|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| SQMP ToC / trace lyrics Scroll "Short Version" 18 Sections: 1597 version North and Central Asia | 聽錄音 Recording with transcription / 首頁 |

|

47. Grand Version of Nomad Reed Pipe

1

- Huangzhong mode:3 1 3 5 6 1 2 3 |

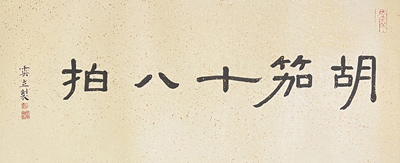

大胡笳

2

Da Hujia |

| See Illustrations for 18 Songs of a Nomad Flute |

"Hujia", literally "nomad reed pipe", is the name given to a variety of reed aerophones associated since antiquity with nomadic groups in what is today western China. It is in particular connected to the story of the abduction ca. 195 CE of Cai Wenji and her 12 years in captivity with a nomadic tribe and giving birth to two children whom she has to leave behind when she is ransomed by

Cao Cao and returned home to Luoyang. The plaintif cry of the reed pipe epitomizes her grief. Although this is a sound that hardly can be replicated on guqin, the present melody does seek to express the grief otherwise.

"Hujia", literally "nomad reed pipe", is the name given to a variety of reed aerophones associated since antiquity with nomadic groups in what is today western China. It is in particular connected to the story of the abduction ca. 195 CE of Cai Wenji and her 12 years in captivity with a nomadic tribe and giving birth to two children whom she has to leave behind when she is ransomed by

Cao Cao and returned home to Luoyang. The plaintif cry of the reed pipe epitomizes her grief. Although this is a sound that hardly can be replicated on guqin, the present melody does seek to express the grief otherwise.

Cai Wenji's abduction took place around the time of the death of her father Cai Yong (133-192). As for her ransom 12 years later by Cao Cao, it took place while Cao Cao was still a Grand General supposedly loyal to the Han dynasty. The title given him in the preface below, Wei emperor Wu Di, is one postumously bestowed on him by his son, Cao Pi, who proclaimed himself Wei emperor Wen Di when his father died in 220.

Besides with the present melody, the same story is also told in her biography as well as in a number of poems and paintings, not to mention in traditional Chinese opera.

As for surviving qin melody versions, these can be grouped as follows (see also the appendix below):4

- Da Hujia (Grand Version of Nomad Reed Pipe; the present melody), surviving in six handbooks from 1425 to 1634. The commentary suggests it was copied down by the famous Tang dynasty qin player Dong Tinglan based on a version played by one 陳懷古 Chen Huaigu.

- Xiao Hujia (Short Version of Nomad Reed Pipe; #15 in Shen Qi Mi Pu Folio One), surviving in four handbooks through 1585. The commentary also attributes this version to Dong Tinglan, though perhaps again this was from Chen Huaigu.

- Hujia Shibapai (Nomad Reed Pipe in 18 Sections).5 This title in connection with surviving qin tablature seems first to occur in this extended qin song with lyrics apparently by Cai Wenji herself but set to what seems to be a new melody unrelated to the previous ones. It is discussed under its first surviving version, in Luqi Xinsheng (1597); it was reprinted in 1611, but apparently then disappeared until there was a modern reconstruction.6

- Hujia Shibapai (as above). This, the instrumental version commonly played today, has some connection to the 1425 version but actually dates largely from the Qing dynasty; its earliest publication seems to have been in 1689.7 There seems to be quite a lot of variety within these latter versions and the actual lineage of the version most commonly played today is not very clear; certainly its musical connection either to Dong Tinglan or Cai Wenji is very tenuous.8

Summing this up in chronological terms,

- In Ming dynasty qin handbooks the most common titles of melodies on this theme are Xiao Hujia (four occurrences to 1585) and the present Da Hujia (six occurrences to 1634).

- In contrast, after an interlude that included publication of the extended qin song called Hujia Shibapai, during the Qing dynasty Da Hujia and Xiao Hujia disappeared and, from at least 1689 to 1910, the new instrumental Hujia Shibapai flourished, with versions in over 30 handbooks.9

Today Hujia Shibapai (often given such translations as 18 Blasts of the Nomad Reed Pipe) seems to be the most popular title but all of the above titles can be found in early handbook lists, with Hujia Shibapai sometimes also applied to the versions listed here under Da Hujia. Sometimes the qin melody is attributed to Cai Wenji herself, as with the earliest version called Hujia Shibapai (1597), but more often, and especially in modern commentary, it is attributed to the famous Tang dynasty qin player Dong Tinglan.

Further regarding Hujia Shibapai in the Qing dynasty (and modern?) repertoire, mention has already been made that its tablature can be traced back only to 1689, the Chenjiantang Qinpu. This version introduced a Hujia Shibapai that seems still to be related to Da Hujia but was so different that perhaps it should be considered a new melody.10 The most two identifiable musical characteristics of Da Hujia in Shen Qi Mi Pu are the opening phrase, also found in later versions, and the theme which begins Section 3 and then begins nine later sections.11 This later version keeps the opening phrase but not the repeated theme. Versions related to this one occur in over 25 further handbooks to the 20th century.

Nevertheless, Qinshi Chubian, Chapter 5b1, seems to be generally consistent in its argument that the melodies called Da Hujia and Xiao Hujia can be considered Tang dynasty melodies. Meanwhile, Chapter 6b1-2 argues that the Qing dynasty Hujia Shibapai dates from the Song dynasty. One of its points is that during the Song dynasty the nationalistc sentiments of this story were particularly popular. However, this should also have been true at the beginning of the Qing dynasty, when China again had foreign rulers.12

The pages just mentioned and the analyses in QSCB, Chapters 5b1 and 6b1-2, also discuss the titles and content of various other relevant artistic works in addition to the qin melodies.

In poetry

As for the Song dynasty or earlier, there survive at least three Hu Jia poems in 18 sections that relate this story. These are by (or attributed to):

In addition there survive several poems by people who heard a version of the melody being played. Three notable examples are:

In opera

Of course, the story of Cai Wenji has also been related in various traditional Chinese operas.16

The story of Cai Wenji has also been the subject of several modern operas. For example, at least one Western-style modern opera (with Chinese melodic connections) uses in part the lyrics attributed to Cai Wenji herself as well as portions of the melody from 1722.17

Fine art

The story of Cai Wenji's abduction, in addition to its presence in all performing art genres, is also of note in fine art. The best introduction to this is in the book Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute, by Robert A Rorex and Wen Fong. It was published by Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, following their acquisition of a 14th century scroll illustrating the cycle of 18 poems by Liu Shang. The fascinating illustrations bring the story very much to life. Each of the 18 section titles below is quoted from one of these 18 poems, in sequence, and so one can perform a fully-illustrated Da Hujia by combining the music with the scroll.18 In the last verse Wenji expresses her joy at being able to play the qin again.

More

Although most Chinese music has programmatic titles, in qin music the connection between the images and the melodies is rarely obvious. Da Hujia, however, has several very evocative passages, in particular one in Section 13 where Wenji must leave her children and return home.

Besides my own, silk string recordings of the SQMP version include the ones linked here by

In addition to the above there have been a number of recordings by Gong Yi and others using nylon-metal strings. With so many versions available it is interesting to compare and contrast the differing interpretations.19

There are also a number of recordings of Hujia Shibapai; these seem generally to be related to the 1722 version, which has a melody quite different from that of Da Hujia (further comment in this footnote).

The Emaciated Immortal, in accord with Qin History,21 says

the Official History of Han records:

Later Cao Cao, an old acquaintance of Cai Yong, ordered a great general to ransom Cai Wenji. She returned to Han, (but) her two sons remained with the nomads. Afterward, thinking longingly of Wenji, the nomads would roll up grass leaves for blowing as reed pipes, and play mournful sounds. During the Tang dynasty Dong Tinglan, who was very good at the sounds of the Shen and Zhu schools, wrote down these sounds of the nomad reed pipe for the qin. This was his Grand and Short versions of Nomad Reed Pipe.

(00.00) 01. 紅顏隨虜 The pretty woman (must) follow the nomads (into captivity)

Return to the top

Horses whinny on the frontier.

A solitary goose turns its head,

And its cry resounds, "Ying, ying."

Music (timings follow the recording on

my CD;

聽錄音 listen with

my transcription or

follow the scroll)

18 sections, titled;22

timings from my CD set

(compare other reconstructions)

(00.54) 02. 萬里重陰 Darkened skies extend for 10,000 li

(01.18) 03. 空悲弱質 (At a desert encampment) helplessly resenting her weakness

(01.51) 04. 歸夢去來 Dreams of returning home come and go

(02.39) 05. 草坐水宿 Sitting on the grass and sleeping by the water

(03.35) 06. 正南看北斗 (So far north) it is to the south one looks to see the Big Dipper

(04.25) 07. 竟夕無雲 (Nomad music on) a cloudless night

(05.02) 08. 星河寥落 (As dawn approaches) the stars of the Milky Way thin out

(05.39) 09. 刺血寫書 Pricking blood (from her finger) to write a letter (home)

(07.03) 10. 怨胡天 Resenting the nomad skies (but finding love in the birth of a child)

(07.26) 11. 水凍草枯 Waters freeze over and the grass withers (marking the 12th year in captivity)

(08.10) 12. 遠使問姓名 A (Han) envoy from afar is asking after her name

(08.47) 13. 童稚牽衣 (As she prepares to leave) her (two) children pull at her clothing

(09.39) 14. 飄零隔生死 Drifting around separated (from her family, not knowing if they are) alive or dead

(10.01) 15. 心意相尤 (On the homeward journey) her heart and mind argue

(at having to leave her husband)

(10.40) 16. 平沙四顧 The flat desert is everywhere one looks

(11.04) 17. 白雲起 White clouds rise (as they approach first Chinese garrison town)

(11.37) 18. 田園半蕪 The fields and gardens (of home) were half-neglected,

(but now she can play her qin again, expressing in music her sad story).

(12.04) --- 入無射泛 play harmonics of the wuyi mode

(12.16) --- 曲終 Piece ends

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

| 1. Translating 胡笳 Hu Jia (see under Xiao Hujia for 大 da and 小 xiao) | 胡笳 Hujia |

"Hu Jia" (hujia) has been given a variety of translations, including "nomad flute", "nomad reed pipe", "barbarian reed pipe", and so forth. The following may explain some of the variety.

"Hu Jia" (hujia) has been given a variety of translations, including "nomad flute", "nomad reed pipe", "barbarian reed pipe", and so forth. The following may explain some of the variety.

- "胡 Hu" (30073.000/12 "夷狄名 name of yidi", considered as northern tribal groups)

"Hu" is a term that the Chinese applied to non-Han people or peoples originating north of the Han, ranging from the northeast to Central Asia. As discussed in the Wikipedia article "Wu Hu" (五胡), many peoples called hu were not nomadic, nor were they uncivilized. However, early Chinese literature generally seems to depict them in this way, hence the translations. Specifically (and perhaps in this case) the term often seems to apply to the 匈奴 Xiongnu (Wikipedia). - "笳 Jia" 26511.0 ("胡笳也,笛之一種) says same as hujia, a type of di flute" (no image, though for di 26519 has

this image)

Although said to be a type of flute, the hujia is generally considered to be a reed type instrument, hence "reed pipe". - "胡笳 Hujia" 30073.357 (樂器名....) has the image at right and this text; the earliest reference given is the 14th c. CE 文獻通考 Wenxian Tongkao (Wiki) which in turn cites a 杜摯茄賦 Rhapsody on the Reed Pipe by Du Zhi (3rd c. CE). Meanwhile, this image copied from an unknown online source shows seven potential 胡笳圖 depictions of hujia, indicating just from the name alone one cannot say whether hujia were necessarily flutes or a reed instruments.

For issues in translating pai ("blasts", "songs", etc.), see

another footnote.

(Return)

2.

Da Hujia references (see also QSCB analysis)

5960.738 大胡笳 da hujia says only "樂器名。參見十八拍、沈家聲條 name of a music instrument (sic), see 18 Sections and Shen Family Sounds."

- 2741.174 十八拍 Shiba Pai (18 Sections)

十八拍﹕樂府,琴曲歌辭名。(樂府詩集,琴曲歌辭,胡笳十八拍)唐劉帝(!:商)胡笳曲序曰﹕蔡文姬善琴....

18 Sections: Music Bureau, name of Qin Melody Lyrics (YFSJ, p.860, beginning 3rd line from left) According to Liu Shang's Preface to Hujia Melody, Cai Wenji was skilled at qin.... (tells the story of her capture and later release, adding that "Mr. Dong [Tinglan] used qin to describe the reedpipe sounds....). - 17529.270 沈家聲 (Shen Family Sounds)

宋,樂曲名。(韻會小補)沈遼集大胡笳十八拍,世說沈家聲。又見《文獻統考,樂考》

Song dynasty melody name. (Yunhui Xiaobu) The Shen Liao collection's Long Hujia Shibapai is what is commonly known as the Shen Family sound. See also "Wenxian Tongkao, Music Study".

See also Xiao Hujia, in particular the quotes under Xiao Hujia and Earliest Hujia titles

The poems on this theme attributed to Liu Shang and Cai Wenji, which are included in Yuefu Shiji, Folio 59, #3, are discussed further below. Qinshu Daquan (see QQJC, V, pp.261-268) also has these, plus one by Wang Anshi (1021-86; see below) and some additional material.

(Return)

3.

黃鐘調;即無射 Wuyi (or Huangzhong) mode

For this tuning, slacken 1st, tighten 5th strings each a half step. For more details on this mode see Shenpin Wuyi Yi. For more on modes in general see Modality in Early Ming Qin Tablature.

(Return)

4.

History of Hujia titles

In the earliest known melody list, dated to the 7th century or earlier, Hujia seems to be only a mode name. Song dynasty lists include both

Da Hujia and Xiao Hujia. As for "shibapai", I have not found much mention of this as a qin melody title prior to the Song dynasty. In fact, Seng Juyue includes a

"Da Hujia Shibapai" only amongst its "less ancient" melodies.

On the other hand, Qinshu Cunmu suggests an early origin for Hujia Shibapai. Thus, although surviving melodies with this title do seem to be more recent than those with the titles Xiao Hujia and Da Hujia, the title Hujia Shibapai itself is not necessarily more recent. For more on this perhaps one should search in other media for occurrences of these titles.

(Return)

5.

胡笳十八拍 Hujia Shibapai

For comment on the difficulty of translating this title, see

above and under

1598. Note also that Hujia Shibapai is included in Zha Fuxi's index under Da Hujia (see the Appendix below).

(Return)

6.

Hujia Shibapai as a Qin Song

The earliest Hujia Shipapai set to lyrics, dated 1597, is introduced separately. The modern reconstruction must have achieved some popularity as when I presented my own reconstruction to some friends they recognized the melody from having heard it earlier.

(The Da Hujia set to lyrics in

>1505 uses the same melody as in 1425; the lyrics seem to be new and properly paired, but are not naturally adaptable for singing.)

(Return)

7.

Qing dynasty Hujia Shibapai: created ca. 1689 or dating from Song dynasty?

The version of Hujia Shibapai commonly played in the Qing dynasty (see comment on its survival) is the one first published in Chengjiantang Qinpu (1689), but today it is best known from the very similar version in Wuzhizhai Qinpu (1722). In Guqin Quji, Vol. I (pp. 135-151) there is a transcription of the 1722 version according to Wu Jinglue ("14:07"), for whom there are recordings (e.g.

here and

here [listen, but both "15:36"]. It is also transcribed, but with somewhat different note values, in

The Qin Music Repertoire of the Wu Family). In QSCB,

Chapter 6b1-2, Xu Jian (who in a previous chapter had discussed Da Hujia and Xiao Hujia as Tang dynasty melodies but does not seem to mention anywhere the 1597 Hujia Shibapai) analyzes the 1689 version according to the 1722 version, concluding that this version dated from the Song dynasty. He gives little musical argument to support his opinion. The Wu Jinglue recording and transcription show that this version has a few melodic similarities with Da Hujia. The fact that Da Hujia survives first from Shen Qi Mi Pu (1425), a handbook noted for collecting earlier tablature, then later survives in only a few handbooks and with little variation, supports arguments for its antiquity: if it was highly respected but not part of the active repertoire, people would simply re-copy existing tablature. The five versions of Hujia Shibapai published between 1689 and 1722 might similarly suggest this was transmission of an earlier version except that, unlike Shen Qi Mi Pu, the 1689 handbook is not noted for having copied very early tablature; this then might more likely suggest the modern version, in spite of its having being inspired by the earlier melody, was largely a newly created piece.

(Return)

8.

Survival of Hujia Shibapai into the modern repertoire

Although the version recorded

here by Wu Jinglue (see analysis above) has its earliest publication later than other Hujia, it is not clear whether one can say it actually survived into the modern repertoire or whether Wu or someone else revived it. There are also recordings of Hujia Shibapai by Guan Pinghu and

Cai Deyun, but both mention only 1722 as their source, not a living tradition. In this regard it should be noted that there have been several reconstructions published of the 1425 Da Hujia (in addition to my own and those of Guan Pinghu and

Yao Bingyan), and it may well be that today one is as likely to hear one of these interpretations as one of the Qing dynasty ones.

(Return)

9.

Tracing Da Hujia (see Tracing chart and compare Xiao Hujia)

As the tracing chart for Da Hujia, based on Zha Guide 8/77/119 shows, the early versions are all closely related to the 1425 Da Hujia, with very similar music and sub-titles all connected to the story as told in Liu Shang's poem. These occur in five handbooks from 1425 to 1596, then once again in 1634. The 1525 version is called simply Hujia and the 1634 one, though called Hujia Shibapai, is a copy from 1525. The later versions of Hujia Shibapai, though very different, are also included in this chart. In fact, it seems that the 1689 version continued throughout the Qing dynasty and is thus the true ancestor of the Hujia Shibapai usually played today. The dramatic change in the 1589 version suggests that, although the old tablature survived and people sometimes played from it, it wasn't being played fluently, or at least not consistently so. Finally someone doing a new interpretatioon had their version copied down into tablature, hence the tangential connection to the earlier version. Further regarding this, compare the development of melodies from Shen Qi Mi Pu Folio 1.

(Return)

10.

Origin of the Qing dynasty version

Xu Jian argues (see above) that this 1689 version actually originated in the Song dynasty; to the extent that it is sufficiently different from Da Hujia it is still a "new" melody, even if it dates from the Song dynasty.

(Return)

11.

Repeated motif

Described as 從卷至盧 "From Roll to Reed"; see sections 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12 and 15.

(Return)

12.

Dating the Hujia melodies

For Xu Jian's commentary on Hujia in Qinshi Chubian, see Chapter

6a2 as well as Chapters

5b1 and

6b1-2.

The biography of 董庭蘭 Dong Tinglan (not yet translated) also has relevant information.

(Return)

13.

Hujia poem attributed to Cai Wenji

(see original text)

There is an early poem on this theme attributed to Cai Wenji (蔡琰 Cai Yan) herself, called

Song of Grief and Resentment (Bei Fen Shi; see its original text; it is translated in Paul Rouzer,

Articulated Ladies, 2001). It is also briefly quoted in the SQMP preface, as follows,

孤雁歸兮聲嚶嚶。」 A solitary goose turns its head, its cry resounding "ying, ying."

As for the earliest known publication of the Hujia Shibapai poem attributed to her today, it cannot be found earlier than the Song dynasty, two early sources being the 12th century Yuefu Shiji, Folio 59, #3 (pp. 860-865), or in the Afterword to the Songs of Chu by Zhu Xi of the Southern Song dynasty (see QSCB, Chapter 6b1-2). YFSJ says its poem is the original one, later imitated by Liu Shang. However, the Liu Shang poem, also a first person narrative, is known to have had some popularity during the late Tang, so it could well be that the poem attributed to Cai Wenji herself was the imitation. See Idema and Grant, p. 121ff. It is translated there as well as in Chang and Saussy, pp.22-30.

(Return)

14.

Hujia poem by Liu Shang

(see original text)

This poem by 劉商 Liu Shang is in Yuefu Shiji, Folio 59, #3. There is a translation in Robert A. Rorex and Wen Fong, Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute, A Fourteenth-Centry Handscroll in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1974. The scroll is discussed above. There is a copy of the scroll linked from

another page, which also has

the complete original text.

(Return)

15.

Hujia poem by Wang Anshi

(see original text)

王安石 Wang Anshi (1021-86) is discussed under Qinshi Chubian,

Chapter 6. His Hujia poem apparently has not been translated.

(Return)

16.

Traditional Chinese operas on the Hujia theme

These include Wenji Goes to the Desert (文姬入塞 Wenji Ru Sai) and Wenji Returns to Han (文姬歸漢 Wenji Gui Han); both are discussed in LXS.

(Return)

17.

Modern musical settings of the Hujia story

There have been several orchestral arrangements based on or inspired by one of the early Hujia melodies; some of them have included lyrics. Usually the original melodies are simply arranged for another instrument or for orchestra. Two such examples are:

- "蔡文姬 Cai Wenji", an orchestration by 史志有 Shi Zhiyou of the music in sections 1, 12 and 18 of Wang Di's transcription of the 1597 Hujia Shibapai; in October 2009 I found a partial recording online but it has seend been moved or removed (try searching for "史志有" "蔡文姬")

- Sections from the same melody played solo on a 葫蘆絲 hulusi (Wiki); available on YouTube.

In contrast to these is an opera by Bun-Ching Lam, which uses material (generally quite altered) from the Qing dynasty Hujia Shibapai.

Lam's work is definitely new, drawing inspiration from qin materials.

18.

Hujia Scroll

Some societies have a tradition of illustrated narrative storytelling. For example, in Rajasthan itinerant storytellers might as they go along point at a backdrop illustrating their story. Although a narrative series such as that in the Hujia scroll might seem ideally adapted for this sort of event, I am not aware of such a tradition in China.

19.

Comparing different interpretations of Da Hujia

In this regard it is interesting now, having long finished production of my Shen Qi Mi Pu CD set, to look at some other interpretations. Perhaps an analysis of Da Hujia Section 13 is particularly relevant. Here (08.47 of my recording; see also Section 13 of my linked transcription) there is a persistent use of a sharpened 5 (G# in the transcription). To me this is a deliberate attempt to portray Cai Wenji's extreme emotion at having to leave her children (hearing them cry?). This passage can be heard in the other five linked recordings as follows:

The first three, all done before the Cultural Revolution when everyone in China still used silk strings, all change the non-pentatonic notes. The latter two, done after my recording, both keep them.

Regarding the transcription, mine has the open string as "1" because that is what it must be if the scale follows the traditional Chinese pentatonic scale of 1 2 3 5 6 (do re mi so la). I treat staff notation as though it is Chinese traditional relative pitch notation so in this tuning the first string is c. The actual modality, as discussed here is mostly la - mi, though it often switches to do - so).

Conservatories in China, however, either assume or demand that for standard tuning the open first string be tuned to the Western standard of A=440 HZ. For this tuning the first string is lowered a whole tone and so the linked transcription of Yao Bingyan's performance has the first string as Bb. The transcription of Section 13 shows no changes from the indicated tuning.

20.

For the original Chinese text see 大胡笳.

21.

琴史 Qin Shi

22.

Section titles

Return to the top

Appendix 1

In the tentative translation below "Hu" refers to the nomadic people who took Cai Wenji. As for pairing these words with the music here, it generally follows the traditional method but this is difficult to follow here, in particular because the repeated texts are not indicated (except in Section 1). The tablature also does not make it clear whether the repeats are only of the music or also of the lyrics (this within the context of it not being clear whether one should actually sing the lyrics at all.) Of particular note, the titles of each of the 18 sections come from a phrase in the corresponding section of the famous poem on this topic by Liu Shang: see it combined with

images from the related scroll painting. This also brings a closer connection between the lyrics and the corresponding music.

紅顏隨虜何苦,。狂風花落兮春殘無主。捲蘆那為笳兮,,將愁訴,,嘆離鄉兮失土。

萬里重陰漠漠,邊城兮蕭索。顏如花兮,命可奈何兮如葉薄。

(卷)空悲的弱質,胡漢豈宜家室。(盧)

(從卷至盧) (從卷至盧)

(從卷至盧)(從天至地) 雲彩連宵無寐,殘生南歸。抱胡兒兮淚下沾衣,兒傷悲。問天無語食誰知,生別兮死別其何異,萬事都成非。嗟,二兒,晨昏脫衣起臥依誰隨,暑寒飢渴的那依誰語。嗟,二兒。

星河寥落雲漠漠,擬問天橋,何日填鳥鵲。牛女遙通,許我歸相約。厭聽胡笳愁黯黯,吹胡角,秋風壑,天寒日暮成蕭索。憶兒心奈何,號母聲失卻。胡兮漢兮,殊方天一各。我復愁門戶誰開愁鎖鑰,那有醫愁藥。渴飲井泉,飢食肉酪。酪。

(從卷至盧) (從卷至盧)

(從卷至盧) (從卷至盧) 別離多情重稚兩牽衣,別離子母兩東西,黃金贖阿歸。嗟別離,河梁恩愛手相攜,四野煙塵迷。母兮的那別兒,兩意臨歧恨不步相隨。忿怨兮無人知,兩淚交垂,聽胡笳兮聲又悲。添愁緒,父母無嗣,取阿歸兮蔡蔡氏承宗系。不違忠孝,兩全恩義。父子兮死生重遇,骨似同氣。

飄零隔生死,母兮遙憶子。不知其所以,那欲衣欲食兮誰取。長江滾滾,何時是止,相思無已真無已。

(從卷至盧) 平沙那四顧,別胡入漢兮天連樹。雪霞海曙,片心回護,丟兒最苦。

白雲兮四起,長城那萬里。遙舉吾兒之所止,邊城胡地,生遂南歸兮,一悲也一喜。

中華田園半蕪,於阿方還家,海天賒。南枝上笑妒那梅花,依舊玉絛瑕。思兒兮學奏胡笳,周南兮大雅,今傳天下。

江春水向東流。

Appendix 2

18 Songs of a Nomad Flute: a new creation

This opera by Bun-Ching Lam (Wenji: Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute, 2002) has a libretto by Xu Wenying that uses selections of the poem attributed to Cai Wenji herself. However, instead of drawing on qin music from 1597, Lam's opera adapts its from sections 1, 6-7, 13-14 and 16-18 of a transcription of a performance of the 1722 version of Hujia Shibapai played by 吳景略 Wu Jinglue as published in 古琴曲集 Guqin Quji, Vol.1 [Beijing, 1962], pp.135-151 (the original 1722 tablature is followed by the Cai Wenji lyrics, but they do not match the music by the

traditional pairing method). Her rhythms are somewhat different from those in the performance by Wu on The Qin Repertoire of Wu Jing-lue, ROI RB-981014-2C, Hong Kong, 1998, so the transcription was presumably made from a different recording. The transcription, by 許健 Xu Jian, uses polyrhythmic meter to try to capture the nuances of Wu's free rhythms. Lam interprets these changing rhythms quite strictly. In her version some of these excerpts are played in a recognizable manner; others are quite altered, e.g., by playing them at about 1/4th the speed.

(Return)

I have shown this scroll at small gatherings, where someone can unroll the scroll as I play, and also as part of a stage performance where the images are projected using PowerPoint as I played the melody. I have not yet been had the opportunity to do this while someone recites Liu Shang's poem.

(Return)

It is not clear to what extent these players consulted other interpretations when making their own. When I did my original reconstruction in the 1980s, although I had already heard the version by Guan Pinghu, I had not studied it carefully. By the time I started on Da Hujia I had noted that Guan generally changed non-pentatonic notes into pentatonic (see in particular comments under Guangling San) and had for a long time decided that, unlike when I was beginning doing reconstructions, I would studiously avoid looking at other people's interpretations so as to ensure I was doing an independent reconstruction

(further rationale).

(Return)

(Return)

It is not clear if this is a book name or just the history of qin. Zhu Quan's sources are problematic. It is similar to but not directly from the version in Zhu Changwen's Qin History.

(Return)

Each section title is taken from the respective poem in the set of 18 poems by Liu Shang. The words added in brackets here are meant to help connect the section titles to the themes of Liu Shang's poems.

(Return)

Lyrics for the Da Hujia from Zheyin Shizi Qinpu (>1505)

With translation (compare 小胡笳 Xiao Hujia and 劉商 Liu Shang)

From QQJC I/255-9; Comment

A Fair Face Taken by the Nomads

A fair face taken by the nomads how bitter! (repeat) —

In these mad winds flowers fall; spring is spent, and no one to take care of her.

Rolling reeds to make into a nomad reed-pipe (repeat) to voice this sorrow (repeat);

lamenting the loss of homeland and native soil.

Heavy Gloom for Ten Thousand Li

For ten thousand li, layered gloom lies dense;

the frontier city is bleak and desolate.

A face like a flower—

yet what can fate do, when life is thin as a leaf?

Vain Lament for her Frail Body

腥羶蟻類兮,於我也難為匹。捲蘆兮,為笳兮,悲風冷月何抑鬱。寒雲蔽日,塵沙漠漠天迷沒。眉蹙遠山總成那愁戚,虜騎胡姬俱莫識。

(Roll) Vain sorrow for this frail body:

how could Hu and Han ever form a proper household? (Leaf)

Rank smells and coarse creatures—

to me they are impossible to match.

Rolling reeds, made into a nomad reed—pipe;

bitter winds and cold moon, how stifling this grief.

Cold clouds blot out the sun;

dust and sand blur the sky into nothingness.

Brows knit like distant mountains, all becoming sorrow;

barbarian riders and Hu women alike, none recognize me.

Dreams of Returning Home Come and Go

去來歸夢蓊難必,栩栩蘧蘧,周與蝶相為一。霜寒風疾,遠塞孤城,氈帳何寥寂。舊事無憑,新愁不失,夢裡還家,虛幻兮無真實。離會都成恍惚,此身羽翼,恨少神仙術。故國兮誰傳消息,胡亭折柳兮,難逢使驛。卷蘆為笳,聊申抑鬱,哽咽胡腔音呂律。風落梅花,字字聽吹出。

(Play from "roll" to "leaf")

Dreams of return come and go, tangled and uncertain—

fluttering, shifting, like Zhuang Zhou and the butterfly, one with the other.

Frost is cold, wind fierce;

distant frontier, lonely city—how empty the felt tents.

Old affairs leave no trace; new grief never departs.

In dreams I return home, illusory, without reality.

Partings and meetings all become hazy;

had this body wings, I would fly back—

alas, I lack the arts of immortals.

Who will carry news of my old country?

At the Hu pavilion, willows are broken—yet envoys are hard to meet.

Rolling reeds become a nomad reed—pipe, to vent this oppression;

the choking Hu tone follows pitch and law.

Wind scatters plum blossoms—

every note is heard as it is blown.

Sitting on Grass, Sleeping by Water

(天)胡俗草坐水宿,隨處行居,氈裘兮茵褥。羯羶為味兮,鼙鼓達夜聲催促。凄涼滿目

(地),

志虧節義,身罹污辱。勞漢使兮,千金收贖。兩兒啼哭,生耶死也,會面良可卜。痛割肝腸骨肉,空鞠育。胡笳動兮邊馬齪,歸雁南北。此心覆也嗟鄉曲,此身腥羶兮須向那長江一沿。

(Play from "roll" to "leaf")

(Heaven) Hu customs: sitting on grass, lodging by water;

moving and dwelling wherever one happens to be,

felt coats and bedding mats.

Goat flesh for flavor;

drums pound through the night, urging on.

Desolation fills the eyes (Earth);

Resolve falters, integrity is broken,

the body suffers defilement.

The Han envoy is wearied;

with a thousand in gold, redemption is gathered.

The two children cry—

will they live or die? Can we meet again?

Pain cuts through liver and bowels, through flesh and blood—

raised in vain.

The nomad reed—pipe sounds; frontier horses stir;

returning geese fly north and south.

This heart overturns — alas for my native place;

this body, rank with barbarian odors, must turn toward the long course of the Yangtze.

(So far north it is) Facing South to Gaze at the Northern Dipper

望斗瞻雲,的那心懸一寸。的那漢家宮殿,胡塞風塵,的那共誰論。重逢聖君,遣千金兮那歸一身。二子兮會無因,兩情兮難具陳。胡笳兮哀樂相均,不堪回首頻頻。

(Play from "roll" to "leaf" then Play from "heaven" to "earth")

Gazing at the Dipper, watching the clouds—

my heart hangs by a single inch.

Those Han palaces—

Hu frontier dust and wind—

with whom can I speak of this?

Reunited with the sage ruler,

a thousand in gold is sent to redeem this single body.

The two children—there is no cause for reunion;

two sets of feelings cannot both be fully spoken.

The nomad reed—pipe balances sorrow and joy alike;

I cannot bear to look back again and again.

Through the Night No Clouds

All night long, no sleep beneath drifting clouds;

this remnant life turns southward home.

Holding the Hu children, tears fall soaking my clothes;

the children grieve.

I question Heaven — no answer;

who knows of hunger?

Living separation and deathly separation—how do they differ?

All things turn out wrong.

Alas — my two children:

at dawn and dusk, undressing and rising,

on whom do you depend?

In heat and cold, hunger and thirst—

to whom do you speak?

Alas — my two children.

Sparse Stars in the Milky Way

The Milky Way lies thin; clouds stretch dim.

I would ask about the Heavenly Bridge—

when will magpies fill it?

The Cowherd and Weaver Girl meet across distance;

grant me, too, an appointed return.

I loathe hearing the nomad reed-pipe, its dark sorrow;

Hu horns are blown,

autumn winds roar through ravines;

in cold twilight, all becomes desolate.

Thinking of my children—what can the heart do?

Calling “Mother,” their voices fail.

Hu or Han—

different realms beneath one sky.

Again I grieve: who will open the locks of sorrow at my gate?

Where is the medicine that heals grief?

Thirsty, I drink from wells;

hungry, I eat meat and curds—

curds.

When you’re ready, just say “Send Section 9”, and I’ll continue one section at a time so nothing gets cut off.

Pricking blood to Write a Letter

愁腸裂,金針刺血,寫個生離別。愁腸寸裂,秘術無傳,難致相逢訣。紙上猩紅,筆端喉舌,驛使你那勞傳,邈然書札。邊城孤妾,身失難持節。戎羯兮有污女,舍生空死訣。綿綿此恨,於誰為雪。愁結胡笳聲哽咽,傷今慨古腸空熱。恨蓄悲銜痛徹,志摧那心欲折。艱阻尋思歷涉,冷冷然攢眉問月。婦人莫作兮,有志難施設。邊地威嚴,雪霜凜烈。滿野那牛羊兮,草枯水竭。上天有眼,不與人分別,神聖為靈,不與人兮垂鑒察。阿未負天阿負阿,此生殊匹依誰說。剛腸空有心如鐵,隆寒盛暑牙空齒。身單于,雪飄飄兮那飛玉屠,愁人愁殺。

(Play from "roll" to "leaf")

Grief rends the bowels;

with a golden needle I prick blood,

writing of living separation.

Each inch of sorrow splits apart;

secret arts are lost—no means to send a meeting pledge.

Vermilion stains the paper;

the brush-tip becomes throat and tongue.

The courier is wearied carrying it;

the letter drifts far away.

A lone woman at the frontier city,

her body dishonored, unable to keep integrity.

Among the Rong and Jie, women are defiled;

casting life aside, death is in vain.

This boundless resentment—

for whom can it be washed away?

Grief knots into nomad reed-pipe sounds, choking;

wounded by the present, lamenting the past, the bowels burn empty.

Hatred accumulates; sorrow is held fast, pain pierces through.

Resolve collapses; the heart is about to break.

Obstacles multiply with every thought and journey;

coldly, brows knit as I question the moon.

Let women not be born—

with will, yet nothing can be accomplished.

Frontier authority stands severe;

snow and frost bite fiercely.

Across the fields, cattle and sheep—

grass withered, water exhausted.

Does Heaven have eyes? It does not distinguish people.

The spirits are numinous, yet do not look down and judge.

Have I not failed Heaven—or has Heaven failed me?

This life unmatched—on whom can I rely to speak of it?

A tough heart, yet only iron within;

in bitter cold and burning heat, teeth chatter empty.

Alone as a chanyu,

snow whirls like drifting jade—

grief kills the grieving.

Resenting the Nomad Skies

胡天天無涯兮地無邊,我心愁絕兮亦復如然。仰望空雲煙,消息難傳。

(Play from "roll" to "leaf")

The Hu heavens have no edge, the earth no bounds;

my heart’s grief is just the same.

I gaze upward at empty clouds and vapors;

news is hard to transmit.

Water Frozen, Grass Withered

動寒風時值隆冬,草枯那水凍,人坐那玉壺中。萬木皆空,造化窮終。水凝雪積,宇宙樊籠,光透那玉玲瓏。見天外一孤鴻,南歸回首匆匆,於阿信難通。嘆邊戎,貂裘戰馬,挾矢張弓,羶氣威雄。秦關西望重重,驛使也難逢。噫漢宮,氣沖沖,仰頭細問天公。

(Play from "roll" to "leaf")

Cold winds stir—deep winter arrives.

Grass withers; water freezes;

people sit as if inside a jade jar.

All trees stand bare;

the work of creation reaches its end.

Water congeals; snow piles;

the cosmos becomes a cage.

Light pierces like jade and crystal.

Beyond the sky I glimpse a lone wild goose;

southward it returns, glancing back in haste.

Alas—trust is hard to convey.

I sigh for the frontier tribes:

sable coats, war horses,

bows drawn with arrows,

rank strength and menace.

Looking west from the Qin passes, layer upon layer;

even couriers are hard to meet.

Ah, the Han palace—

its vital force surges;

raising my head, I question Heaven closely.

An Envoy Asks My Name

勞遠使,問行藏,遭亂荒。身罹胡騎,擬訴事堪傷。文姬蔡琰父,漢中郎,奉違生死存亡,思鄉道路何長。銜哀願為阿訴君王,念綱常。

(Play from "roll" to "leaf")

The distant envoy is wearied, asking of my whereabouts,

encountering chaos and desolation.

My body has suffered under Hu cavalry;

I would speak of it—how grievous.

Wenji, Cai Yan, daughter of a Han Court Gentleman,

parted amid life and death, not knowing survival.

Long are the roads of longing for home.

Bearing grief, I wish to appeal to the ruler,

calling to mind the bonds of moral order.

(As I prepare to leave) Children Clutch at My Robes

At parting, affection deep:

two young children clutch my robes.

Mother and children part, east and west;

gold redeems me home.

Alas, parting—

by the river crossing, loving hands clasped together;

across the four fields, smoke and dust blur everything.

Mother turns away from her children;

at the fork in the road, two wills oppose each other,

resentful that their steps cannot go together.

Anger and grief—no one knows.

Two streams of tears fall together;

hearing the nomad reed-pipe, its sound grows still more sorrowful.

Grief increases:

my parents without heirs;

I am taken home so the Cai lineage may continue.

Loyalty and filial piety are not violated;

kindness and duty are both fulfilled.

Father and child meet again across life and death;

bones seem of one breath.

Adrift, Separated from knowledge of Life and Death

Adrift, cut off between life and death;

a mother, far away, remembers her children.

Not knowing how they fare—

when they want clothing or food, who will provide?

The Long River rolls on endlessly;

when will it ever cease?

Longing has no end—truly, no end.

Mutual Reproach of Heart and Mind

相尤心意,相尤的那尤,萬古千秋。不知天與我仇,我與那天仇。問天兮,不知子為我愁,不知我為子愁。悠悠無語也垂頭,忍恥含羞。

(Play from "roll" to "leaf")

Heart reproaches heart,

reproach upon reproach, for ten thousand ages.

I do not know whether Heaven is my enemy,

or whether I am Heaven’s enemy.

I question Heaven—

it does not know the child’s sorrow for me,

nor does it know my sorrow for the child.

Endless, wordless, I lower my head,

enduring disgrace and holding shame within.

The flat sands are everywhere

Across the level sands I look in all directions;

leaving the Hu and entering Han, sky joins with trees.

Snow-glow and sea-dawn;

this single heart turns back to guard.

Casting off my children is the bitterest pain.

White Clouds Rise from Afar

White clouds rise on all sides;

the Great Wall stretches ten thousand li.

I lift my gaze toward where my children remain.

At the frontier city, in Hu lands—

I live on and return southward,

one sorrow and one joy.

The Fields and Gardens were Half Abandoned

In the Central Plain, fields are half overgrown.

I am about to return home —

sea and sky stretch on credit.

On southern branches, plum blossoms smile in rivalry,

still flawless as jade cords.

Thinking of my children, I learn again to play the nomad reed-pipe.

Zhou Nan and the Great Odes —

now transmitted throughout the world.

Play the harmonics for Wu Yi (modal prelude), then the melody ends.

Shen Qi Mi Pu has the same instructions; the lyrics are the last six characters of those for the complete modal prelude in Zheyin Shizi Qinpu (see in ToC); they are discussed and translated here.)

Any river's springtime waters flow eastward.

Chart Tracing Da Hujia

(compare Xiao Hujia)

Comment; based mainly on Zha Fuxi's Guide, 8/77/119.

|

琴譜

(year; QQJC Vol/page) |

Further information

(QQJC = 琴曲集成 Qinqu Jicheng; QF = 琴府 Qin Fu) |

|

1. 神奇秘譜

(1425; I/149) |

18T; Da Hujia (Folio 3; SQMP puts Xiao Hujia in Folio 1: "Most Ancient");

"Dong Tinglan"

Related versions below are #2,3,4,5,& 9 |

|

2. 浙音釋字琴譜

(>1505; I/255) |

18TL; Da Hujia; = 1425 but Dong Tinglan" |

|

3. 西麓堂琴統

(1525; III/212) |

18T; Hu Jia; differences, but basically follows 1425 (no Xiao Hujia);

"Dong Tinglan" |

|

4. 風宣玄品

(1539; II/360) |

18T; Da Hujia; same as 1425 (also has XHJ)

No preface |

|

. 琴書大全

(1590; V/263-9) |

No music, but extensive commentary and three poems,

18 sections each, by Wenji herself, Liu Shang, and Wang Anshi |

|

5. 文會堂琴譜

(1596; VI/270) |

18T; HJ18P, but basically same as above

No commentary |

|

6. 綠綺新聲

(1597; VII/33 [details]) |

HJ18P; Cai Wenji lyrics;

fugu mode (but 7 strings)

Music completely different (attribution?); see comments above and elsewhere. |

|

7. 琴適

(1611; VIII/46) |

HJ18P (1st page missing); music and lyrics same as 1597;

Lyrics also placed at front of each section |

|

8. 理性元雅

(1618; VIII/331) |

HJ18P; lyrics; 9 string qin; no attribution

lyrics same as 1597, but melody again different |

|

9. 古音正宗

(1634; IX/378) |

Da Hujia; same as 1425

no commentary |

|

10. 澄鑒堂琴譜

(1689; XIV/342) |

Hujia; hints at 1425 on 1st line, then seems

almost completely different; no commentary;

This version became the standard one for the next two centuries |

|

11. 琴譜析微

(1692; XIII/132) |

HJ18P; almost same as 1689

No attribution |

|

12. 響山堂琴譜

(<1700?; XIV/122) |

Hujia; 18 sections related to 1689

No commentary |

|

13. 蓼懷堂琴譜

(1702; XIII/295) |

18 Pai; almost same as 1689

No attribution |

|

14. 五知齋琴譜

(1722; XIV/558) |

HJ18P; several recordings available (see

Wu Jinglue and this analysis); almost same as 1689;

Attrib. Cai Yan; her complete lyrics (source) are copied out after the tablature |

|

15. 臥雲樓琴譜

(1722; XV/125) |

HJ18P;

|

|

16. 存古堂琴譜

(1726; XV/296) |

HJ18P;

|

|

17. 琴書千古

(1738; XV/447) |

Hujia;

|

|

18. 春草堂琴譜

(1744; XVIII/280) |

Hujia

|

|

19. 蘭田館琴譜

(1755; XVI/286) |

HJ18P; compare 1689

(Sections sometimes divided differently) |

|

20. 琴香堂琴譜

(1760; XVII/177) |

HJ18P; like 1689

|

|

21. 研露樓琴譜

(1766; XVI/513) |

HJ18P; 18T

|

|

22. 自遠堂琴譜

(1802; XVII/480) |

Hujia; like 1689

|

|

23. 裛露軒琴譜

(>1802; XIX/110) |

Hujia; Preface; short comment with each section

"蜀譜吳派" |

|

24. 響雪山房琴譜

(>1802; XIX/418) |

HJ18P; short comment with each section

"前叙起指" |

|

25. 琴譜諧聲

(1820; XX/172) |

HJ18P; some sections have comments;

at end are comments about the tuning and melodies that use it |

|

26. 琴學軔端

(1828; XX/481) |

HJ18P;

XX/477 has Cai Wenji lyrics |

|

27. 二香琴譜

(1833; XXIII/174) |

HJ18P;

"緊五慢一;宮音" |

|

28. 悟雪山房琴譜

(1836; XXII/402) |

Hujia

|

|

29. 琴譜正律

(~1839; XXIII/62) |

Hujia

"太簇調,商角音" |

|

30. 稚雲琴譜

(1849; XXIII/409) |

18 Pai

|

|

31. 琴學尊聞

(1864; XXIV/257) |

HJ18P; "same as 1738"

|

|

31. 蕉庵琴譜

(1868; XXVI/89) |

HJ18P;

same commentary as 1722 |

|

32. 天聞閣琴譜

(1876; XXV/609) |

HJ18P; 16 Sections?

"= 1738" |

|

33. 天籟閣琴譜

(1876; XXI/214) |

Hujia

|

|

34. 響雪齋琴譜

(1876; ???) |

Hujia

Not in QQJC |

|

35. 希韶閣琴譜

(1878; XXVI/383) |

HJ18P; preface and afterword

Verse of Cai Wenji's poem placed after each section |

|

36. 枯木禪琴譜

(1893; XXVIII/113) |

Hujia; preface

Cai Wenji's poem at end |

|

37. 琴學初津

(1894; XXVIII/390) |

HJ18P; "仲呂變調宮音";

Cai Wenji poem at end |

|

38. 琴學叢書

(1910; XXX/331) |

HJ18P; from 1722

Also in 琴府 |

|

39. 虞山吳氏琴譜

(2001/216) |

Da Hujia; from 1425

|

Return to the top, to the Shen Qi Mi Pu ToC, or to the Guqin ToC.