|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Qin Shi Xu Qin Se He Pu Yi Liu Zheng Wuzhizhai Qinxue Mishu | 首頁 |

|

Qing Rui

1

- Qin Shi Xu #308 2 |

慶瑞

琴史續 #308 Qing Rui holding a qin ca. 1870 3 |

Qing Rui (1816-1875), a Manchu from Heilongjiang, served as a government official (often military) in various places in China. This includes some time in Hangzhou, where from about 1836 to 1939 he studied guqin from Li Chengyu,4 a master of the Guangling qin school.5

Qing Rui (1816-1875), a Manchu from Heilongjiang, served as a government official (often military) in various places in China. This includes some time in Hangzhou, where from about 1836 to 1939 he studied guqin from Li Chengyu,4 a master of the Guangling qin school.5

Details of Qing Rui's official marriage are uncertain other than that by his wife, named 聶格爾氏 Nie Ge-er (1820 - ?), he had two sons, but that none of them is known to have had any connection with Qing Rui's musical activities.

At age 27 (around 1843) Qing Rui moved to Canton (Guangzhou), serving as a goverment official in various places including Haikang in the far south of Guangdong (perhaps including Hainan).6 Then around 1862 李芝仙 Li Zhixian (1842 - 1908) became his "local wife".7 She is said to have inherited the Lingnan style of playing, which would have been rather different from the Guangling style Qing Rui had previously learned. Together they shared an interest in both qin and se, and together and separately they taught a number of students. After Qing Rui died in 1875 she continued to teach, and it seems quite likely that overall her "Lingnan style" became dominant.8

During the years 1862 to 1908, when Li Zhixian died, Qing Rui and Li Zhixian personally taught qin to family members in particular, starting a line of players that has extended from father through son down to the present. This so-called line of the Rong Family Tradition is thus as follows:

- 容慶瑞 Rong Qing Rui (1816-1875); because of the family connection the family name Rong is sometimes given to Qing Rui himself.

- 容葆廷 Rong Baoting (1862 - 1920); only son of Qing Rui and Li Zhixian, he is said to have learned qin from both of them.

- 容心言 Rong Xinyan9 (1884 - 1966); he followed his son to Hong Kong; his students included 饒宗頤 Rao Zongyi and Lo Ka-ping.

- 容思澤 Rong Size11 (Yung Sze-chak; 1931 - 2001); in the 1950s he moved to Hong Kong.

- 容克智 Rong Kezhi (Yong Hak-chi or Hammond Yong;12 teaches in Hong Kong and in 2015 published the 香江容氏琴譜 Xiangjiang Rongshi Qinpu.

- 容葆廷 Rong Baoting (1862 - 1920); only son of Qing Rui and Li Zhixian, he is said to have learned qin from both of them.

Further regarding the style inherited by Rong Baoting, presumably Li Zhixian's influence was most important, since Qing Rui died when Rong Baoting was just 13 hears old. In addition, though, Qing Rui's biography in Qinshi Xu, partially translated below, says that in Guangzhou he had as a house guest the qin player 周竹舲 Zhou Zhuling;13 it is not clear whether Zhou studied with Qing Rui, taught him or simply enjoyed his playing; it is also not clear from this whether Zhou taught others there. The biography does mention a Dream Fragrance Garden (夢香園 Meng Xiang Yuan).14

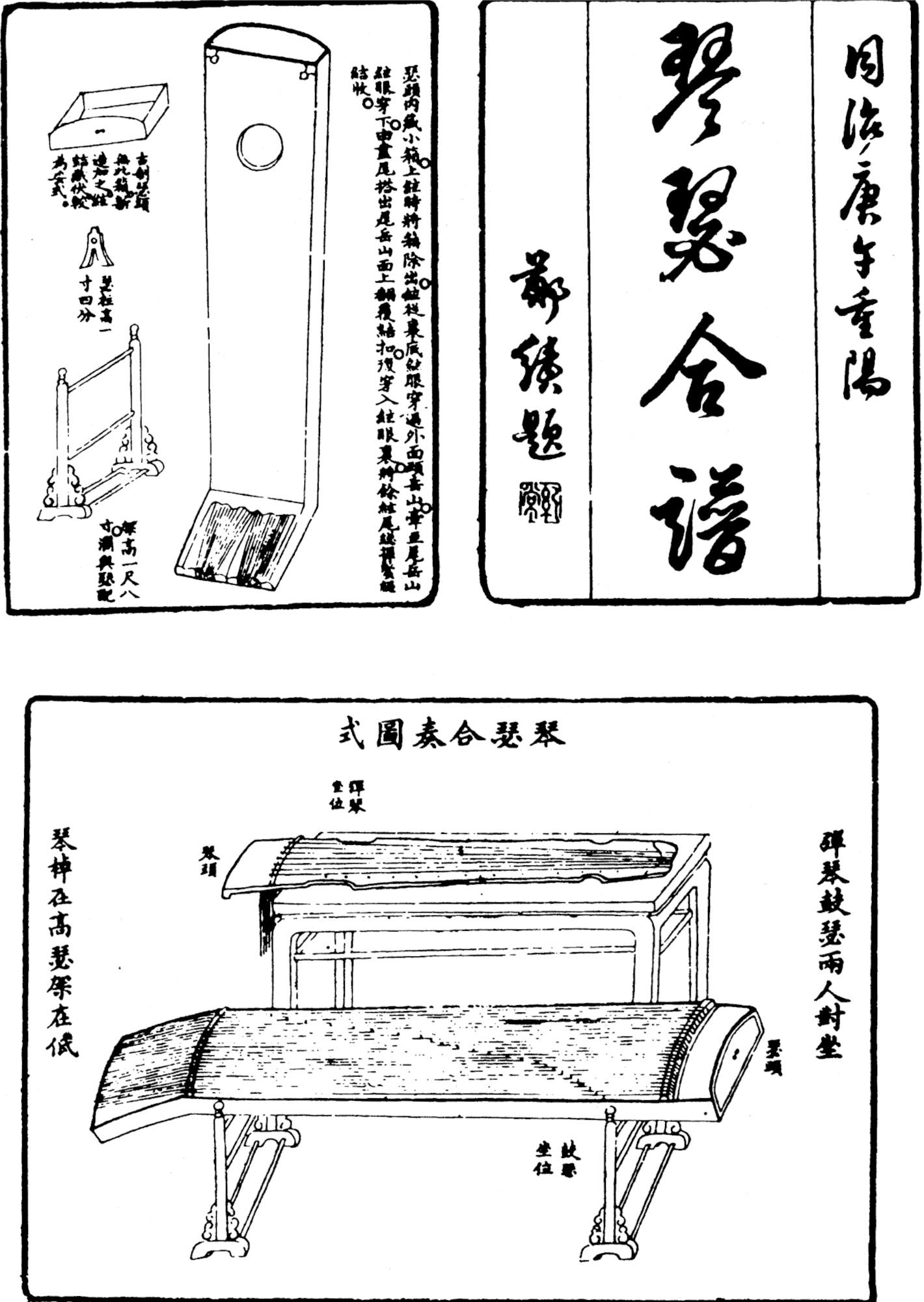

Some of Qing Rui's art was handcopied in tablature preserved within the Rong family. In addition, in 1870 Qing Rui himself produced a Handbook for Playing Qin and Se Together (琴瑟合譜 Qinse Hepu);15 its eight qin melodies with se accompaniment are listed in Appendix I below.

As for other qin players in Guangzhou outside Qing Rui's family but considered to have been his students, one of these, 孫寶 Sun Bao, compiled 以六正五之齋琴學秘書 Yi Liu Zheng Wuzhizhai Qinxue Mishu (1875).16 Its contents are listed in Appendix II below. Of its 21 pieces, six are the same titles as pieces in Qinse Hepu, but with mostly different versions of those melodies.

Of Qinse Hepu R.H. Van Gulik wrote the following (Lore, p. 9 fn.; Romanization changed):

Here it should be pointed out that simply because the qin and se scores were written as though they should be played in unison this does not mean players would have to play that way - or even that it was intended they play that way. It could also be that the intention was for each player to learn the basic melody by playing their respective tablature, but that when they actually played together they would be free to do so in, for example, a

heterophonic manner. The extent that they could do this would have to do with their skill and experience.

In Guangzhou Qing Rui also made friends (through Li Zhixian?) in the local Lingnan school. He thus became familiar with their signature handbook, Wuxue Shanfang Qinpu (1836), as well as with the rather speculative Gugang Yipu, a handbook said to have preserved ancient melodies brought to the Pearl River delta at the end of the Song dynasty. However, he and is descendants continued to consider themselves to be Guangling School.

Qing Rui's biography in Qinshi Xu

....At times at his Dream Fragrance Garden he would play se while his house guest Zhou Zhuling played qin. Guests who heard this all praised its beauty.

The middle part, not yet translated, mostly concerns se.

1.

慶瑞 Qing Rui references

2.

Original

3.

Image: Qing Rui holding qin

4.

李成宇 Li Chengyu (also written zhixin?)

5.

Guangling Qin School (廣陵琴派 Guangling Qinpai)

6.

廣東海康 Haikang in Guangdong

This entry begins and ends as follows:

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

Style name 有年 Younian, nickname 輝山 Huishan. In addition to the Qin Shi Xu biography above, primary available reference materials are the biographical essay by Tong Kin-Woon in his Qin Fu and materials in Hammond Yung's 香江容氏琴譜 Xiangjiang Rongshi Qinpu.

(Return)

9 lines; the source given is Chunhu Manlu.

(Return)

A copy of this photo was included with the essay about Qing Rui in Tong Kin-Woon's Qin Fu.

(Return)

Some of the melodies included in 香江容氏琴譜 Xiangjiang Rongshi Qinpu are attributed to Li Chengyu. No further information as yet other than that he was a 廣陵派 Guangling School qin player living in Hangzhou, and that his skills were learned from 徐越千 Xu Yueqian and 周子安 Zhou Zi'an. However, nothing further seems to be known about any of them. Apparently, though, this is where Qing Rui first became interested in se with qin.

(Return)

This school (see in chart) was founded in Yangzhou at the beginning of the Qing dynasty by Xu Changyu and others.

(Return)

Haikang is basically the peninsula in southern Guangdong province facing Hainan island (which may at that time have been included in its jurisdiction).

(Return)

| 7. 李芝仙 Li Zhixian (1842 - 1908) | 李芝仙 Li Zhixian |

Li Zhixian was from 番禺 Panyu (or Punyu), then a village but now an urban area on the south side of Guangzhou. There she is said to have learned the Lingnan style as transmitted through the

Gugang Yipu. However, details of this are uncertain.

Li Zhixian was from 番禺 Panyu (or Punyu), then a village but now an urban area on the south side of Guangzhou. There she is said to have learned the Lingnan style as transmitted through the

Gugang Yipu. However, details of this are uncertain.

When she was 20 Li Zhixian became the "local wife" ("側室", often translated as "concubine" but suggesting she was more than that) of Qing Rui, who by then had begun to spend less time traveling and more time in Guangzhou. It is not clear to what extent she would have adapted Qing Rui's style of qin play. Contemporary texts speak not so much about this as about their joint interest in playing qin and se together. It was a few years after they combined forces that he published his 琴瑟合譜 Qin Se He Pu (QQJC XXVI; 1870).

In any event Li Zhixian taught the qin to Rong Baoting (1862 -1920), the only child that she had with Qing Rui, as well as to Baoting's son Rong Xinyan (1884-1966) and grandson, Rong Xinyan. Thus began the "Rong family style" that has come down to the present.

(Return)

8.

Teaching in Guangzhou

See further above. In addition to 晉齋孫寶 Sun Bao did this later include Ye Shimeng?

(Return)

9.

容心言 Rong Xinyan (1884 - 1966)

He wrote this essay.

(Return)

11.

容思澤 Rong Size (Yong Sze-chak; 1931 - 2001)

His recordings with the 2015 publication come from previously published ones such as this one.

(Return)

12.

Hammond Yong (容克智 Yong Hak-chi [Rong Kezhi])

Hammond, who learned qin from his father 容思澤 Yong Sze-chak, actively teaches today. He and his group of students have also been active in both making qins and re-making standard factory qins. Hammond now plays solely with silk strings; he has several recordings posted on YouTube (go to the site) and in 2015 published Xiangjiang Rongshi Qinpu (further below).

(Return)

13.

Zhou Zhuling 周竹舲

No further information as yet.

(Return)

14.

Dream Fragrance Garden (夢香園 Meng Xiang Yuan)

This was a villa in Guangzhou belonging to 鄭績 Zheng Ji, a well-known local painter who wrote a foreword for 琴瑟合譜 Qin Se He Pu.

(Return)

15.

Qing Rui's Tablature for Qin and Se Together

(琴瑟合譜 Qinse Hepu)

Zha Fuxi's Preface to this handbook says (XXVI/iii),

During the Yuan dynasty, Xiong Penglai (1246-1323) wrote a se handbook in which he assigned the twelve lü (pitches of the scale) to the thirteen strings of the instrument. This system, however, was impractical, and it was ignored from the start. Then in the early Qing dynasty, in Cheng Xiong’s (Songfengge) Qin-Se Pu was published with se tablature appended to the piece Da Ya (Great Elegance), but it was just one piece. Similarly, Fan Chengdu’s Qin-Se He Pu contains only a few pieces, and those are all quite simple and practical; their string assignments and tonal layout are so straightforward that they need no explanation. Thus it was not until the ninth year of the Tongzhi reign (1870, gengwu year) that Qingrui’s Qin-Se He Pu appeared, establishing a more structured yet simple method for playing the se.

| Explanation of se tablature (expand) |

Qingrui, a native of Heilongjiang, styled Huishan, was serving as an official in Guangdong when he compiled this Qin-Se He Pu (see XXVI/160 [transcription] and sample page below). Here he arranged the five tones — gong, shang, jue, zhi, yu — from top to bottom in five groups (octaves?), arranged across the se’s twenty-five strings, using the five symbols 𠂊山刀宀口 (宀=宮, 口=商, 𠂊=角, 山=徴, 刀=羽) to represent the five tones, and numerals 一二三四五 (1 through 5) to indicate their pitch grouping (i.e., which octave the relative pitches in the order 宮商角徵羽 are in). The se tablature is laid out side-by-side with qin tablature. His method is quite straightforward and is explained using just two basic rules (fanli).

在這部書裏,他總共只用了八個古琴曲寫成瑟譜。這八個古琴曲,也多半是較簡單的。只是其中他把琴譜原來「不轉絃熒調」的《洞庭秋思》在琴上改爲慢一三六絃,同時還必需將瑟柱下移;又在彈《塞上鸿》時,也把瑟的羽絃移高一律。可見他的瑟譜對於琴調的變化,並無駕之法,因而這個瑟譜並不能解决全面與琴合奏的問題。這和《琴簫合譜》的簫終於合不了,而把它推到曲的作法不對的問題上去,是一樣的煩惱。但慶瑞究竟比周顯祖的《琴簫合譜》來得老實。

In this book, he uses only eight guqin melodies to create corresponding se tablatures, and most of these are relatively simple pieces. Notably, in transcribing the piece

“Dongting Qiu Si” (Autumn Thoughts at Dongting), which in the original qin version uses a fixed tuning with no string retuning — he modifies the qin version to use strings 1, 3, and 6, and at the same time requires lowering the se bridge. Similarly, when playing

“Saishang Hong" (Wild Geese Beyond the Frontier), he raises the yu string on the se by one pitch. This shows that his se tablature does not offer a comprehensive method for adapting to changes in qin tuning; hence, his work does not resolve the fundamental issue of coordinated tuning for qin and se ensemble performance. The situation is analogous to the qin-xiao] duet manuals (Qin Xiao He Pu), where the xiao ultimately cannot align with the qin, and the failure is blamed on the structure of the pieces themselves. It is a comparable frustration. till, Qingrui’s work is at least more honest and grounded than Zhou Xianzu’s Qin Xiao He Pu.

本编據清同治庚午(公元一八七O年)刻本影印。

This edition is reproduced from a woodblock-printed copy of the Tongzhi gengwu year (1870).

There are also other handbooks for qin and se together. For the content of this one see Appendix I below.

(Return

16.

Private Manual for Qin Studies at the Studio for Using the Six (Tones?) to Rectify the Five (Knowledges?) (以六正五之齋琴學秘書

Yi Liu Zheng Wu zhi Zhai Qinxue Mishu)

(Note that it is 五之齋 not 五知齋.) Zha Fuxi's Preface to this handbook says,

In the late Qing period, as traditional (feudal) culture declined, few who engaged in qin studies or qin performance pursued any kind of systematic research. As a result, among the qin craftsmen and instructors of the major cities — those who made their living by repairing and teaching qin — there only occasionally emerged figures who rose to prominence and gained widespread renown for a time, and who at times expressed themselves through written works. The Private Manual for Qin Studies at the Studio for Using the Six to Rectify the Five is a representative example.

孫寶,魏誉齋,又自號「長安市上彈無絃琴者」。他的父親是在外地作武官,因父死家貧,在光緒元年(公元一八七五年)五十六歲時寫了這一部琴譜。他在《韻罄琴序銘費》中說:

Sun Bao, style name Weiyuzhai, also referred to himself as “One who plays the stringless qin on the streets of Chang’an.” His father served as a military officer in a distant post. Following his father’s death, the family fell into poverty. In the first year of the Guangxu reign (1875), at the age of fifty-six, Sun compiled this qin manual. And in his "Preface and inscription to Yunqing Qin", he wrote:

"After I turned 20 my father passed away. Our official stipend was meager, and the household became increasingly strained. I had no particular pastimes in life, except a fondness for leisurely playing the qin. I came to understand somewhat of tone and mode, and to my surprise, nobles and ministers of the capital, gentlemen and officials, monks and Daoists, merchants, maidens — all came to study the qin.”

「於是教蒙童於家塾,賣琴卜于長安,閒暇之時,作有《以六正五之齋琴學秘譜》一部」。

"Thus I taught children at a family school, sold qins and practiced divination in Chang’an; and in my spare time compiled a work titled "Private Manual for Qin Studies at the Studio for Using the Six to Rectify the Five)".

書共六卷,都是他的後人鈔錄他譜。 (《與古齋》等的琴論局部有刊印)。唯卷六著琴曲二十一曲,内有其自

作《孤兒行》一曲。

The book comprises six folios, all transcribed by (Sun's) descendants. (Qin essays such as Yuguzhai were in part printed.) Only Folio six includes music: it contains twenty-one qin pieces, among them Sun Bao’s original composition “Ballad of the Orphan” (Gu’er xing).

此書清代刻本已很難見到。現中國藝術研究院圖書館藏有清刊殘本(卷二)。國家圖書館藏有民國十六年孫啟清刊傳纱本。本编除卷二用原刊殘本外,其餘卷首、卷五(部分)及卷六曲譜均用民族音樂研究所據傳鈔本重錄之本影。

Printed editions from the Qing dynasty are now extremely rare. The Library of the Chinese National Academy of Arts holds a fragmentary Qing-printed copy (Folio two). The National Library of China holds a thread-bound silk-facsimile edition printed by Sun Qiqing in the 16th year of the Republic (1927). For the current edition, Folio two is based on the surviving printed fragment, while the prefaces, parts of Folio 5, and all musical scores in Folio six have been reproduced from manuscript copies preserved at the Institute of Ethnomusicology.

Appendix II below lists its content.

(Return)

Handbook of the Rong Family Tradition

(香江容氏琴譜 Xiangjiang Rongshi Qinpu)

| Book cover (see inside) |

In 2015 容克智 Hammond Yong published this handbook, which has

three folios in traditional binding plus an audio DVD. The full title would be better translated as "Qin Handbook from the Rong Family of the Pearl River Estuary". Related terms are "容氏家族琴學傳承 Rongshi Jiazu Qinxue Chuancheng" (Rong Family Tradition of Qin Study) or simply "容氏家族琴学 Rongshi Jiazu Qinxue" (Rong Family Qin Study).

In 2015 容克智 Hammond Yong published this handbook, which has

three folios in traditional binding plus an audio DVD. The full title would be better translated as "Qin Handbook from the Rong Family of the Pearl River Estuary". Related terms are "容氏家族琴學傳承 Rongshi Jiazu Qinxue Chuancheng" (Rong Family Tradition of Qin Study) or simply "容氏家族琴学 Rongshi Jiazu Qinxue" (Rong Family Qin Study).

Note the use of 香江 Xiang Jiang ("香江 Fragrant River") rather than 香港 Xiang Gang (Fragrant Harbor, the standard term for Hong Kong). In Cantonese the two terms are pronounced almost the same, and some people believe Xiang Jiang to be the original name for what is now called Hong Kong. Whatever is origins, as used here it is intended evoke the connection between 香江 Hong Kong and the 珠江 Pearl River, which comes down to Hong Kong and Macau through Guangzhou (Canton). Recently this term has acquired some currency, but since 2017 the official term for this region has become 粵港澳大灣區 Yue Gang Ao Dawan Qu (Yuè Gǎng Ào Dàwān Qū; Jyut6 Gong2 Ou3 Daai6 Waan1 Keoi1): Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area.

In addition to a number of essays this handbook includes tablature for 33 melodies taught from this lineage (below; no transcriptions). Some of them come from old family scores going back to Qing Rui himself; others can be found in handbooks such as those mentioned in Appendices I and II. The enclosed DVD has recordings of 19 of the 33 tablatured melodies on 34 tracks (15 of the melodies are each recorded first by Yong Sze-chak then by Hammond himself ("Yong Hak-chi"), making 30 tracks in all; on the remaining four tracks Hammond plays three pieces [tracks 1, 21 & 26] and his father one [track 12]). The recordings by Yong Sze-chak, made between 1986 and 1995, all use metal strings. Hammond's recordings were all made in 2014 using silk strings, to which he had recently returned.

Tablature and Recordings in

香江容氏琴譜 Xiangjiang Rongshi Qinpu (Hong Kong 2015)

With indication of tracks on the accompanying DVD

(YSC = 容思澤 Yong Sze-chak;

YHC = 容克智 Yong Hak-chi; none = no recording)

| # | title | romanized | CD track | page in handbook; further comments |

| 1. | 猗蘭 | Yi Lan | 1. YHC | p.15: "李成宇先生授 given by teacher Li Chengyu";

also first piece in 1836 but 1836 pu is somewhat different |

| 2. | 瀟湘水雲 | Xiao Xiang Shui Yun | 2. YSC

3. YHC | p.19: "李成宇先生授 given by teacher Li Chengyu";

47th piece in 1836; 1836 pu also different |

| 3. | 釋談章 | Shitan Zhang | 4. YSC (10.54)

5. YHC (12.24) | p.24: "韓子十耕原搞 originally copied out by Master Han Shigeng"

not in 1836; related to 1722a; no lyrics |

| 4. | 塞上鴻 | Saishang Hong | 6. YSC

7. YHC | p.29: "李成宇先生授譜 tablature given by teacher Li Chengyu" |

| 5. | 梧葉舞秋風 | Wu Ye Wu Qiu Feng | 8. YSC

9. YHC | p.34: "李成宇先生授譜 tablature given by teacher Li Chengyu" |

| 6. | 鷗鷺忘機 | Oulu Wang Ji | none

| p.37: ”參訂古譜 examined old tablature" but same (though adding comments) as 1836 pu, which says "from Gugang Yipu". Also very similar to 1677. |

| 7. | 雁落平沙 | Yan Luo Ping Sha | 10. YSC

11. YHC | p.39: "李成宇先生授譜 tablature given by teacher Li Chengyu" |

| 8. | 搗衣 | Dao Yi | 12. YSC | p.42; 1836 pu somewhat different |

| 9. | 水仙 | Shui Xian | 13. YSC

14. YHC | p.47: "趙孟梅道兄授孟";

1836 pu is same. |

| 10. | 汜橋進履 | Si Qiao Jin Lü | 15. YSC

16. YHC | p.52: "孫西耘道兄授譜 tablature given by (Qing Rui's) friend Sun Xiyun"; title and music as in 1836 but afterword is different. Usually called 圯橋進履 Yiqiao Jin Lü; 汜 si = (name of ?) stream. |

| 11. | 漁樵問答 | Yu Qiao Wenda | 17. YSC

18. YHC | p.55; starts same as 1836 pu but then diff. |

| 12. | 良宵引 | Liang Xiao Yin | 19. YSC

20. YHC | p.58; not in 1836 |

| 13. | 梅花三弄 | Meihua Sannong | 21. YHC | p.59: "參訂古譜 examined old tablature"; not same as 1836 |

| 14. | 玉樹臨風 | Yu Shu Lin Feng | 22. YSC

23. YHC | p.63: "參訂古譜 examined old tablature", but same as 1836, which says "from Gugang Yipu". Actually almost same as 1677. |

| 15. | 碧澗流泉 | Bijian Liu Quan | 24. YSC

25. YHC | p.65: "古岡遺譜 Gugang Yipu"; 1836 pu same. |

| 16. | 雙鶴聽泉 | Shuang He Ting Quan | None | p.68: "參訂古譜 examined old tablature", but same as 1836, which says "from Gugang Yipu". |

| 17. | 風雷引 | Feng Lei Yin | None | p.70 |

| 18. | 神化引 | Shenhua Yin | None | p.74: "參訂古譜 examined old tablature", but same as 1836 (adding comments), which says "from Gugang Yipu". |

| 19. | 懷古 | Huai Gu | None | p.77: "古岡遺譜 Gugang Yipu"; 1836. |

| 20. | 洞庭秋思 | Dongting Qiu Si | 26. YHC | p.79 |

| 21. | 春曉吟 | Chun Xiao Yin | 27. YSC

28. YHC | p.81 |

| 22. | 挾仙遊 | Xie Xian You | None | p.83; 11+1 sections; seems same as 1836 (XXII/396) |

| 23. | 清夜聞鐘 | Qing Ye Wen Zhong | None | p.86 |

| 24. | 漁歌 | Yu Ge | None | p.92 |

| 25. | 搔首問天 | Sao Shou Wen Tian | 29. YSC

30. YHC | p.99; pu seems same as 1836 (recording by Yong Sze-chak also on BiliBili) |

| 26. | 樵歌 | Qiao Ge | None | p.103 |

| 27. | 岳陽三醉 | Yueyang San Zui | None | p.108: "武林李氏訂 fixed by Mr. Li of Wulin" |

| 28. | 碧天秋思 | Bi Tian Qiu Si | None | p.114: no source given for #24-#33 |

| 29. | 關雎 | Guan Ju | None | p.117 |

| 30. | 山居吟 | Shan Ju Yin | None | p.121 |

| 31. | 墨子悲絲 | Mozi Bei Si | None | p.124 |

| 32. | 雁度衡陽 | Yan Du Hengyang | 31. YSC

32. YHC | p.129 |

| 33. | 白雪 | Bai Xue | 33. YSC

34. YHC | p.134 |

| pp.137-173 (end): essays and charts |

(Return)

|

Appendix I: Table of Contents for

琴瑟合譜 Qinse Hepu (QQJC XXVI 115-187; 1870) See also Zha Fuxi's preface above |

| Opening pages of Qinse Hepu |

Qing Rui published this "Handbook for Playing Qin and Se Together" as part of an effort to encourage a revival of the se through arranging qin melodies so that they could also be played on se.

Qing Rui published this "Handbook for Playing Qin and Se Together" as part of an effort to encourage a revival of the se through arranging qin melodies so that they could also be played on se.

The image to the right shows (XXVI/116):

- Top right is the title page.

- Top left is the next page, showing text with four images in two rows:

- The row in the middle has a large diagram of the bottom of a se with its singular sound hole and the strings as extended from the lower end of the se top; the text to its right does not make clear how they are fastened to the se.

- Left row top to bottom are a tray apparently to hold strings, one of the moveable bridges and one of the two frames one which the se rests.

- A diagram showing how to place the qin and se so that each player is facing the other.

After this is,

- Preface by the author then two others (XXVI/117)

- 目錄 Table of Contents (XXVI/123)

- 凡例 Outline (XXVI/123)

- 瑟中五音制字定位 On a se, for the five tones how to indicate finger placement (linked with explanation above; XXVI/128)

- 鼓瑟左手指法 Left hand techniques for playing se (linked with explanation above (XXVI/128)

- 鼓瑟右手指法 Right hand techniques for playing se (linked with explanation above (XXVI/128-9)

- 彈琴右手指法 Left hand techniques for playing qin (XXVI/129)

- 彈琴左手指法 Right hand techniques for playing qin (XXVI/131)

- 附:五知齋琴譜例論 Attached: Essays from Wuzhizhai Qinpu (XXVI/135)

- 琴瑟譜 Tablature for thirteen melodies for qin and se together (XXVI/150-187)

| Tablature in Qing Rui's Qinse Hepu |

The tablature in the image at right is for Liangxiao Yin

(compare this transcription), the first melody in the handbook. Its preface mentions Qing Rui, his concubine Li Zhixian and a friend. As for the music itself, the first line has the se part, the second line is the corresponding qin melody. Both begin in harmonics, but it is not clear what "harmonics" is meant when playing the se. The ornament in the se part apparently has to do with left hand vibrato to the left of the moveable bridge.

As explained above, including the image, at the top of each cluster are the symbols 𠂊山刀宀口, corresponding to the relative pitches 12356. And where one expects string numbers there is only numbers from 1 to 3 (一二三, occasionally 四, very rarely 五): this seems to indicate the register (octave), so presumably it is left up to the player which string to pluck/strike.

The tablature in the image at right is for Liangxiao Yin

(compare this transcription), the first melody in the handbook. Its preface mentions Qing Rui, his concubine Li Zhixian and a friend. As for the music itself, the first line has the se part, the second line is the corresponding qin melody. Both begin in harmonics, but it is not clear what "harmonics" is meant when playing the se. The ornament in the se part apparently has to do with left hand vibrato to the left of the moveable bridge.

As explained above, including the image, at the top of each cluster are the symbols 𠂊山刀宀口, corresponding to the relative pitches 12356. And where one expects string numbers there is only numbers from 1 to 3 (一二三, occasionally 四, very rarely 五): this seems to indicate the register (octave), so presumably it is left up to the player which string to pluck/strike.

In all, the handbook includes the following eight qin melodies, each aligned with an arrangement for se zither:

- Liangxiao Yin (XXVI/150)

A few differences from 1875 #14 - Yu Qiao Wenda (XXVI/152)

More differences from 1875 #7 - Yan Luo Pingsha (XXVI/157)

Numerous differences from 1875 #18 - Wu Ye Wu Qiu Feng (XXVI/160)

Differences from 1875 #9 - Chun Xiao Yin (XXVI/164)

Not in 1875 - Dongting Qiu Si (XXVI/167)

Not in 1875 - Shitang Zhang (XXVI/170)

Hammond Yong's YouTube rendition is from here (comment); quite similar to 1875 #16 - Saishang Hong (XXVI/179-183)

Hammond Yong's YouTube recording is from here; quite a few differences from 1875 #10

|

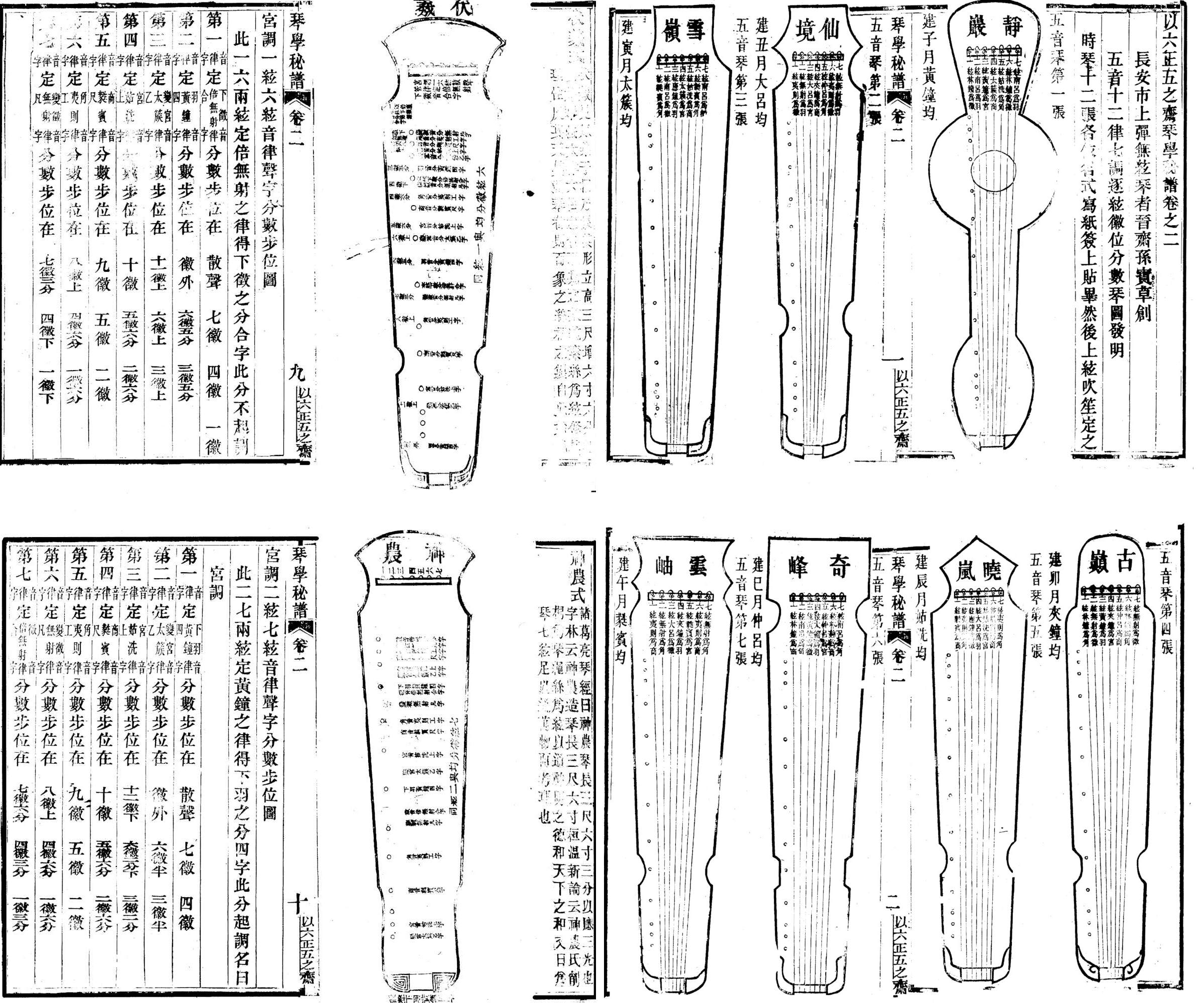

Appendix II: Table of Contents for

以六正五之齋琴學秘書 Yi Liu Zheng Wu zhi Zhai Qinxue Mishu 1875; XXVI/187-263 (tablature begins p.231) See Zha Fuxi Preface. |

| The 76 qin styles include: right page: first seven; left page 25th and 26th |

The front page (original cover?) says this handbook is "長安市上彈無絃琴者晉齋孫寶草創 a rough copy by Sun Bao, nicknamed Sun Jinzhai, player of a stringless qin in Chang'an Town". Sun, born in 1819, is said to have been a student of Qing Rui and Qing Rui's teacher Li Chengyu. See details in

the preface by Zha Fuxi.

The front page (original cover?) says this handbook is "長安市上彈無絃琴者晉齋孫寶草創 a rough copy by Sun Bao, nicknamed Sun Jinzhai, player of a stringless qin in Chang'an Town". Sun, born in 1819, is said to have been a student of Qing Rui and Qing Rui's teacher Li Chengyu. See details in

the preface by Zha Fuxi.

After this there is:

I. 自序 Self-Preface (XXVI/189-90)

II. Four folio pages with content I haven't figured out (XXVI/191-2)

III. Diagrams for 76 qin (XXVI/193-225)

Such depictions of qin styles go back to at least the Song dynasty. For details on these see these examples,

"styles" and

other lists. In this handbook all the qin are named but I do not completely understand all the details. To start with, the setup is not uniform all the way through. Thus, in the image at right, compare the text of the first seven (XXVI/193) with that of #25 (Fuxi) and #26 (Shen Nong; XXVI/197). In both cases the pitch of each string seems to be named, but then with the latter two a lot more information not found in such lists elsewhere.

IV. Qin tablature (XXVI/226-263)

First there is an essay ("孫晉齋韻罄琴序銘贊" 226-229, then there are 21 qin melodies in all. Six are the same titles as in Qinse Hepu, a handbook compiled by Qing Rui himself, but with mostly different versions of those melodies. The pages with tablature are all marked Private Tablature for Qin Study (琴學秘譜 Qin Xue Mi Pu). The title is clearly a reference to the early Guangling School handbook Wuzhizhai Qinpu (1722).

- Sheng Jing (Da Xue Zhangju; 4 sections; XXVI/231)

Confucian lyrics: the 大學 Da Xue - Mohebanruopoluomiduo Xinjing (1 section; XXVI/2)

Buddhist lyrics: the Heart Sutra; only here - Huangdi Yinfu Jing (7 sections; XXVI/233)

Daoist lyrics: the "黃帝陰符經 Yellow Emperor's Hidden Talisman Classic" (details); the lyrics begin, "觀天之道,執天之行盡矣...."); only here - Oulu Wang Ji (3+1 sections; XXVI/234)

Commentary with each section - Kai Gu (4+1 sections; XXVI/235)

Commentary with each section - Gao Shan (8+1 sections; XXVI/236)

Commentary with each section - Yu Qiao Wenda (7+1 sections; XXVI/238)

No commentary; compare version in Qinse Hepu - Qiu Sai Yin (9+1 sections; XXVI/239)

Foreword - Wuye Wu Qiufeng (8+1; XXVI/241)

Afterword; compare version in Qinse Hepu - Saishang Hong (16+1; XXVI/242)

Foreword and afterword - Canghai Long Yin (7+1; XXVI/244)

Foreword - Yuhua Deng Xian (30+1; XXVI/246)

Zha Guide; preface attributes it to Wulingxianzi - Qiujiang Yebo (3; XXVI/250)

Compare Yin De in chart - Liangxiao Yin (3; XXVI/251)

Afterword; compare version in Qinse Hepu - Gengxin Diao Wei (1 section; XXVI/251)

Only here; no commentary other than "清徵調宮音 qingzhi diao, gong yin" (mode) - Shitan Zhang (XXVI/252)

See in chart; compare version in Qinse Hepu - Feng Xiang Xiao Han (1; XXVI/254)

Short song - Pingsha Luo Yan (7+1; XXVI/255)

See in chart; compare version in Qinse Hepu - Qiao Ge (11; XXVI/256)

Copies preface, lyrics and music from 1589 - Gu Er Xing (5; XXVI/259)

Only here; "長安市上彈無絃琴者孫晉齋譜 tablature of Sun Jinzhai"; lyrics - Zui Yu Chang Wan (12; XXVI/261)

See in chart; foreword and afterword

At the end there seems to be a 12-line afterword by Wang Shixiang that sums up details about the book and mentions 汪孟舒 Wang Mengshu.

Return to QSCB,

or to the Guqin ToC.