|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Taiyin Daquanji ToC Folio 3 Folio 4: ToC 1 / 2 / 3 / 4 / 5< /A> / 6 / 7-21 / Folio 5 ToC | 網站目錄 |

|

Taiyin Daquanji

1

Folio 4, Part 6: Qin Critique Chapter 琴議篇 Qin Yi Pian (QQJC I/83) 2 |

太音大全集

卷四,己:琴議篇 |

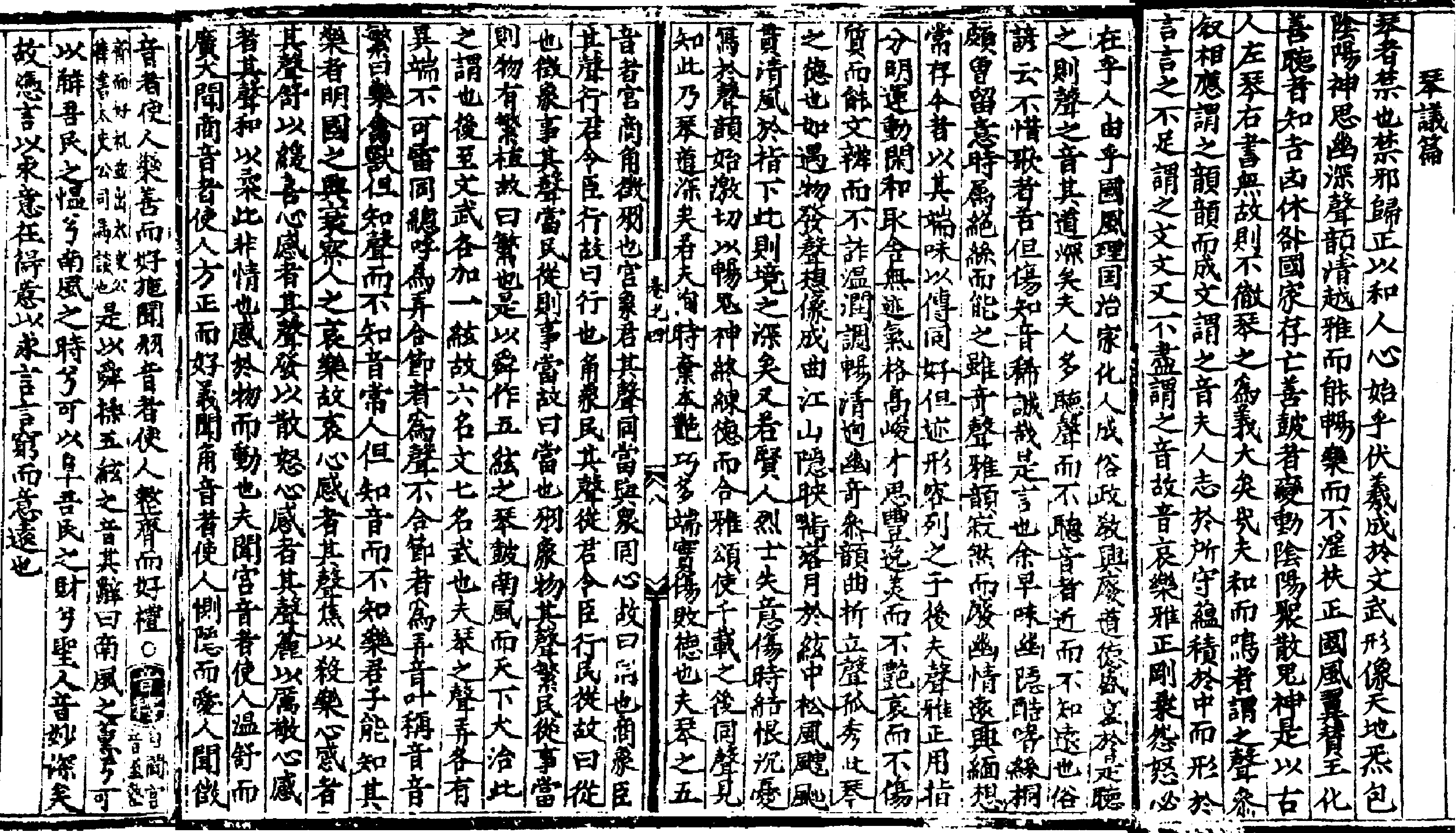

| Qin Yi Pian; QQJC I/83b-84a |

Part Six: Qin Critique Chapter

Part Six: Qin Critique Chapter

琴議篇 Qin Yi Pian

This essay, elsewhere attributed to Liu Ji, is discussed by Xu Jian in QSCB. (Corrections) here in the text come from other editions.

“Qin" signifies "restraint", meaning it restrains evil and returns one to propriety, harmonizing the human heart (see Huan Tan, Xin Lun.

始手伏羲,成於文、武。

It began at the hand of Fuxi then was perfected by Wen Wang and

Wu Wang.

形像天地。炁包陰陽。

Its form resembles Heaven and Earth; its vital energy encompasses yin and yang.

神思幽深。聲、韻清越。

Its spirit and thought are profound; its sound and sonority are clear and far-reaching.

雅而能暢,樂而不淫揺。

It is refined yet expressive, joyous but not indulgent or wavering.

扶正國風,翼贊王化。

It upholds the righteousness of national customs and assists in the transformation of the ruler’s virtue.

善聽者,知吉凶休咎。國家存亡。

One who listens well can discern fortune and misfortune, prosperity and calamity, as well as the survival or downfall of a nation.

善豉者,變動陰陽。聚散鬼神。

One who plays well can influence the movements of Yin and Yang and summon or disperse spirits and deities.

是以古人左琴、右書。無故則不徹。琴之為義大矣哉。

Therefore, in ancient times, scholars placed a qin to their left and books to their right, and they would not play it without purpose. How great is the significance of the qin!

Much of the information here is also elsewhere in early qin handbooks.

Go to text on next page.

Or return to the Folio 4 Table of Contents

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

1.

太音大全集 Taiyin Daquanji Folio 4, Part 6 (QQJC 30 Volume edition I/83; QF/77-78)

See also the Comment on the different editions.

(Return)

2.

Explanations by translator

See comments concerning the structure of the original text.

(Return)

Return to Taiyin Daquanji