the passes (in the Great Wall, which others cannot do) and abandon (the stick?). He transmits his sad sound, which moves people |

捻 Nian (pinch/snap) in tablature is written 念 nian :

Use two fingers to pinch and lift a string. When you let go, there will be a (snap-like) sound called nian.

(This sound is said to imitate that of a string breaking, especially when occuring at the end of a melody [examples

1 &

2, but

compare 3]).

|

| 3.b. Cranes call out in the shade | 3.a. Right hand forefinger |

|

Xing says:

Cranes Crying in Nine Bends of the Marsh. *

Simply let your fingers fly in order to attain this image. Realize the height and peaceful solitude in the melody.

(* Refers to the Shi Jing quote, not the melody.) |

抹 Mo (rub) in tablature is written 木

Pulling the forefinger inwards across a string is called mo. 歷 Li (pass across) in tablature is written 厂

拂 Fu (brush off) in tablature is written 弗

度 Du (cross) in tablature is written 广

擂 Lei (beat; sometimes 播 bo: shake) in tablature is written 雷 (番)

|

| 4.b. In the manner of the crane-like wild jungle fowl calling and dancing | 4.a. Right hand forefinger, middle finger and ring finger |

|

Xing says:

In the desert, people are at peace,

Wanting to know how this is related to the sound of the music, (we must) understand deeply the swift nature of the steps of this dance. |

鎖 Suo (chain) in tablature is written 巛

The forefinger does a tiao, mo and tiao, connecting 3 sounds in all; it's called suo (now usually mo-gou-ti). 反鎖 Fansuo (reverse chain) is written 反巛

短鎖 Duansuo (short chain) is written 矢巛

長鎖 Changsuo (long chain) is written 長巛 : first

tiao mo, then 4 sounds, (repeat twice?), then connect with 3 sounds (suo).

換指鎖 Huanzhisuo (change fingers chain) is written (see above)旨巛

|

| 5.b. In the manner of a lone duck turning his head towards the flock | 5.a. Right hand middle finger |

|

Xing says:

The lone duck turns its head towards the flock,

Using the purple haze to (hide as they) fly together, they fly around again and again in circles as they look downwards. |

勾 Gou (hook) in tablature is written ⼓ (see above) .

踢 Ti (scrape off) in tablature is written (see above) . 勾踢 Gouti in tablature is written (see above) Pushing the middle finger out across the string is called ti. Pulling out and pushing back as a pair is called gouti. 袞 Gun (should be 滾 roll/boil; 袞 is a tablature form): a connected ti on three or four strings is called gun.

|

| 6.b. In the manner of a dragon gripping the clouds | 6.a. Right hand thumb and middle finger |

|

Xing says:

The clouds have a dragon amongst them,

|

齊撮 Qicuo (evenly pinch) is written "(see image)" or "早"

(as here)

If you squeeze the 1st string together with the 6th string evenly as one sound it is called qicuo (repeated with different fingers in #7) 齪捉 Chuozhuo (grate and grasp) is written 足

|

| 7.b. In the style of a praying mantis grabbing a cicada. | 7.a. Right hand forefinger and ring finger |

|

Xing says:

The cicada's nature is that it is solitary and untainted (by the ordinary).

It is also said, The performance of qicuo followed by fancuo is very much like these movements. (See Cai Yong for a well-known cicada and praying mantis story.) |

齊撮 Qicuo (evenly pinch [repeats #6 but with different fingers])

反撮 Fancuo (unpinch) is written 反早 If the cuo is being performed on the 3rd and 5th strings, then the thumb pushes out (together with the) forefinger (as it) does a tiao on the 5th string. (At the same time) the ring finger performs a da (#14) on the 3rd string, making one combined sound. After this sound the thumb and ring finger will come together on the 4th string. As for fancuo, (if still on the 3rd and 5th strings) the 2nd finger performs mo on the 5th string and the ring finger does da on the 3rd string, making one sound. |

| 8.b. In the style of a crab walking 12 | 8.a. Right hand forefinger, middle finger and ring finger |

|

Xing says:

Crabs seem to come together then separate.

You can see the style it uses of turning up and down as it walks. This resembles the sentiments of the movements lun and li.

|

輪 Lun (revolving) in tablature is written (see above; also: 冂). Flex the three fingers and hold them in the vicinity of the 3rd and 4th stud. Then perform in succession zhai, ti and then li on one string. This is called lun.

If the tablature says "lunli the 7th and 6th strings", this means first to lun the 7th then li the 6th.

倒輪 Daolun (overturned revolving) is written (see above). Use three fingers to quickly mo, gou then da one string. This is called daolun. |

| 9.b. In the manner of a shaking a chain and ringing its bells | 9.a. Right hand ring finger, middle finger and forefinger |

|

Xing says:

A group of bells suspended from a rope.

Merely obtain this appearance in order likewise to shake the string. (The sound) naturally flows high and low, while extending outward to a great distance. |

索鈴 Suoling (roped bells*) in tablature is see above or 糸令

If you use the left thumb at the 7th stud pressed down** on the 7th, 6th and 5th strings, then do a lun going over everywhere, this is called suoling. |

|

10.b. In the manner of water from a spring

cascading in a deep valley |

10.a. Right hand forefinger and middle finger

13

(the explanations below are separated line by line) |

|

Xing says:

The empty valley is deep and serene.

Realize the sound according to this example. The die (duplicating) finger techniques all seem to be quite resembling this. |

分㳙 Fenjuan (split clarify) is notated 分厶 . First

mo then gou, putting the fingers down in the shape of 八 and it's called 厶 juan. 㳙 is written 厶 .

蠲 Juan (clarify) in tablature is written (see above *). 疊 Die (duplicate, repeat; the 田 on top can be written 厶) three fingers, pulling the string in as one sound; (also) written 厶 . 倚㳙 Yijuan (leaning clarify) is written 厶奇 (in GLS Kaizhi?) 半㳙 Banjuan (half clarify) is written 半奇 . First mo the forefinger; the middle finger then stops the string; there is only a little sound. This is called yijuan or banjuan; others are like this. 覆㳙 Fujuan (repeat clarify) is written 复厶 (or) 反厶. First gou then ti the middle finger, then mo tiao the forefinger as one sound; this is called fanjuan. 双㳙 Shuangjuan (paired clarify) is written 双厶 . 連㳙 Lianjuan (connected clarify) is written 車厶 . 疊㳙 Diejuan (duplicate clarify) is written 田厶 . First mo then gou; do it quickly, clearly distinguishing two sounds. This is called shuangjuan; it is also called lianjuan, and diejuan is the same. |

| 11.b. In the manner of wind sending of light clouds | 11.a. Right hand forefinger and middle finger |

|

Xing says:

Ranran rongrong,

One should make an example of the resemblance of the fingers' movements to the clouds. Do not make the sound too heavily. |

半扶 Banfu (half sustain) is written 半夫 .

The forefinger and middle finger, unequal in height, are pulled inward across two strings, making one (continuous) sound; this is called banfu. 全扶 Quanfu (fully sustain) is written (see above) *

(* Transl: This technique seems to be quite similar to juan. Wuzhizhai Qinpu says it is the opposite of lun.) |

| 12.b. In the manner of the male and female phoenixes calling together | 12.a. Right hand forefinger and middle finger |

|

Xing says:

The (female) phoenix flies about the high sentry posts

(In the same way you should) grip the two strings and pull them at the same moment. If it resembles this sound, it will be harmonious. |

圓摟 Yuanlou (round embrace) is written (see above).

爰摟 Yuanlou (leading embrace) is written 爰 ( 婁 ?) If, for example, you used the forefinger to execute mo on the 5th string, then with the middle finger you gou the 4th string (then with the forefinger mo or tiao the sixth string*), playing them evenly and clearly, making one sound, this is called "yuanlou". It is the same as what is called in Xi Kang's Rhapsody "pilou" (** 批摟 but 批 is written 媲 with 女 on the left replaced by 手: see 6/804). (* added by the translator to correspond with tablature as found in

SQMP, etc.)

|

| 13.b. In the manner of a fish shaking its tail as it swims | 13.a. Right hand forefinger and middle finger |

|

Xing says:

Thunder and rain act as explanations.

Using this as an example will bring out the right style. Join the fingers together and whirl them quickly. [Yin shi:] "Quickly" (瞥 pie) sounds like "inclined" (偏 pian), entering tone. |

撥剌 Bola* (shake and slash) is written (see above)

[Yin shi:] "Slash" sounds like "door screen" (闌 lan, entering tone). Two fingers together going out across a string is called bo.

|

| 14.b. In the manner of the shangyang bird, tapping and dancing | 14.a. Right hand ring finger |

|

Xing says:

There is a bird that only has one foot.

Bend the ring finger as you approach the string.

|

打 Da, in tablature written 丁 (see also #15)

摘 Zhai, in tablature written (see above) 打摘 Dazhai, in tablature written (see above) Pulling the string inward is called da.

(Transl: earlier explanations of da do not specify the finger. But note that here, although the finger is not mentioned, at left the finger is called 名指 mingzhi, short for 無名指 wuming zhi [no-name finger, i.e., ring finger], and the illustration above shows the ring finger executing the stroke.) |

| 15.b. In the manner of a supernatural tortoise coming out of the water | 15.a. Right hand forefinger and ring finger |

|

Xing says:

On its back a diagram is drawn out.

This (hunching and raising) should be compared to the motions tiao and da. It provides evidence that the former ancients were not improper. |

打 Da (hit) in tablature is written 丁 (see also

#14)

挑 Tiao (picking out/arousing) is written (compare li, now usually for multiple strings) Pull the thumb to stabilize the forefinger, which pushes the string outwards; this is called da. If the ring finger also does a da, it is called tiaoda. 打員 Dayuan (hitting in a circle: should be 打圓) is written 丁員 or (see above)

(* Transl: all three versions are different here, none making sense to me. My interpretation is 連作三挑 [instead of 絃],連作三勾 [others have 句], allowing the sequence to be, as is commonly understood, 挑六、勾三,挑六、勾三,挑六、勾三.) |

|

16.b. In the manner of a sea dragon intoning

|

16.a. Right hand forefinger and middle finger |

|

Xing says:

The dragon lives in a cave dwelling.

How can (the dragon) be compared with a supernatural being? Rather, in a hidden way it unites with the heart of the qin. [Yin shi:] "Hidden" means "secret". "Unites" means "harmonizes". (If) something "in a hidden way unites", (in fact it) secretly harmonizes. |

小閒勾 Xiao Jian'gou (short divided hook) is written (see above) or (also see above)

If you dayuan a stopped 3rd and open 6th string, then gou the 4th, da the 3rd and tiao the 6th, it is called jian'gou; if there is no dayuan, then it is no jian'gou, but simply gou and da. 大閒勾 Da Jian'gou* (long divided hook) is written (see above)

(* Transl: For da jian'gou, QFTGYY has only, "If (the dayuan?) has one sound (i.e., one phrase of the dayuan?) it is called xiao jian'gou; with two sounds it is called da jian'gou. |

| 17.b. In the manner of a hungry raven pecking at the snow | 17.a. Right hand forefinger, middle finger and ring finger |

|

Xing says:

Here there is a flock of birds, there footprints.

Accordingly if more than lightly playing... its manner is empty and slow.(?) |

單彈 Dantan (single play) in tablature is written (see above)

Hooking the thumb around the forefinger, then plucking outwards with this one finger is called dantan. 雙彈 Shuangtan (double play) in tablature is written (see above)

三彈 Santan (triple play) in tablature is written (see above)

|

| 18.b. In the manner of the supernatural phoenix grasping a letter in its mouth | 18.a. Left hand thumb |

|

Xing says:

Behold the phoenix.

The thumb is pressed down and the forefinger turned over. The others imitate this. |

按 An (press down; compare #s 22,

23 and 24, which refer to different fingers) in tablature is written 女

Use half flesh and half fingernail in pressing down on the string, as if trying to push right into the wood. Press down with unsuppressable force. If the thumb is pressed down near the 9th stud, the tablature is 大九. All others follow this example. |

| 19.b. In the manner of a howling gibbon climbing a tree | 19.a. Left hand thumb |

|

Xing says:

Look at that howling gibbon.

Heavily put the fingers into a small place, desiring marvelous speed in coming and going (on the string, as up and down the tree). |

猱 Nao (gibbon)14 in tablature is written 犭

Press down the thumb and take advantage of the sound (from plucking the string) by pulling out (towards?) the studs a little bit. Quickly return from (?) the stud to attain this sound. It is written nao because it resembles a gibbon climbing a tree, grasping on in order to climb, and crying out. [Yinshi:] Nao sounds like "clamor" (呶 nao); it is a kind of 猿 gibbon. 微猱 Weinao (small nao) is written 山犭

|

| 20.b. In the manner of an echo from an empty valley | 20.a. Left hand thumb |

|

Xing says:

The long whistling noise begins.

So it is when the ring finger is pressed down and the thumb executes a yan. You want these sounds to continue mutually (i.e., the resonance to continue?). [Yin shi:] "Foothill" sounds like "deer" (lu); it means the foot of a hill. |

罨 Yan (net, extend net, cover) in tablature is written 內 or 奄 or 电. First place the ring finger (for example) near the 10th position, then use the thumb to (cover as with a) "net" the 9th position, making a sound; this is called yan. Others are all the same (as in this position). [Yin shi:] "Net" (dict.: yan) is pronounced as 庵 "an" ("hut", but people today say "yan"), entering tone.

(Transl: My teacher said that with yan the thumb should be put down firmly but gently, avoiding the slapping sound one often hears, particularly from beginners.) |

| 21.b. In the manner of a solitary bird pecking on a tree | 21.a. Left hand thumb |

|

Xing says:

The solitary bird avoids people.

Make the sound xuyan according to this example. The resulting sound is like that tapping. [Yin shi:] "Grub" sounds like "jealous" (du). It is a wood bug. "Knock" (丁 usually ding but the dictionary also gives zheng) sounds like "wrangle" (爭 zheng). |

虛罨 Xuyan (empty covering) is written (see above).

Don't pluck (with the right hand) and don't set down (the ring finger as in the previous technique). Simply yan the string with the thumb, producing this sound; this is called xuyan. 虛點 Xudian (empty dotting) is written (see above).

|

| 22.b. In the manner of a beautiful oriole in a fragrant woods | 22.a. Left hand forefinger |

|

Xing says:

Look at the beautiful oriole in front of you.

睍睆 "Toufan" (see note below) is also the robust sound of putting down the finger in this way. It is also like the soft chirping of a bird in spring. [Yin shi:] "Tou" (normally xian) sounds like tou (head); "fan" (normally huan) sounds like "opposite" (fan). It is a warning sound. |

按 An* (press down) is written 女

Pressing the fleshy part of the forefinger down on the string is called "an". If it is in the 7th position the tablature writes 食七 or 人七. (手兜) Dou** (lift up, control) is written 兜 . Using the fingernail (of the left hand) to gou a string up so there is a sound is called dou. * 按 an is usually not written in the tablature: compare #s

#s 18, 23 and 24, which concern other fingers.

|

| 23.b. In the manner of a wild pheasant climbing a tree | 23.a. Left hand middle finger |

|

Xing says:

It is a pleasant time: see the wild pheasant.

This is the meaning to attain in comparison. Thus it is not something which can be described in writing. (* Transl: This last line has six characters (音清清而不疾), making it the only line in all the quatrains to have more than 4 [not counting 兮 xi].) |

按 An* (press down). Bend the thumb close to the palm, then stand (the middle finger) on its end. If the middle finger presses down in the 10th position, its notated as 中十 . The others are like this.

推起 Tuiqi (push up) is written 推己 (also 扌己)

* 按 an (see also #s 18, 22 and 24, which concern other fingers); no indication of tablature, perhaps because when it is used as here, with the 3rd finger, it is not written in the tablature |

| 24.b. In the manner of a phoenix combing its feathers | 24.a. Left hand ring finger |

|

Xing says:

There is a phoenix living in the wutong tree.

When the ring finger is placed down, the thumb is bent in. It is because of this mannerism that it is named. |

按 An* (press down). Bend in the thumb close to the palm, and press down with the fingers in this position. If the ring finger is pressed down on the 10th position, it is notated 夕十 . Others are all done the same way.

|

| 25.b. In the manner of the spotted leopard embracing its prey | 25.a. Left hand ring finger |

|

Xing says:

There is a leopard looking for a change.*

One should imitate this attitude when playing the sounds. Perhaps the relationship is in the actions of the (leopard and the qin player). * i.e., a change in the environment, indicating a foe or prey is nearby |

跪 Gui (kneel) in tablature is written 危 or 足 (see above)

and also 跪 (see also 拶對 zandui 15) Bend the ring finger and then place it on the string (so that it touches between the base of the fingernail and the knuckle). This is called gui. |

| 26.b. In the manner of a pigeon crying out to predict rain | 26.a. Left hand thumb and ring finger 16 |

|

Xing says:

The heavens are about to cloud over, and soon the rain will fall,

One should attain this image in playing duian. Use the singing quality of the sound and follow that |

對按 Dui'an (duplicated pressing down) is written 女寸

If the thumb is placed down in the 9th position and a sound is produced, and then (with the thumb still down) the ring finger is placed at the 10th position, and then the thumb executes a taoqi* (pulling up), this is called duian. Other examples are like this. * Also see 搯撮 taocuo; sometimes a distinction seems to be made between:

|

| 27.b. In the manner of a cicada singing in the autumn | 27.a. Left hand thumb, middle finger or ring finger |

|

Xing says:

With wings it makes sound.

Understand this sound of the cicada and then you can obtain this sound. This very same meaning is used to strive for it. |

吟 Yin (intoning) in tablature is written (今 or see above)

Putting down the finger so as to achieve the sound, then moving with a fine motion, not moving the finger beyond the position, is called yin. Sometimes one might use the fingernail, other times the flesh is used. If the thumb is put on the 1st string (or one string), then the nail is used. If it is put on the 2nd string (or two strings), the flesh is used. 細吟 Xiyin (fine intoning) is written (see above)

|

| 28.b. In the manner of fallen leaves following the flow of water | 28.a. Left hand thumb, middle finger or ring finger |

|

Xing says:

The fallen leaves follow the water flow;

In accordance with this manner, a comparison is obtained. If you can attain the meaning, you will understand. |

遊吟 Youyin (wandering intonation) is written (see above)

Press the finger down and make the yin sound as though it were waves flowing. Sometimes you might only go slightly beyond the (stated) position, other times you might go more, half a position . |

| 29.b. In the manner of a raven carrying a cicada as it flies | 29.a. Left hand thumb, middle finger or ring finger |

|

Xing says:

The cicada is in the raven's mouth.

This is made beautiful by going through the procedure. It is difficult to talk about and describe in detail. [Yin shi:] "Swallow" sounds the same as "visit" (ye). "Heads" sounds the same as "help" (zu/zhu). |

走吟 Zouyin (walking intonation) is written (see above)

Press down the finger and, following the sound, draw up (yin) a little bit, simultaneously doing both yin (vibrato) and yin (drawing up). Stop when the sound finishes. |

| 30.b. In the manner of a white butterfly wafted onto a flower | 30.a. Left hand thumb, middle finger or ring finger |

|

Xing says:

The white butterfly* wafted on a flower.

Obtain this meaning in order to allow it to be called "floating". It is like the light floating of the surface of the finger. * 粉蝶 : "pieris rapae" |

泛 Fan (floating; You Lan has 汎) is written 丿(but more horizontally)

Use the tip of the finger at the same time that the right hand strokes the string. It should float on top of the string, causing the string to move and sing. This is called fan. 泛起 Fanqi (floating begins) is written 丿己

泛止 Fanzhi (floating stops) is written 丿止.

|

| 31.b. In the manner of dragonflies flitting on water ("蜻蜓點水") | 31.a. Left hand forefinger, thumb or ring finger |

|

Xing says:

The dragonflies are countless.

This is like facing the studs and 互泛 "mutually playing harmonics" (?); this kind of thing is like that. [Yin shi:] "Floating ripples" (lianyi) means "ripples on the water". |

互泛 Hufan* (Mutually floating) is written (see above)

A floating sound performed with two fingers crossed over is called hufan. * The original has 牙泛 yafan ("tooth float", or it could represent the sound "ya"), perhaps a misprint, as it does not seem to make sense. Could it mean playing two notes simultaneously? Since I have never seen this figure in early tablature, it is difficult to verify. |

| 32.b. In the manner of a cicada calling as it passes a branch | 32.a. Left hand thumb, middle finger or ring finger |

|

Xing says:

The cicada is elevated;

(Like a cicada) suddenly feel alarm and pull away. Stretch out the sound, without stopping the sound which continues after. [Yin shi:] "Outer layer" (dict.: shui) sounds like "retreat" (tui); "shed" means "cast off". "Outer layer" means "exuviae". * "indicating that it has intelligence" |

引 Yin (drawing) is written 弓

Put down (a left) finger and obtain a sound, draw upwards; this is called yin. 注 Zhu (flowing) is written 主 (or 氵)

|

| 33.b. In the manner of a swallow grabbing a flying insect | 33.a. Left hand thumb, middle finger and ring finger |

|

Xing says:

The swallows are flying all around.

Retreat and advance as you push upwards and downwards. Obtain this and use it as an example. [Yin shi:] "Different from" sounds like "blemish" (疵 ci). Different from their feathers: not arranged in their appearance. (?) |

抑 Yi* (push) is written 卬 .

This means press down the finger, pushing upwards, then pushing back down. * Elsewhere this is called 迎 ying (welcoming). |

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

1.

Folio 3 (complete) : Hand Gesture Illustrations (QQJC I/53-70;

30 Volume edition I/63-80)

Such hand gesture illustrations were quite common in early handbooks but gradually disappeared (see further).

As for those here, the earliest surviving ones, in the 1970s, when I was studying guqin in Taiwan with

Sun Yu-ch'in, I made a rough translation of this passage from a copy of Taigu Yiyin preserved in Taiwan and included by Dr. Tong Kin-Woon (TKW) in his Qin Fu (QFTGYY), pp. 55 - 72; it is here modified according to the mostly identical passage in Taiyin Daquanji printed in QQJC 2010 edition Vol. I/63 - 80), referred to by TKW as the "Yuan Volume" (see his #6), after its supposed editor, Yuan Junzhe. When putting it online I tried to make corrections, but a number of passages still elude me.

(Return)

2.

Explanations by translator

See comments concerning the structure of the original text.

(Return)

4.

辨指 Bian Zhi

As the image shows, these were originally written together.

(Return)

5.

Poem of playing the qin, written by

Yuan Junzhe

This poem by Yuan Junzhe is not in the Zhu or Yuan volumes, so it is copied here from the Taigu Yiyin in the National Central Library, Taiwan; it is also in QFTGYY, p. 56. It is a shi with 8 lines of 7 characters each, the rhyme scheme being ab, cb, db, eb.

(Return)

6.

33 pairs of illustrations

Qinshu Daquan,

Folio 9 also has the same 33 pairs of illustrations as here. As with QFTGYY, the Zhu volume and the present Yuan volume, they are all in the same order (first 17 for the right hand, then 16 for the left hand), with the same images, though they may be drawn differently and the text is also somewhat different (the latter two texts including some additional finger techniques within some of the illustrations). In QFTGYY, TKW has numerous comments pointing out the differences in the texts.

(Return)

7.

Xing (興)

All of the left hand commentary begins, "Xing says" (興曰 Xing yue). Here xing (4th tone) refers to a form of indirect metaphor or simile, first found in the Book of Poems. ICTCL, p. 693, etc., compares xing to 比 bi, which is a direct metaphor or simile. All of the xing here for right hand techniques are 4 x 4 (four character lines x 4) except for #6, which doubles this (i.e., is 4 x 8) and also adds a 兮 xi at the end of the first, third, fifth and seventh lines. The xing for the left hand techniques are also generally 4 x 4, with QFTGYY, the Zhu and the Yuan editions sometimes differing on whether there is a xi at the end of the first and third lines. For some reason #23 adds two characters in the 4th line. In most cases the xing is followed by a brief comment.

(Return)

8.

Symbols explained through images

It is not always simple to compare symbols in the four handbooks considered here: only the incomplete

Taigu Yiyin has its own table of contents. Towards the end of the second folio (see QQJC 2010 edition, I/26) it lists two sections (both missing), one called "17 right hand gestures of appearance and method representations" (右手勢形法像十七條), and one called "22 left hand gestures of appearance and method representations" (左手勢形法像二十二條). Perhaps "22", is a mistake: none of the Ming handbooks has so many sketches -- in fact they are quite uniform about having the same illustrations. Briefly, the other Ming dynasty handbooks with sketches have the following:

- All 33, as pairs in the same order: Fengxuan Xuanpin, Qinshu Daquan and Qinpu Zhengchuan

- The same except they put the hand techniques and nature representations inside their illustrations: Wenhuitang Qinpu and Sancai Tuhui

- Same pairs of illustrations and very good sketches, but omitting most of the text: Yangchuntang Qinpu

- Chongxiu Zhenchuan Qinpu and Qin Shi both omit one of the left hand 32 illustrations and have sketches only of hand techniques; they have the names of the nature representations, but not the sketches.

It should be remembered that these diagrams, as well as the finger explanations in general, were mostly just copied down from handbook to handbook. They thus speak more of the continuity of the tradition rather than fully reflecting the differences of interpretation that may have developed over time and/or with specific players.

(Return)

9.

Symbols not included here (for finger positions note also the

switch to a decimal system)

Van Gulik, Lore, pp. 122 - 136

(.pdf), explains 54 symbols as part of a section called The Symbolism of the Finger Technique. Some of the techniques explained there, and also found in early tablature but not included with the above illustrations, include:

- 綽 chuo, usually written 卜 or 卜 over 日 (see upper right of chuo)

Play a note as you slide up to it; opposite of zhu. This technique is quite often found in tablature, but today it is extremely common among many players, often added when not called for in the tablature. My teacher said this was because on the long surface of the qin it is difficult always to have to put the finger down in precisely the correct position. It can thus easily become more of a cliché than a true ornament. - 撞 zhuang,

usually written 立

A quick left hand (usually thumb) slide up and down.

(By extentions, also not explained is 雙撞 shuang zhuang, in which the up and down motion is repeated.) - 進復 jin fu, usually written 隹 plus the top of 复

A slower left hand slide up and down- 分開 fenkai, usually written 八 over 开

For example, do a mo with the left thumb in a certain position; after striking the note slide the thumb up, then do a zhu back to the original position as you do a tiao.- 往來 wang lai, usually written 彳來

After striking a note with the right hand, the stopped left hand finger slides up and down twice- 放合 fang he, usually written 方合

After the right hand strikes a string with a left hand finger stopped in a certain position, the left finger pulls and releases the string, making a second sound that is simultaneous with a sound made by the right hand striking another string. - 分開 fenkai, usually written 八 over 开

Also not included with the old Taiyin Daquanji/Taigu Yiyin illustrated instructions are the following, beginning with the shorthand forms used for the four fingers of the left hand, then going on to the longhand forms of various instructions that do not lend themselves to images.

- 大 for 大指 da zhi (thumb),

- 人 for 食指 shi zhi (index finger),

- 中 for 中指 zhong zhi (middle finger) and

- 夕 for 無名指 wuming zhi (ring finger).

- 不動 budong (don't move; a left finger stays in the same position from one note to the next)

- 如一 ru yi ("as one": play two notes simultaneously)

- (從頭)再作 (cong tou) zai zuo ([from the beginning, or another indicated point] play again)

- 再二作 zai er zuo (play twice again: could mean play a total of three times, or play again for a second time)

- 從 ⁊ ("from the symbol ⁊ "; used together with previous to show where repeat begins

when tablature written horizontally left to right ⁊ may be be reversed:「 )- 急 ji (quickly)

- 慢 man (slow; also 入慢 ru man: become slow)

- 少息 shao xi (short rest)

- 入慢 ru man (slow down)

- 至 zhi (to)

- 如一 ru yi ("as one": play two notes simultaneously)

Most of these are explained under the non-illustrated instructions that begin here, but for other sources see also

this list and its related

footnote.

(Return)

11.

擘/劈 (bo/pi) vs. 托 tuo: in/out?

(image 1)

It seems that there has always been confusion about which of these two thumb strokes goes inwards and which does outwards. This can readily be seen in the varying finger technique explanations here in Taiyin Daquanji. Thus,

- The instructions above have 擘/劈 (pi/bo go outwards while those here, attributed to 劉籍 Liu Ji (10th c.?) have it come inwards.

- The same instructions above have 托 tuo come inwards while those here, attributed to Liu Ji have it go outwards.

It is not clear how these two became reversed, but the example of the earliest surviving melody, Jieshi Diao You Lan and its supposedly associated Wusilan Finger Technique Explanations might be instructive.

Among the Wusilan explanations of

basic strokes, it has no mention or examples of 托 tuo, only of 擗 pi. Here the

explanation for pi says the thumb should go outwards. However, you can see there a list of the eight examples of 擗 pi (written 擘) in the written score, and all of them will most naturally be played inwards.

(Return)

12.

Revolve (輪 lun), described as crab walking (蠏行 xie xing)

(image 8)

The description here perhaps suggests that the crab in question is a land crab (I am not familiar with the habitat of the "蟊 rice-eating grub").

The technique 輪 lun may also be described as 摘剔挑 zhai ti tiao, which has the same meaning of right hand fourth, third then second finger plucking outwards. In some cases the tablature calls for the three notes to be played with the left hand fingers also "revolving", stopping the string with the second, third then ring fingers, all at the same position. There is an example near the beginning of the 1425 Meihua Sannong.

As for 倒輪 daolun, I have not yet seen this in early tablature, but there is tablature that writes out the technique. For example, near the beginning of Section 7 of the 1525 Feng Qiu Huang a phrase begins with the right hand techniques mo gou da. Here the left hand corresponds by stopping the string with the second, third then ring finger, as described above. But here, instead of calling this 倒輪 daolun, there is the explanation "a big crab walking" (大蠏行 da xie xing).

(Return)

| 13. Juan: 蠲 or 㳙/涓/厶 (image 10) | juan 蠲 㳙 / 蠲 |

Juan seems usually to be said to consist of a rapid mo then gou on one string, but it may be on more than one string, in which case typically one might either mogou the first string then the second, or mo the first and second, then gou the first and second. In the two examples given here at right, from Dun Shi Cao and

Guangling San (the first two melodies in Shen Qi Mi Pu) the Guangling San example clearly shows a 厶 juan applied to one string while the Dun Shi Cao example, using a shorthand form not available by computer, has a juan over two strings. Because it is followed durectly by a 全扶 quanfu (on strings 3 and 4) my assumption is that it is intended to be in contrast with juan, so juan is played twice, first on string 1 then on string 2. (In the Guangling San example 厶 seems to be followeed by two yijuan, further explained in this footnote)

Juan seems usually to be said to consist of a rapid mo then gou on one string, but it may be on more than one string, in which case typically one might either mogou the first string then the second, or mo the first and second, then gou the first and second. In the two examples given here at right, from Dun Shi Cao and

Guangling San (the first two melodies in Shen Qi Mi Pu) the Guangling San example clearly shows a 厶 juan applied to one string while the Dun Shi Cao example, using a shorthand form not available by computer, has a juan over two strings. Because it is followed durectly by a 全扶 quanfu (on strings 3 and 4) my assumption is that it is intended to be in contrast with juan, so juan is played twice, first on string 1 then on string 2. (In the Guangling San example 厶 seems to be followeed by two yijuan, further explained in this footnote)

The explanations for the different forms of juan can be confusing, starting with why there are two different characters though they appear to describe the same techniques. Because neither the You Lan tablature nor the Wusilan Fingering Explanations include 㳙/涓, one might guess it came later. Since both 㳙 and 厶 are easier to write than 蠲, this might also suggest 㳙 is a later form, though there are no direct historical statements to this effect.

One of the practical tasks has been to determine such issues as whether or how successive juan (or a 連蠲 lian juan) may differ from 全扶 quanfu or from successive 半扶 banfu (image 11). This distinction does not seem to be made clear throughout the various juan explanations such as in

Wusilan Zhifa Shi as well as in the others collected in Taiyin Daquanji here and here.

(Return)

14. 猱 nao (my teacher pronounced this "揉 rou", rub/twist; image 19). The original of the accompanying explanatory verse is,

欲上不上,其勢逐逐。

In addition to those included above, some other types of 猱 nao can also be found in early handbooks such as Shen Qi Mi Pu. Most common is 撞猱 zhuang nao, as follows.

| 撞猱 Zhuang nao |

To my knowledge, although this term is quite common in Ming dynasty handbooks, it is introduced in only two of them:

To my knowledge, although this term is quite common in Ming dynasty handbooks, it is introduced in only two of them:

- Fengxuan Xuanpin (1539; II/18): 按指承声,一上,一下

Slide up and down (while doing vibrato?) - Huiyan Mizhi (1647; X/22): 撞猱也,音後一撞,向徽下急搖動,用在曲慢之時,須要潔淨。按準律呂,故云,撞猱行走怪支離。

Do a zhuang and shake quickly as you return to the original position. Do it during a slow passage, do it cleanly, and it should fit into the modality....

My personal interpretation is similar to the latter. However, considering how common this technique is in Ming dynasty handbooks (see, e.g., comments connected to Guangling San and a Japanese handbook), it is quite strange that it is not more commonly explained. It also has no clear antecedent in early finger technique explanations, though personally I have interpreted the 再臑 zai nao that occurs 5 times in You Lan to be similar to my understanding of zhuang nao.

To sum up my interpretation, the available descriptions for both zhuang nao and zai nao are so vague as to allow a number of interpretations. It is thus perhaps questionable to select a descriptions on the basis that it could fit both terms. However, it is a technique that I find quite both pleasing and appropriate to the music in question.

(Return)

15.

跪 gui (kneel) vs. 拶對 zandui (image 25)

With gui the curled left ring finger can also stop the string using the fingernail; this is especially true if the shape of the finger in between the nail and the knuckle is concave, in which case one cannot get good contact pressing the finger down in that area in between. In any case, pressing down with the nail usually involves developing muscles in the left ring finger, while pressing down with the flesh may require developing a callus, especially if sliding is involved, as it may in particular be with zandui.

拶對 zandui (12359.2 拶指:舊時酷形之一 Punish by squeezing the fingers: in olden days a cruel form of torture)

(Return)

16.

Left hand thumb and ring finger (image 27)

This entry, 對按 duian, makes no mention of 對起 duiqi, which is much more commonly used in tablature; in qin songs 搯起 taoqi, used here to describe duian, seems sometimes to be suggest a contrast with duiqi. Further details are as follows:

- 對按 duian vs 對起 duiqi

The explanation above says that to do a duian the ring finger is placed down then the thumb does a taoqi, i.e., it pulls the string upwards. Descriptions of duiqi are usually the same as duian (see, e.g., 1539 at II/18 and II/55). However, in qin melodies with lyrics the pairing is sometimes different, with duiqi sometimes having one (on the left hand pluck) or two characters (the first one added to the previous note, the second to the left hand pluck), while taoqi may have only one or none at all. However, there does not seem to be consistency on this. - 搯起 taoqi (pull out and up)

As mentioned, the explanation is virtually the same as that for duiqi: first press down on a string with the left ring finger, then make a sound by plucking upwards with that finger. However, as will be seen below with taocuo, taoqi by itself may suggest a left hand pluck on an open string. Note also the comment on pairing characters in qin melodies with lyrics.

In addition, the following techniques also involve the left ring finger being left in place while the thumb does the plucking:

- 搯撮 taocuo (aka 掐撮 qia cuo)

In later tablature 搯起 taoqi (pull out and up) often involves only pressing down on a string with the left hand ring finger, then plucking upwards with that finger; the pitch is that of the open string. This then contrasts with the 搯 tao technique in which the left ring finger remains in place while the left thumb plucks the same string, the pitch being determined by the position of the ring finger; this tao often follows a 罨 yan (cover): with the ring finger in place the left thumb "covers" (presses down on) the string, making a light sound, then the thumb plucks up (tao), causing another sound. These two sounds (yan then tao) are in turn commonly combined with 撮 cuo to make 搯撮 taocuo: with the left ring finger stopping a string the left hand thumb performs the yan then tao followed by a cuo on two strings, one stopped by the ring finger, the other an open string. Regarding the pitches there may be some uncertainty because, whereas the position of the left right finger is specified that of the left thumb is not: is the upper pitch always a tone above the lower one, or must its pitch be pentatonic? For example, if the left ring finger position produces the relative pitch 5 it is clear that the thumb position will produce 6, but if the left ring position produces 6 should the thumb press down so as to produce the sound 7 or should it stretch higher to produce 1?搯撮三聲 taocuo san sheng (aka 掐撮三聲 qiacuo sansheng)

This technique is an expansion of this 搯撮 taocuo, usually following a cuo on two strings, one stopped with the left ring finger as described above. First the left hand follows this cuo with the taocuo (yan, tao then another cuo), then the left hand does a double yantao (yan tao yan tao ) followed by a final cuo. This is presumably called sansheng (three sounds) because the yan and tao are each done three times. There are other ways to do this technique, but this is the way I learned it. There may again be the uncertainty described above of the pitch produced by tao.

Return to Taiyin Daquanji index page,

to the annotated handbook list

or to the Guqin ToC.