|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Handbook List Zha Preface related: Taiyin Daquanji | 聽錄音 Recordings: 黃鶯吟 Golden Oriole / 調意 modal preludes 首頁 |

|

Shilin Guangji

1

A Comprehensive Record of Affairs, compiled by Chen Yuanjing2 |

事林廣記

1269 |

|

An annotated translation; the general introduction is with footnotes

below:

Nine pages in the original; copied here from QQJC I/17-22) |

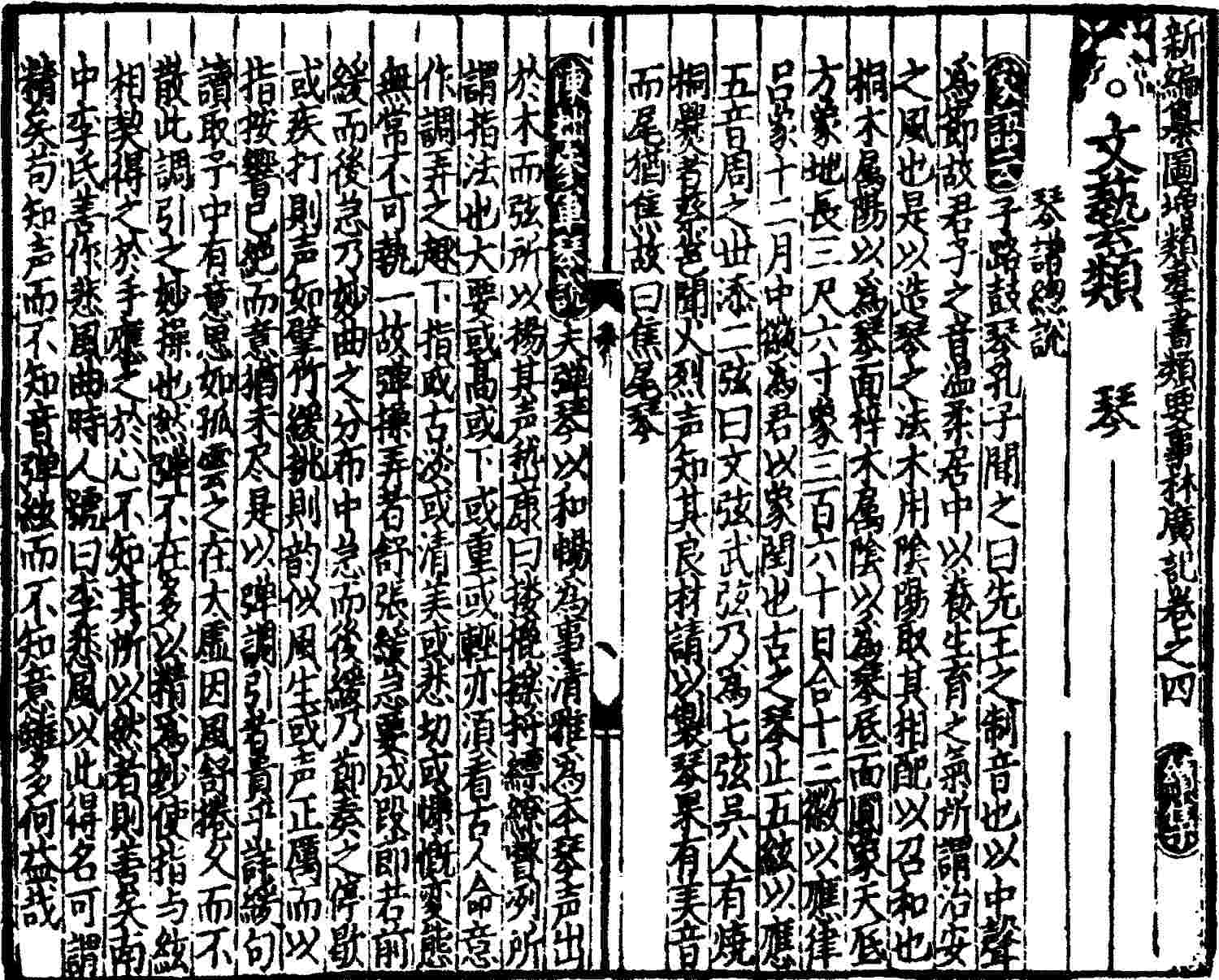

p. 1 of Shilin Guangji QQJC

I/17a (top):

Titles and two introductory essays |

The first column in the image at right, says,

"新編纂圖增類書類要事林廣記卷之四"(續集)

Newly Compiled, Illustrated and Expanded Shilin Guangji, Folio 4 (continuation).3

The second column (in large type) says,

The third column says:

There are then two essays (compare this with Taiyin Daquanji, Folio 5, Part 1).

When Zilu was playing the qin Confucius heard him and said, When the rulers of antiquity created sounds they relied on balanced tones to moderate them, thus a gentleman's sounds are temperate. While living flexibily, using a nurturing and fostering attitude, this is what is called an aura of providing peace.

(The rest of the Jia Yu passage, as follows, was omitted from

the version in Taiyin Daquanji

"文藝類 琴"

Literature and Arts Category (of the Shilin Guangji), Qin section

琴譜總說 General comments on Qin-related material

5

.)

是以造琴之法。木用陰陽,取其相配,以召和也。桐木屬陽以為琴面,

梓木屬陰以為琴底。面圓象天,底方象地。長三尺六寸象三百六十日合。十三徽以應律呂象十二月,中徽為君,以象閏也。古之琴止五絃以應五音。周之世添二弦,曰文弦、武弦,乃為七絃。吳人有燒桐爨者:蔡邕聞火烈聲,知其良材,請以製琴。果有美音而尾猶焦。故曰「焦尾琴」。

This is the method of making qin.

Use wood based on yin and yang, selecting it based on how (the pieces) complement each other, so that they provide harmony. Tong wood is yang so it should be used for the top board; zi is yin so it should be used for the bottom board. The top is round, like the sky, the bottom is flat, like the earth. The length is 3 chi and 6 cun, like the 360 days days (of the year). The 13 harmonic markers (hui) correspond to the (12) music tones and 12 months, with the middle marker as the master, much like an intercalary month. Of old the Qin had only five strings to correspond with the five tones.

The Zhou period added two strings, called the wen string and the wu string, thus making seven strings. As some people of Wu were burning wood for cooking,

Cai Yong heard the sound of fire crackling and knew (the wood) was good material, so he asked if he could use it to make a qin. The result was that had a beautiful sound though the tail was scorched. As a result it was called the "Scorched Tail Qin".

嵇康

(琴賦)曰﹕

「摟、批、擽、捋、縹、繚、潎、洌,(或是:「摟批、擽捋、縹繚、潎洌,)」所謂指法也。大要或高或下,或輕或重,亦湏看古人命,意作調弄之趣,下指或古淡、或清美、或悲切、或慷慨,変態無常,不可執一。故彈操弄者,舒張緩急。要成段節,若前緩而後急,乃妙曲之分佈。中急而後緩,乃節奏之停歇。或疾打則聲如擘竹。

緩挑則韻似風生。或聲正厲而以指按,響巳絕而意猶未儘。是以彈調引者,貴乎詳緩句讀,取子中有意思。

如孤雲之在太虛。因風舒捲,久而不散。此調引之妙操也。然彈不在多,以精為妙,使指與絃相契,得之於手,應之於心。不知其所以然者則善矣。

*

南中李氏善作悲風曲時人號曰李悲風以此得名可謂精矣苟知聲而不知音彈絃而不知意雖多何益哉。

緩挑則韻似風生,或聲正厲而以指按,響巳絕而意猶未儘,是以彈調引者。貴乎詳緩句讀,取子中有意思。

如孤雲之在太虛。因風舒捲,久而不散。此調引之妙操也。然彈不在多,以精為妙,使指與絃相契,得之於手,應之於心。不知其所以然者則善矣。若夫天性聰明,取聲奇異,性出於聲,聲出於心,此殆神妙又不可論此也。苟知聲而不知音,彈絃而不知意,雖多何益哉。

(Military District Administrator Chen Zhuo in his Qin Talk said),

"To play the qin is to prioritize fluent harmony with elegance at the foundation. Qin sounds come out from wood with strings used to amplify the sound.

(Xi Kang wrote that), "Lōu, pī, luò, lüè; piāo, liáo, piē, liè are all fingering techniques."

Essential facets such as playing high or low, light or heavy, you have to consider what the ancients called for. If intending to bring out the beauty of a melody then with your fingers you should be ancient and plain, pure and beautiful, sorrowful with poignancy and impassioned with resolution - constantly changing and never rigid.

So when people play melodies they use expansion and contraction, tempo changes, and phrasing that forms distinct sections. If a passage starts slowly and then accelerates, this is a distinction of a well-made piece. If it begins rapidly and then slows, this creates a natural rhythmic pause. A forceful strike can make the sound like splitting bamboo.

A gentle pluck produces a resonance like the movement of wind. Sometimes, a note is played forcefully, yet through finger pressure, its resonance extends even after the audible sound has ceased.

Therefore, in playing melodic preludes (diaoyin), careful attention should be given to detailed phrasing and pacing, extracting meaning from within the notes.

Like a solitary cloud drifting in the vast sky, it expands and contracts with the wind, lingering without dispersing. This is the essence of a sublime prelude.

However, playing should focus on precision rather than quantity. Mastery lies in the perfect coordination between fingers and strings, where the hands execute effortlessly and the heart resonates with the music. The highest level of skill is when one plays without consciously knowing how — it simply happens naturally.

As for those with innate talent, who produce extraordinary sounds, their nature manifests through music, and their sound arises from the depths of the heart — this reaches the realm of the divine and cannot be easily discussed.

But if one merely knows sound without understanding music, or plucks the strings without grasping their meaning, then no matter how much one plays, what benefit is there?

In the south a Mr. Li skillfully created (a piece called) Sorrowful Wind, so people of his time called him "Li Beifeng," naming him after his most famous piece. This is the mark of true mastery. Thus if one knows sound but not music, plucks the strings but does not grasp the intent — what use is playing so much?"

The Fire Emperor (Yan Di created the five string qin. The Xin Lun of Huan Tan said, Shen Nong (i.e., Yan Di) was the first to cut wood to make a qin. It also says, (or "it is also said") Wen Wang and Wu Wang of Zhou each added a string. The Li Yi Zuan said Yao caused

Mugou to make a five-string qin. The

Li Ji says,

Shun made a qin with five strings in order to sing Southern Breezes.

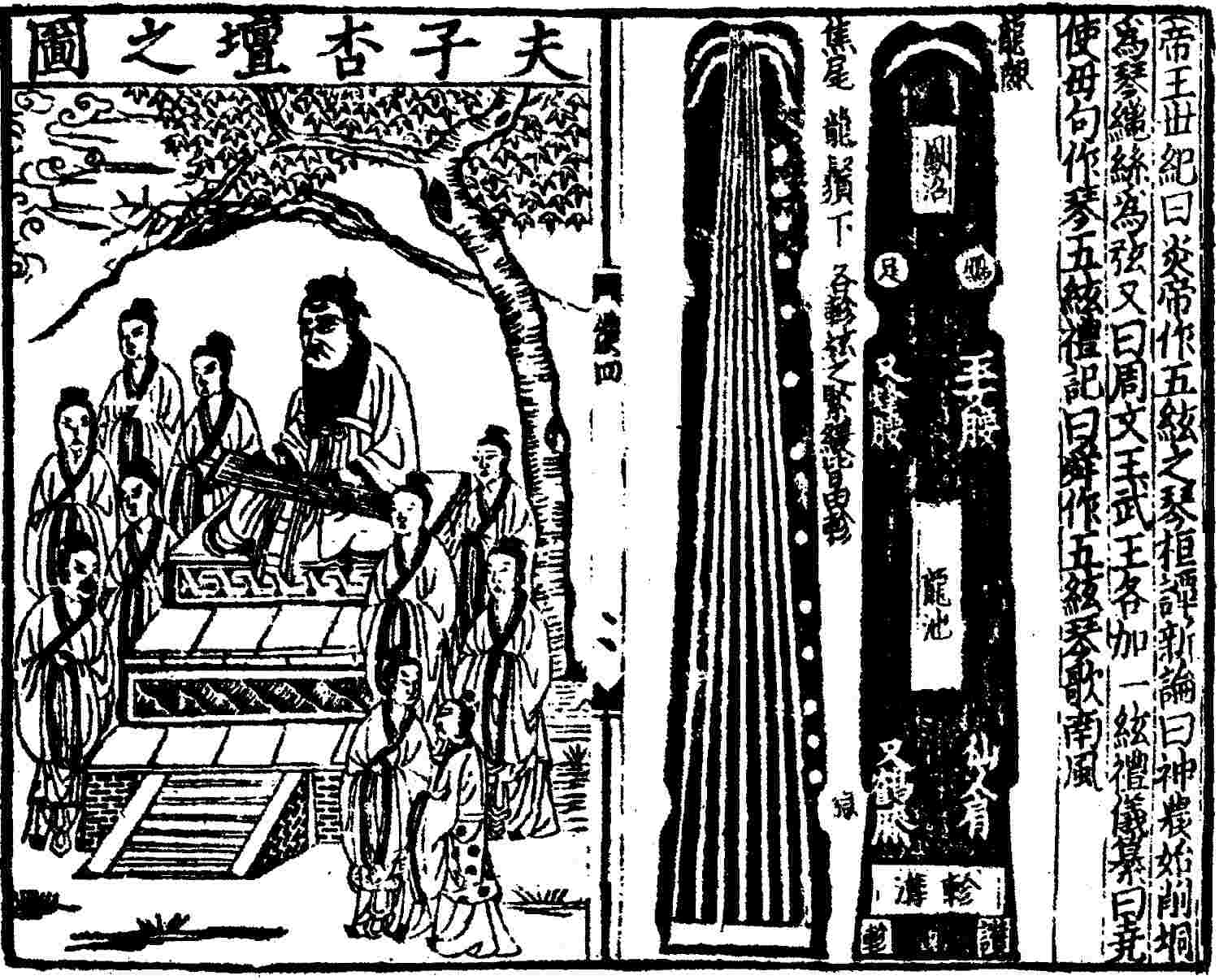

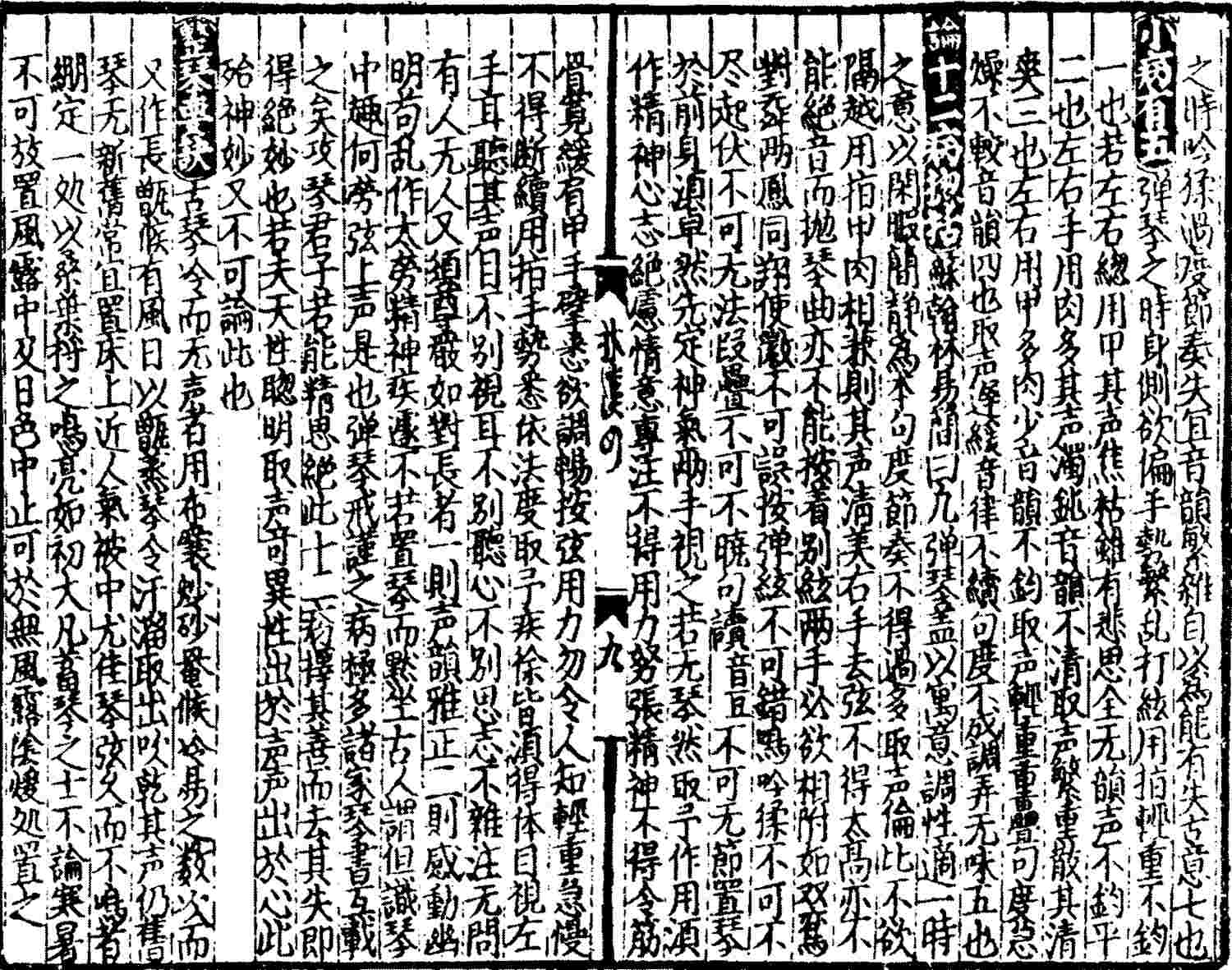

After those three lines the rest of the page as copied in QQJC I/17b has these two illustrations:

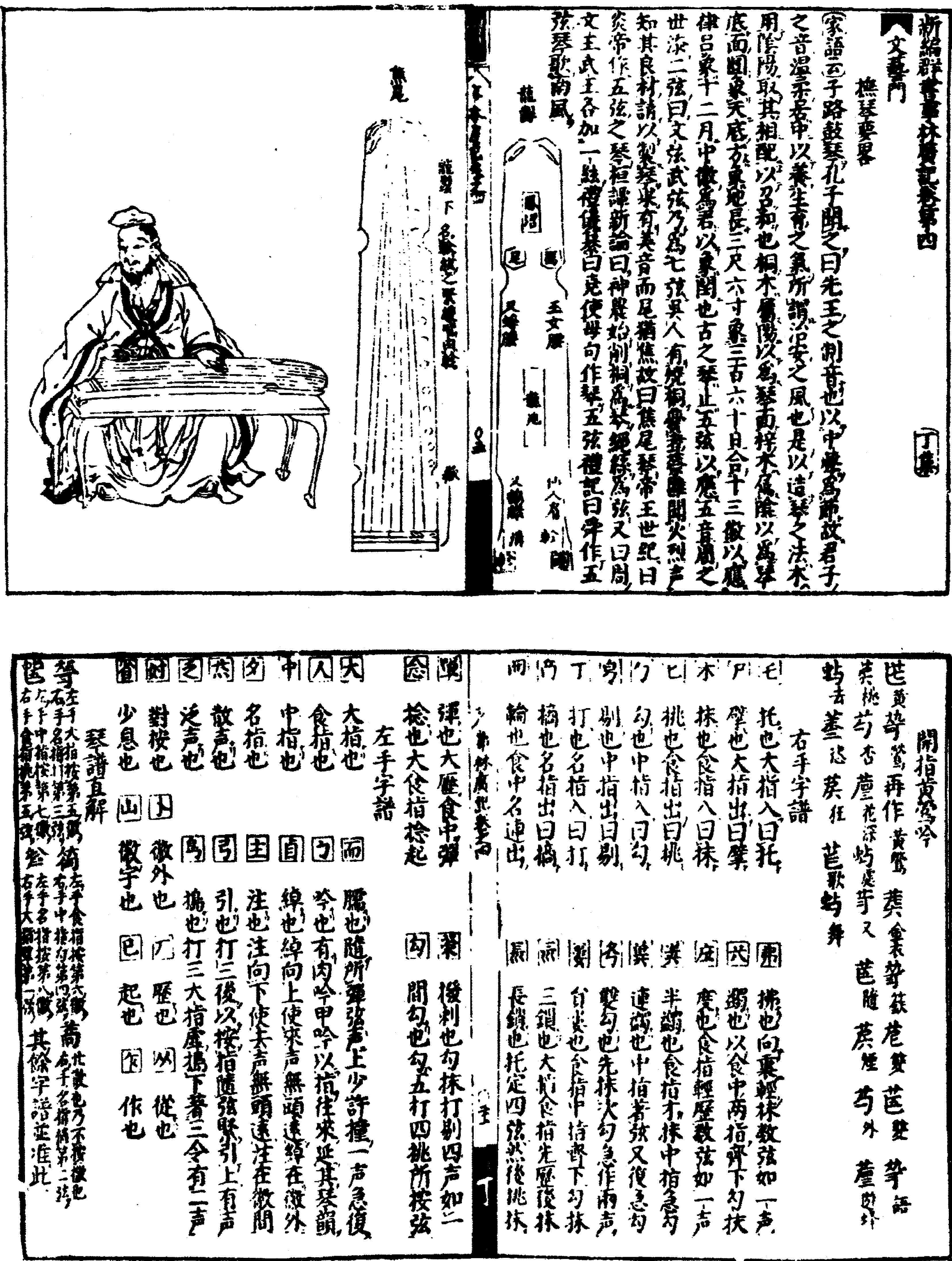

Many pages on this site have instructions such as these, but they are often difficult to organize and translate even in the few cases where the shorthand forms can be written on a computer.

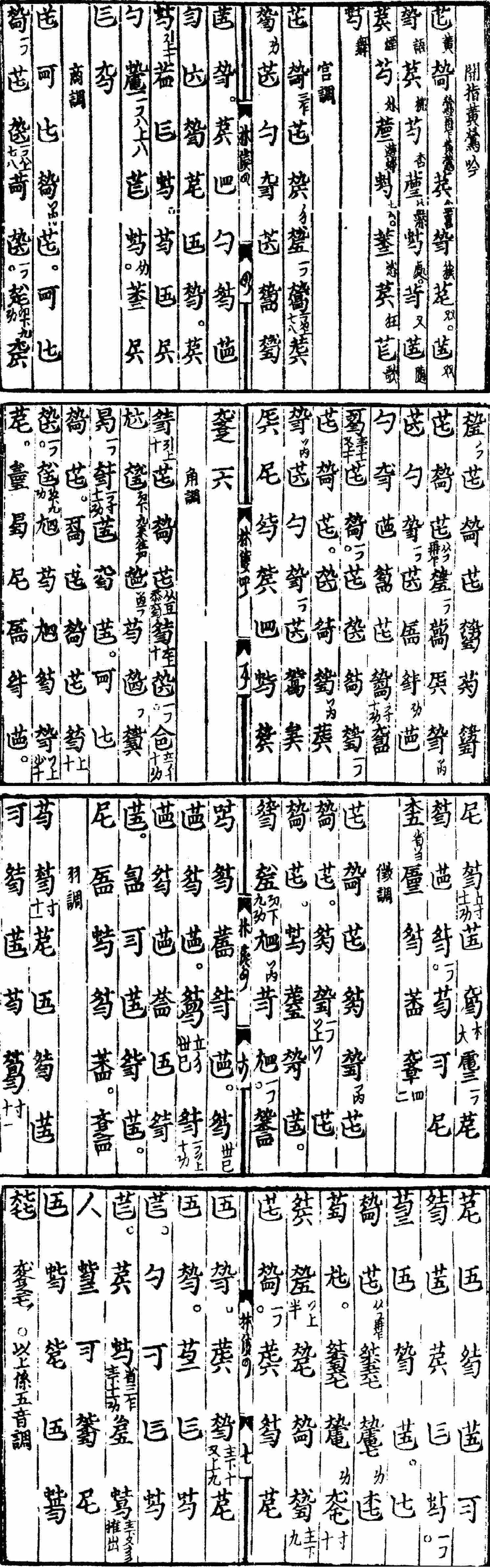

Page 4 (and 5-7) of Shilin Guangji: Tablature for the qin melodies12

Music and lyrics for Huang Ying Yin

13

(see my transcription; listen to my recording) (QQJC I/18)

雙雙語,桃杏益深處。

又隨煙外遊蜂去,

恣狂歌舞。

Listen above.

Golden Oriole is followed by the five modal preludes:

Commentary on the music:

Golden Oriole and the Five Modal Preludes

Tablature for Golden Oriole only survives from the present handbook, and the five modal preludes here are all quite different from those included in any other handbooks, including the other surviving Song dynasty collection, the five modal preludes found in the Qin tablature section of Taiyin Daquanji. All six melodies are short, especially Golden Oriole and there are recordings for all linked below,

'The swallow harmonises with the oriole' is a form of love-play, for which another metaphor is 'The oriole is randy and the butterfly plucks.' A 'floating oriole' (the Chinese word liu-ying suggests rather 'wandering oriole') is a prostitute: prostitutes were often singing girls into the bargain. A 'wild oriole' is a free-lance prostitute, i.e., non-registered. An 'oriole swallow' is a bar-maid, and 'oriole-flower-halls' are top-rank brothels.

The present melody survives only in Shilin Guangji (Zha Guide 1/---/4). Xu Jian discusses it briefly in QSCB, Chapter 6b1-8 (p.109), saying it "makes use of the song and dance of yellow orioles amongst flowering shrubs in order to express welcoming spring." "Song and dance" comes from the last line of the poem, perhaps suggesting it could have been a prelude to a melody for song and dance; if so, this would be very unusual for a qin melody.

Kaizhi are thought (there seems to be no available specific information on this) to have been preludes to specific melodies, in this way contrasting to diao yi, which more generally introduced modes (though some surviving ones seem to be attached to specific pieces). However, because none of the old qin melody lists includes a melody called Golden Oriole, it cannot be argued very strongly that this kaizhi was created for a specific melody.

As for Intonation of the Golden Oriole, intonations (吟 yin) are themselves often short melodies (see a list). And "Golden Oriole" itself seems to have been found in various artistic forms (I have not found any dance references). As for references:

48904.1347 also does not include the following, also said to be 黃峨(黃秀眉)的散曲黃鶯兒 Huang Ying'er. It is a sanqu written by Huang E (Huang Xiumei, 1498-1569; Wiki) to her husband.

The translation in

The Red Brush, p.290, begins, "The ceaseless rain brews up a light chill...." As for its form (5; 3,3; 7; 4,4; 7; 5), it does not seem to be related to that of the lyrics of the existing qin melody, but it is also unrelated to poems

included in Baidu to illustrate the structure of the cipai of this name.

There is also a poem almost exactly in the form of Huang E's included in the novel Jin Ping Mei (q.v.), as follows:

Translated in Roy, III/187-8.

These sanqu melodies still do not neatly fit with the surviving qin melody. However, they are closer in length than is the cipai. If the surviving melody can indeed be made to fit the longer lyrics what significance would that have? Could such creative explansion be considered as a valuable new creation based on Chinese tradition?

(Elsewhere the above passage may be

somewhat different.)

Page 2:

Qin diagram / Confucius at

Xing Tan

It names parts of the qin including

龍齦 longyin,

鳳沼 fengzhao,

鴈足 yanzu,

玉女腰 又蜂腰 yunü & fengyao,

龍池 longchi,

仙人肩又鶴膝 xianren jian & hexi,

軫溝 zhen'gou,

讚軫 zanzhen,

焦尾 jiaowei,

龍鬚下 longxu xia and

各軫絃之緊湲皆由軫 (?)

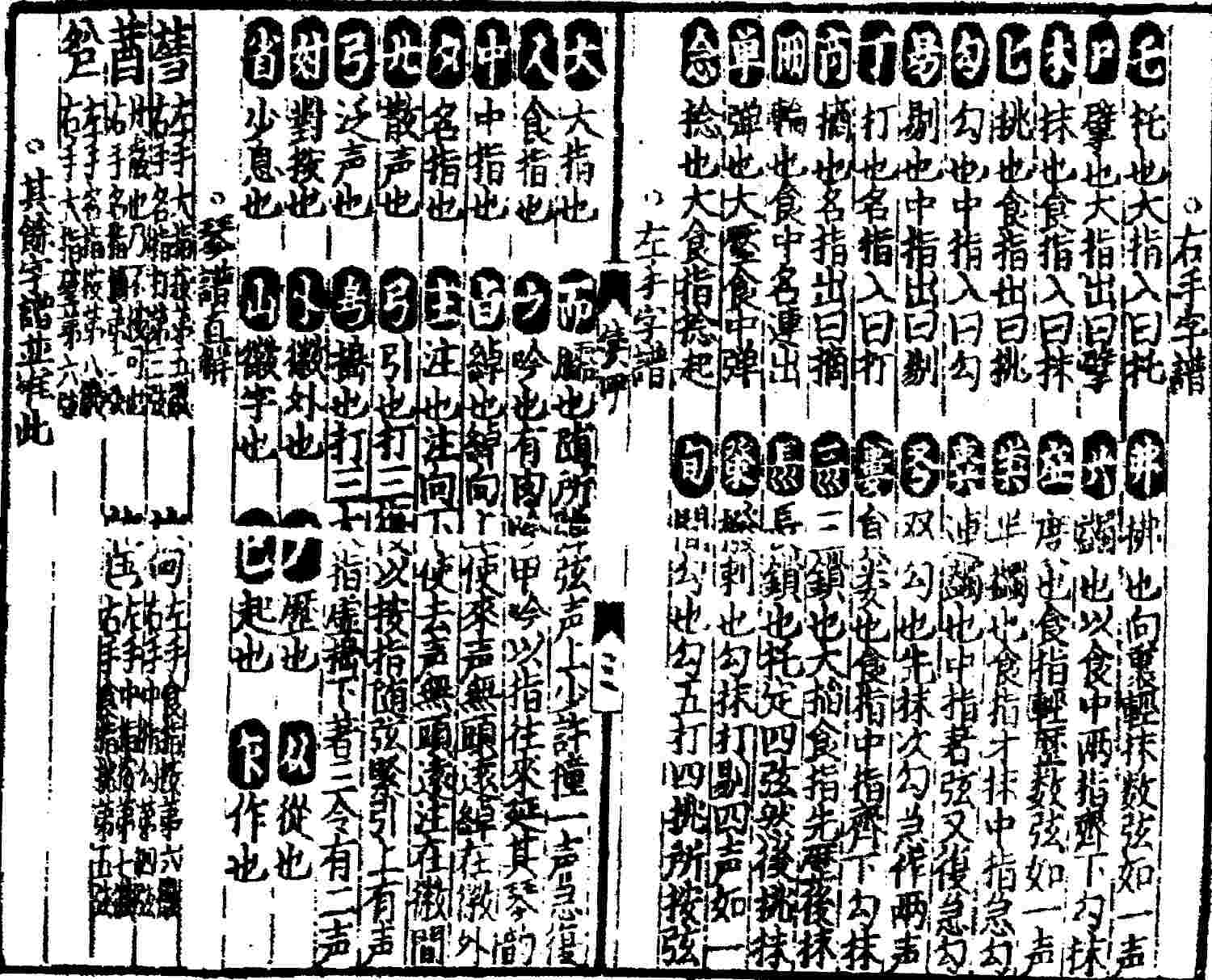

Page 3 of Shilin Guangji:

finger technique explanations, as follows:11 (I/18)

(see upper half of image from QQJC I/18 at right)

pp. 3 & 4 of Shilin Guangji, QQJC

I/18 :

above: finger techiques; below: qin tablature

22 entries beginning:

乇:托也 tuo; also

here: right thumb "supports" a string inwards

尸:擘也 pi; also

here: right thumb "cleaves" a string outwards

Old tablature explanations were inconsistent as to which of these two was inwards and which outwards.

木:抹也 mo; also

here: right forefinger "rubs" inwards

乚:挑也 tiao; also

here: right forefinger "pokes" outwards

....

20 entries beginning:

大:大指也 symbol for thumb ("big" finger)

人:食指也 symbol for index finger ("food" finger)

中:中職也 symbol for "middle" finger

夕:名指也 symbol for ring finger ("star" short for 名 "name" in "無名指"")

艹:散聲也 short for "scattered" sound: use open string

弓:泛聲也 (mistake? It says "harmonic" sound, but that is written differently)

....

Five examples intended to explain how the techniques are put together in clusters. There are printing errors in all five clusters, underlining the difficulty interpreting the ensuing tablature.

Tablature for all the melodies in Shilin Guangji

(commentary below)

Shilin Guangji pp.4-7 (QQJC

I/18b-20a)

(Shilin Guangji has one 開指 kaizhi and five 調意 diaoyi)

(see the lower half of image from QQJC I/18 at right)

The melody is short and simple, with its lyrics applied one character for each note:

Huáng yīng, huáng yīng, jīn xǐ cù.

Golden oriole, golden oriole, golden joy-filled clusters.

Shuāng shuāng yǔ, táo xìng yì shēn chù.

As a pair they converse; peaches and almonds grow abundent in all the recesses.

Yòu suí yān wàiyóu fēng qù,

And following beyond the mist where bees wander off,

Zì kuáng gē wǔ.

Wildly unrestrained we sing and dance.

, but on this see the comments under Lienü Yin.

The second half of this melody is quite similar to the latter half of the 1425 melody Zhao Yin. Perhaps this indicates that this Gong Diao was originally a prelude to Zhao Yin. Unlike the shorter Gong Yi in Taiyin Daquanji, Gong Diao has few phrases in common with the Shenpin Gong Yi of 1425. However, the modal characteristics are similar.

This melody is quite different from the Shang Yi in Taiyin Daquanji, as well as the

Shenpin Shang Yi of 1425. However, it shares with them similar modal characteristics, in particular the inclusion of both standard mi with flatted mi.

This melody is very similar to the second half of the melody Lienü Yin, suggesting that it perhaps was originally a prelude to that melody. Lienü Yin survives only in

Xilutang Qintong (1525), but this is perhaps evidence supporting suggestions that some or many of the melodies of Xilutang Qintong were copied from Song dynasty sources. Jue Diao seems unrelated to the modal preludes Jue Yi in

Taiyin Daquanji, and

Shenpin Jue Yi of 1425. Perhaps its modal characteristics are similar to those of Shenpin Jue Yi

As with the Zhi Yi in Taiyin Daquanji, the tuning here seems to be considered as 5 6 1 2 3 5 6. However, in Shenpin Zhi Yi, as well as Zhi Yi and the three zhi mode melodies of 1425, my interpretation is 1 2 4 5 61 2. For me the zhi mode has seemed the most complex. (For more on this see Modality in early Ming Qin tablature.) Thus, although all three preludes end on the open 4th string, or open 2nd and 4th together, the modal characteristics do not seem to me to be quite the same. As for the melody itself, it is also very different from those of these other two preludes.

This prelude has more notes than any other modal prelude published in 1425 or earlier. The modal characteristics are similar to those of the

Yu Yi in Taiyin Daquanji, and Shenpin Yu Yi of 1425, but otherwise the melodies seem unrelated.

These pages (4 to 7) contain the only tablature in this book. The full title of "Golden Oriole" is "開指黃鶯吟 Kaizhi Huang Ying Yin": "Opening Fingering Golden Oriole"; this marks it as a sort of melodic prelude. And although the titles of Section 4, Numbers 2 through 6 each gives only a mode name, clearly these are all modal preludes (diaoyi). Modal preludes generally served a group of melodies in that mode. This may be the only difference between them and kaizhi, which seem to have been preludes to specific melodies (as here with Golden Oriole). Unlike in Taiyin Daquanji, there are no lists here of melodies associated with the five diaoyi.

My transcription and recording are with the lyrics

above.

Of orioles Eberhard, A Dictionary of Chinese Symbols, p.221, writes,

Entry 48904.1347 does not give much detail about the cipai form; for this see, e.g., the examples to poems in this form

included in Baidu to illustrate the structure of the cipai of this name. Clearly the ci form called Huang Ying Er requires text much longer than that for the present short melody called 黃鶯吟 Huang Ying Yin.14

積雨釀輕寒。

看繁花 樹樹殘。

泥途滿眼登臨倦。

雲山幾盤,江流幾灣,

天涯極目空腸斷。

寄書難,無情徵雁,飛不到滇南。

書寄應哥前。

別來思,不待言。

滿門兒托賴都康健。 (+1 字 compared to previous)

舍字在邊,傍立著官,

有時一定求方便。

羨如椽,往來言疏,落筆起雲煙。

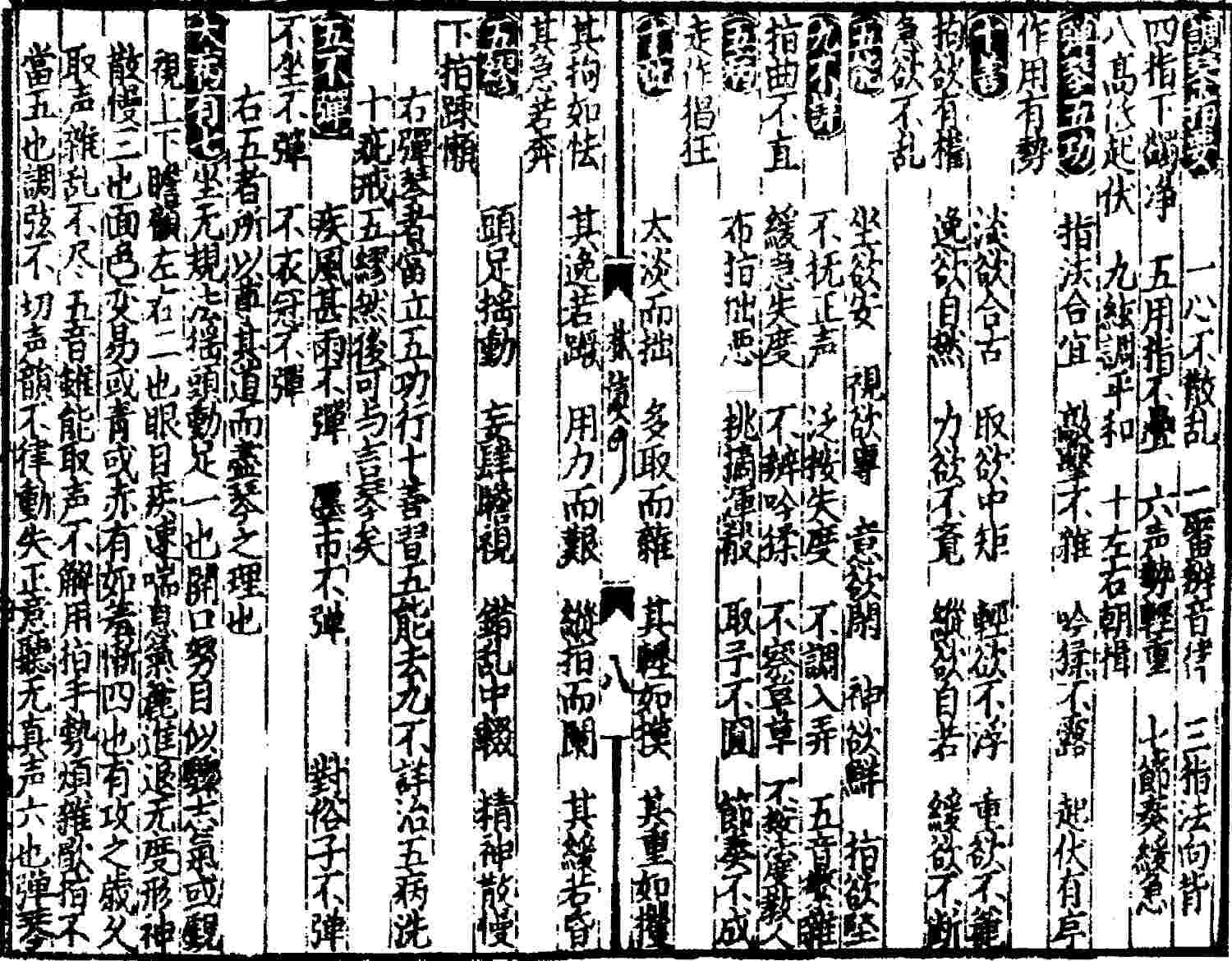

Details from pages 8 and 9 of Shilin Guangji

page 8 of Shilin Guangji, QQJC

I/20b

The two pages at right consist of 13 sets of guidelines for playing qin, the title of each section highlighted in black. The first twelve of these are in

Folio 6 of Taiyin Daquanji

The two pages at right consist of 13 sets of guidelines for playing qin, the title of each section highlighted in black. The first twelve of these are in

Folio 6 of Taiyin Daquanji

As for "Do's and don'ts of qin play" (彈琴宜忌 Tan Qin Yi Ji, it would seem that at the time I set up this page I got this title from somewhere, but at present I cannot recall who or what suggested it. (Online you can find this title along with the similar ones 鼓琴宜忌 and 學琴宜忌, but not within the context of these (or other) lists of rules; nor have I yet found any other overall title for such listings.

(彈琴宜忌 Do's and don'ts of qin play)

15

So, this is the name given here to what is perhaps the earliest known surviving version of a number of sets of rules about qin play (the various editions of Taiyin Daquanji claim items from the Song dynasty and earlier, but all surviving versions are later editions; likewise with other later handbooks claiming to have earlier such writings). Such rules were often included in qin handbooks (in particular from Taiyin Daquanji, which has an almost identical set as here but within a larger set. Perhaps biggest such collection of such sets of do's and don'ts (but not under or including that title) is in Qinshu Daquan Folio 10. All of these, however, are compilations.

What will be clear from the writings here on qin play is that the rules covered many different aspects, from demeanor and attitude to melody and execution. In this was the rules are rather different from some well-known later writings which seem to suggest that the most important aspect of the music itself is not melody but color. This argument will be outlined a bit more below.

Although the entries here under "do's and don'ts" were originally unnumbered, they have been numbered here for ease of of reference.

- 調琴指要 (Ten) Essentials of Qin Play}

(TYDQJ #11)

- 心不散亂 The mind must not be distracted.

- 審辨音律 Carefully distinguish pitch and intonation.

- 指法向背 Finger techniques should be properly aligned.

- 指下蠲凈 The fingers should show clarity and precision.

- 用指不疊 Do not use the fingering in a muddled way.

- 聲勢輕重 Balance the dynamics between light and heavy.

- 高低起伏 Highs and lows must flow naturally.

- 節奏緩急 The rhythm must balance the slow and fast.

- 絃調平和 Tune the strings into harmonious balance.

- 左右朝揖 The music should flow as though bowing left and right

- 彈琴五功 Five necessities of qin play

(TYDQJ #12)

- 指法合宜 Finger technique must be appropriate.

- 敲擊不雜 Plucking and striking must not be chaotic.

- 吟猱不露 Fast and slow vibrato must not be conspicuous.

- 起伏有序 The rise and fall must follow proper sequence.

- 作用有勢 Movements must convey momentum.

- 十善 Ten virtues

(TYDQJ #13)

- 淡欲合古 Simplicity should confirm with ancient standards.

- 取欲中矩 Execution must adhere to proper standards.

- 輕欲不浮 Lightness should not be superficial.

- 重欲不麄 Weightiness should not be coarse.

- 拘欲有權 Restraint must be exercised with balance.

- 逸欲自然 Free expression must remain natural.

- 力欲不斍 Strength should not be overbearing.

- 縱欲自若 Freedom must retain composure.

- 緩欲不斷 Slowness must not be disjointed.

- 急欲不亂 Speed must not be disorderly.

- 五能 Five capabilities

(TYDQJ #14)

- 坐欲安 When seated the posture should be steady.

- 視欲專 The gaze should be focused.

- 意欲閑 The mind should be calm.

- 神欲鮮 The spirit should be fresh.

- 指欲堅 The fingers should be firm.

- 九不詳 Nine negligences

(TYDQJ #15)

- 不撫正聲 Not playing the correct pitches.

- 泛按失度 Mismanaging harmonics and stopped notes.

- 不調入弄 Not tuning accurately before playing.

- 五音繁雜 Cluttering up the balance of the five tones.

- 指曲不直 Fingers not moving properly.

- 緩急失度 Mismanaging tempo variations.

- 不辨吟猱 Not distinguishing between different types of ornamentation.

- 不察草草 Playing carelessly without attention to detail.

- 不按法度教人 Teaching others without adhering to proper methods.

- 五病 Five deficiencies

- 布指拙惡 Finger placement being awkward .

- 挑摘渾殽 Inconsistent plucking techniques.

- 取予不圓 Uneven tone production.

- 節奏不成 Rhythm lacking coherence.

- 走作猖狂 Hand movements that are uncontrolled.

- 十疪 10 defects (the title suggests these are not quite as serious as the 病 dificiencies just listed)

- 太淡而拙 Too restrained, resulting in clumsiness.

- 多取而雜 Excessive variation, leading to disorder.

- 其輕如摸 A lightness touch as if merely brushing.

- 其重如攫 Heaviness as if clutching.

- 其拘如怯 Restraint as if timid.

- 其逸若蹶 Freedom that is more like stumbling.

- 用力而艱 Forcefulness that becomes labored.

- 縱指而闌 Overly relaxed fingering leading to carelessness.

- 其緩若昏 Slowness that suggests dullness.

- 其急若奔 Speed that suggests fleeing.

- 五繆 Five mistakes (easily identifiable actions)

- 頭足搖動 Head and feet move excessively while playing.

- 妄肆瞻視 Allowing the gaze to wander.

- 錯亂中輟 Pausing at inappropriate places.

- 精神散慢 Allowing the mind become unfocused.

- 下指疏懶 Finger movement that is careless and lazy.

(右彈琴者當立「五功」,行「十善」,習「五能」,去「九不詳」, 治「五病」,洗「十疵」,戒「五繆」,然後可與言琴矣。)

Thus, the qin player should establish the "Five necessities," practice the "Ten virtues," cultivate the "Five capabilities," eliminate the "Nine negligences," correct the "Five deficiencies," remove the "Ten defects," guard against the "Five mistakes," and only then can one speak of qin mastery.

(Why did this mention only #2 to #8?)- 五不彈 Five situations in which not to play

- 疾風甚雨不彈 When there is a fierce wind or heavy rain do not play.

- 廛市不彈 Marketplaces are no place to play.

- 對俗子不彈 When in front of vulgar people do not play.

- 不坐不彈 If not seated to not play.

- 不衣冠不彈 Without proper attire do not play .

右五者所以尊其道而盡琴之理也

(These five rules exist to uphold the dignity of the qin and fulfill its true principles.)- 大病有七 Seven great faults

- 坐無規法,搖頭動足,一也;

Sitting without proper posture, shaking the head and feet. - 開口努目,似驟志氣,或覷視上下,瞻顧左右二也;

Opening the mouth and widening the eyes as if startled, or darting glances up and down, looking around. - 眼目疾速,喘息氣麄,進退無度,形神散慢,三也;

Rapid eye movement, heavy breathing, moving without restraint, letting form and spirit become disordered. - 面色変易,或青或赤有如羞慚,四也;

Facial expressions changing excessively—turning pale or red, as if embarrassed. - 有攻之歲久,取聲雜亂,不盡五音,雖能取聲,不解用指,手勢煩雜,歇指不當,五也;

Playing for many years yet producing chaotic sounds, failing to grasp the five tones, plucking strings but not understanding fingering, resulting in messy hand movements and incorrect stopping of notes. - 調弦不切,聲韻不律,動失正意,聽無真聲,六也;

Tuning the strings improperly, producing unharmonious tones, playing without true intent, resulting in false sounds. - 彈琴之時,吟猱過度,節奏失宜,音韻繁雜,自以為能,有失古意,七也。

Playing with excessive vibrato and excessive rhythm, creating overly intricate melodies, believing oneself skillful but losing the ancient aesthetic.page 9 of Shilin Guangji, QQJC I/21a

- 小病有五 Five lesser faults

- 彈琴之時身側欲偏;手勢繁亂,打絃用指輕重不鈞,一也;

Leaning over while playing, resulting in unbalanced posture; having chaotic hand movements so that when plucking the strings the touch is imprecise. - 若左右緫用甲其聲焦枯,雖有悲思,全無韻聲,不鈞平,二也;

If left and right fingernails are used too much, the result is dry and brittle sounds; so in spite of feeling emotions (the resulting sound) has no resonance or balance. - 左右手用肉多,其聲濁鈍;音韻不清,取聲繁重,散其清爽,三也;

The flesh of the left and right fingers is overused, making the sound muffled and dull; the tones lack clarity, the sound is too ponderous, and thus it is no longer bright and fresh. - 左右用甲多肉少,音韻不;取聲輕重重疊,句度急燥,不較音韻,四也;

Left and right hands use nails more and flesh less, leading to uneven tone quality; inconsistent dynamics lead to muddled sound, rushed phrasing, and diminished tonal quality. - 取聲遲遟,緩音律不續,句度不成,調弄無味,五也。

Producing sound that is sluggish, leading to disjointed rhythms, incomplete phrasing, and melodies that have no flavor.

- 論十二病揔括 Summary of Twelve Faults

蘇翰林易簡曰 Su Yijian nicknamed Hanlin (from having served there) said:凡彈琴蓋以寓意調性,適一時之意,以閑暇簡靜為本。

When playing the qin, one must harmonize one’s intent with the nature of the mode, allowing the music to suit the moment's sentiment, while grounding it in leisure and tranquility.句度節奏不得過多,取聲倫比不欲隔越。

Phrasing and rhythm must not be overly elaborate; tones must be harmonious rather than disjointed.用指甲肉相兼,則其聲清美。

The use of fingernails and flesh must be balanced to produce clear and beautiful tones.右手去弦不得太高,亦不能絕音而拋琴曲;亦不能按著別絃。

The right hand must not rise too high from the strings, nor should it abruptly cut off the sound and abandon the qin melody; it also should not accidentally press other strings while playing.兩手必欲相附如雙鵉,對無舛兩鳳同翔。

Both hands should coordinate like paired luan birds, moving flawlessly like twin phoenixes soaring in harmony.使徽不可誤按,彈絃不可錯鳴。吟猱不可不盡起伏,不可無法段疊,不可不曉句讀,不可無節。

With regard to the hui markers one must not press down in incorrect positions or strike the wrong strings. Fast and slow vibrato cannot but fully express their nuances, you cannot be without having careful phrasing, you cannot be unaware of when to insert appropriate pauses, and you cannot be without rhythm.置琴於前,身湏卓然,先定神氣。兩手視之若無琴;然取予作用,湏作精神,心志絕慮,情意專註。

When placing the qin before oneself, the posture must be dignified, the spirit settled. Both hands should move as though there was no qin (separate from oneself). Yet actions must be purposeful, the mind free of distractions, the emotions totally engaged.不得用力努張精神。不得令筋骨寬緩,肩甲手擘悉欲調暢。按弦用力,勿令人知。

One must not exert force excessively or with too much tension. Do not allow the muscles and bones to be too relaxed, while the shoulders, arms, and fingers must be well-coordinated and fluid. When pressing the strings use force without allowing people to be aware of this.輕重急慢不得斷續,用指手勢悉依法度,取予疾徐皆湏得體。

Light and heavy, fast and slow must not change abruptly. All hand movements and finger positions must follow proper rules, while plucking techniques and speed must be appropriate.目視左手,耳聽其聲,目不別視,耳不別聽,心不別思,志不雜註。

The eyes should watch the left hand; the ears must listen to the sound. The eyes should not wander, the ears should not be distracted, the mind should not drift, the intent must not waver.無問有人無人,又須尊嚴如對長者,一則聲韻雅正,二則感動幽明;

Regardless of whether one is alone or in the presence of others, one must maintain dignity as though facing an esteemed elder. If one is alone then the sound must be refined and proper; if someone else is there (the music) should move both the visible (person) and the unseen worlds.苟亂作太勞,精神疾遽,不若置琴而默坐。古人謂但識琴中趣,何勞弦上聲是也?

If playing becomes careless and energy exhausted, it is better to put aside the qin and sit in silence. The ancients said, "If one understands the meaning within the qin, why labor over the sound on the strings?""彈琴戒謹之病極多,諸家琴書互載之矣。攻琴君子若能精思絕此十二病,擇其善而去其失, 即得絕妙也。若夫天性聦明,取聲奇異,性出於聲,聲出於心,此殆神妙又不可論此也。

The errors to watch out for in qin play are numerous, and qin texts from different schools all record them. A gentleman studying the qin, if able to diligently correct these twelve faults and remove what is improper while preserving what is good, will achieve mastery. However, for those with natural talent, whose sound emerges as unique and extraordinary, whose nature emerges in the music, whose music comes directly from the heart, then this infringes on the divine, and is beyond the scope of ordinary discussion."- 整琴要訣 Qin Maintenance Essentials (not in Taiyin Daquanji)

古琴冷而無聲者,用布囊炒砂罨;候冷,易之數次。而又作長甑,候有風日,以甑蒸琴,令汗溜, 取出吹乾,其聲仍舊。琴无新舊,常宜置床上近人氣,被中尤佳。琴弦久而不鳴者,綳定一处,以桑葉捋之,鳴亮如初。大凡蓄琴之士,不論寒暑不可放置風露中及日色中,止可於無風露陰煖处置之。If an old qin is cold and produces no sound, use a cloth bag filled with heated sand to warm it. Repeat the process several times. Alternatively, place the qin in a long steamer on a windy day, allowing it to sweat, then remove and air-dry it to restore its original sound. Whether new or old, a qin should always be kept near the body’s warmth, such as on a bed. If strings become unresponsive, secure them in place and rub them with mulberry leaves to restore their clarity. In all cases, those who keep a qin must never expose it to wind, dew, or direct sunlight. The instrument should only be placed in a warm, shaded location free from dampness.

- 彈琴之時身側欲偏;手勢繁亂,打絃用指輕重不鈞,一也;

Further comment on rules of play

Today the best known coherent sets of such rules - or perhaps better, descriptions of what is desirable in qin - are described in the two following works:

Some say the 10 Rules attributed to Wu Cheng are a forgery and were probably based on the writings of Xu Hong. Meanwhile, the writings of Xu Hong have been widely discussed, as they are on a page in chinaknowledge.de.

One thing particularly noteworthy about these latter two essays is that they say very little about rhythm, apparently leading people such as Van Gulik to claim that qin music is all about the tonal color of notes. The fact that the writings on qin play such as those on this page, as well as in other books from the Ming dynasty and earlier, spoke quite a bit about rhythm - though admittedly not elaborating a lot about the details - might support the idea that the essay attributed to Wu Cheng should really be dated much later.

However, one might also argue that the writings of people like Xu Hong might suggest that it was only late in its history that qin music put much less emphasis on melody: earlier writers on qin aesthetics seem quite insistent on melody, not just color.

Perhaps further research will shed more light on that issue, but from what I have read the de-emphasis on melody is very questionable. Thus, the later writers may not have written about rhythm as much as earlier writers did, but I have also not seen direct evidence suggesting they thought it was not important.

| Addendum: Materials from the Taiding edition of Shilin Guangji | Another edition of Shilin Guangji, QQJC I/22 |

Qinqu Jicheng, in addition to the edition above, includes the excerpt at right from the Taiding edition. There are in fact at least three known edition of Shilin Guangji; these can be referred to as the Taiding, Chunzhuang and Zhengshi editions (details), with the latter two said to be identical (though see the footnote below). The Chunzhuang edition is above, the Taiding edition is shown at right. Versions of the section of Shilin Guangji that quotes passages attributed to Chen Zhuo are discussed at some length in the book by Yang Yuanzhen discussed under Chen Zhuo's surviving writings. This also includes a folio page from the Zhengshi edition, shown below.

This page from the Taiding edition includes (see at right)

Although there are also some other differences, the Taiding edition includes mostly material the same or very similar to that in the Chunzhuang edition. As mentioned, it ends with the 琴譜直解 explanation of clusters mentioned above (also see this closeup), but the most obvious difference is the addition of the illustration (closeup below; expand) of a gentleman playing the qin. For an unexplained reason this seems to have replaced (or been replaced by) the picture of Confucius playing for his students, also just to the left of a diagram of the front and back of a qin (see above).16

Text begins and ends, "(家語云:子路....歌南風)", the same as for the first and third essages in the image at top but skipping the one in the middle attributed to Chen Zhuo. There is then the image of the two sides also of a jiao wei (scorched tail) qin and finally the image of an unidentified qin player.

|

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a separate page) |

|

1.

Shilin Guangji 事林廣記 (QQJC I/15-22 [11-16 in earlier edition])

(244.xxx? The title Shilin Guangji translates literally as "Affairs-Forest-Broad-Record".

Zha Fuxi's preface says Chen Yuanjing (see next footnote) 編纂 compiled it. Zha does not discuss its possible relationship to another work attributed to Chen, 歲時廣記 Suishi Guangji.

According to the introduction by Zha Fuxi, Shilin Guangji was compiled by Chen Yuanjing during the Southern Song dynasty, then was revised several times during the Yuan dynasty. Three editions are known to have survived:

The third edition (Zhengshi edition) is identical to the second, so Qinqu Jicheng prints only the first two (though see this footnote with one folio page from the Zhengshi edition). QQJC I/17-21 has 9 folio pages from the Chunzhuang Shuyuan edition; I/22 has 2 folio pages from the Taiding edition.

Perhaps because much of the surviving editions of Shilin Guangji were added during later editions, Zha spends some time describing characteristics of the tablature in Shilin Guangji, to show they do date from the Song dynasty.

An essay (.html from .pdf) by Wang Chenghua, Art and Daily Life: Knowledge and Social Space in Late-Ming: Riyong Leishu, says,

A preliminary essay by Lowell Skar, "Charting a New Itinerary of Perfection in Medieval China: The Formation and Uses of the Diagram on Cultivating Perfection (Xiuzhen tu" (2000), says as follows,

A backgammon website has an illustration from Shilin Guangji showing two backgammon players.

The FIFA website says that Shilin Guangji "gives details of the technical elements of conventional football", including a woodblock illustration.

Pian's Sonq Dynasty Musical Sources and their Interpretation transcribes, in addition to these qin melodies, the

Seven melodies on popular notation from Shilin Guangui.

2.

Chen Yuanjing 陳元靚 (1200 - 1266)

3.

Image top right: front page of this edition

5.

Shilin Guangji, General Comments on Qin Tablature 事林廣記,琴譜緫說

6.

(Confucius') Household Sayings (孔子) 家語 (Kongzi) Jia Yu

Note in the translation above that many of its details are also elsewhere. Regarding the added passage, for example, in 高濂 Gao Lian(?) the information about yin and yang wood is the same, but placed at the front, "琴取桐為陽木、梓為陰木。是以造琴之法。...." Regarding the type of wood, translating 桐 tong and 梓 zi is problematic as they are uniquely ancient Chinese; the important factor is heavy (dense) wood vs light wood.

7.

Chen Zhuo Canjun, Qin Shuo 陳拙參軍琴說

Compare the translation there

8.

《帝王世紀》曰 Diwang Shi Ji says,

9.

Illustration 圖: top and bottom of a qin

10.

Illustration of Confucius at the Apricot Pavilion (Xing Tan)

11.

Finger technique explanations

12.

Tablature for the 琴譜 qin melodies (QQJC I/12-14)

13.

Kaizhi (Prelude): Golden Oriole (QQJC I/19)

14.

詞牌黃鶯兒 Ci structure: Huang Ying Er

and

97: 50+47

(Something is wrong with the count.)

15.

彈琴宜忌 Do's and don'ts of qin play

(Return)

Chen (42618.105; Bio/1364; N.D.), according to the afterword by 劉純 Liu Chun (Bio/622? early Ming) to Chen's 歲時廣記 Suishi Guangji, was a reclusive gentleman. He signed himself 廣寒仙裔 Guanghan Xianyi (Lunar Descendant of Immortals?). 16686.67 歲時廣記 says Suishi Guangji had four sections divided according to four time periods. It is not clear how much of the book still exists, or whether Shilin Guangji was a part of it.

(Return)

It is continuing on from the volume as described in the previous footnote.

(Return)

Consists of the essays discussed in the following three footnotes. Compare this with Taiyin Daquanji, Folio 5, Part 1, in particular the translation of the

complete original text. In general it is

almost the same.)

(Return)

The original text here in Shilin Guangji is also online

here.

(Return)

The original text was translated with the nearly identical version in

Taiyin Daquanji, though it adds glosses (音釋 yinshi) and changes its version after the * added near the end).

(Return)

The same information is also here.

(Return)

The names for the parts of the qin are translated

elsewhere on this site.

(Return)

This is where Confucius is said to have taught his disciples. This site also has other illustrations of Confucius playing qin for his students. Sometimes it seems that Xing Tan could also be translated as Gingko Tree Pavilion (further).

(Return)

There is no general title for this part, which has the three sections only titles for each of the three subsections, left, right and clusters. A more complete example of such explanations can be seen in such resources as

Taiyin Daquanji, for example, here

and here.

(Return)

The recording for the Kai Zhi is linked here while those for the five modal preldues are linked here.

(Return)

The specific commentary begins above.

(Return)

Not yet studied carefully. Two typical patterns, 95 and 97 characters each, are outlined in Baidu. The two patterns outlined there are:

7.4,4,4,4.

6,5.6,4,4.

2,5,5.4,4,6.

6,5.6,5.

7.6,6,6.

6,5.6,4,4.

2,5,5.4,4,6.

5,5.6,5.

(Return)

Summarizing these rules, the 13 overall entries are:

12 or 13 sets of rules for playing qin (image with original text)

Su Yijian (958-997) was a Northern Song writer and poet perhaps best known as the author of 文房四譜 Wenfang Sipu; www.chinaknowledge.de tells of this and his Hanlin connection. (Don't confuse with 薛易簡 Xue Yijian, who was a Hanlin Daizhao.)

Attributed to Su Yijian, these were unnumbered and do not correspond with the 7+5 of the previous two. Thus in my translation the arrangement of these "12 faults" into 12 sections can be seen as somewhat arbitrary.

This last section, though also highlighted in black, does not seem to be considered one of the 12 (groups of) flaws.

As discussed above, these rules are found in a number of early handbooks (see, for example, in

Taiyin Daquanji, Folio 6, which seems verbatim but does not include #13).

For a quite different type of rules see

冷謙 Leng Qian

(?),

Sixteen Rules for Qin Tones (琴聲十六法 Qinsheng Shiliu Fa).

(Return)

| 16. Materials from the 泰定本 Taiding and 鄭氏 Zhengshi editions of Shilin Guangji (QQJC I/22 and Yang/297-300) | Compare above and at top |

The illustration at right showns one folio page from the

Zhengshi edition of Shilin Guangji. It was copied from Yang, pp. 299-300. Comparing it to other editions one can see it has omitted the passage from Diwang Shiji. The left hand page begins "引者貴乎...."; this can be found in this text version of Qin Shuo, where it is punctuated "引者,貴乎".

The illustration at right showns one folio page from the

Zhengshi edition of Shilin Guangji. It was copied from Yang, pp. 299-300. Comparing it to other editions one can see it has omitted the passage from Diwang Shiji. The left hand page begins "引者貴乎...."; this can be found in this text version of Qin Shuo, where it is punctuated "引者,貴乎".

(Return)

Return to the annotated handbook list or to the Guqin ToC.