|

T of C

Home |

My Work |

Hand- books |

Qin as Object |

Qin in Art |

Poetry / Song |

Hear, Watch |

Play Qin |

Analysis | History |

Ideo- logy |

Miscel- lanea |

More Info |

Personal | email me search me |

| Zheyin ToC Melody of the Fisherman's Song Standard tuning Yu Ge Yu Ge Scroll | 聽錄音 My recording/transcription / 首頁 |

|

09. Fisherman's Song ("Ao Ai")

- Ruibin mode,2 from standard tuning raise the 5th string: 2 3 5 6 1 2 3 |

漁歌 ("欸乃")

1

Yu Ge |

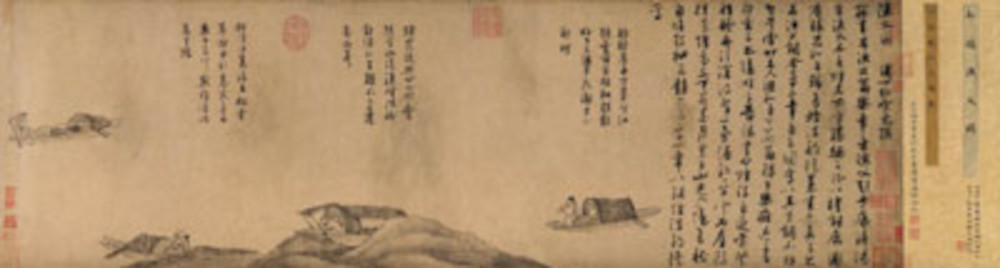

| From the Shanghai Museum: Wu Zhen, The Fisherman3 |

The earliest surviving version of the present melody (today more commonly called "Ao Ai" or "Ao Ai Ge", an onomatopoeic representation of sounds made by fishermen4) occurs in Zheyin Shizi Qinpu (<1505), where it follows the short song Yuge Diao (Fisherman's Song Melody). This Yuge Diao is a setting to music of a poem called Yu Weng (The Old Fisherman). Yu Weng is by the famous poet Liu Zongyuan (Liu Zihou, 773-819), and apparently for this reason the melody Yu Ge has also often been attributed to him.5

The earliest surviving version of the present melody (today more commonly called "Ao Ai" or "Ao Ai Ge", an onomatopoeic representation of sounds made by fishermen4) occurs in Zheyin Shizi Qinpu (<1505), where it follows the short song Yuge Diao (Fisherman's Song Melody). This Yuge Diao is a setting to music of a poem called Yu Weng (The Old Fisherman). Yu Weng is by the famous poet Liu Zongyuan (Liu Zihou, 773-819), and apparently for this reason the melody Yu Ge has also often been attributed to him.5

In fact, though, there are two very different Fisherman's Songs that seem to have grown up together:

Both versions remain in the current repertoire, the standard tuning one still called Yu Ge. There are over 30 published versions of each,6 with most having 18 sections.7

In addition, there are also many recordings of the standard tuning Yu Ge (for example there are 10 listed here) as well as of the raised fifth Yu Ge now called Ai Nai (though just 2 of these are listed here). Within each tuning all melodies are clearly related, though there are also very significant differences.8

Both the Yu Ge (Ao Ai) using ruibin tuning and the Yu Ge using standard tuning survive in about 35 handbooks, the former from >1505 to 1876, the latter from 1525 to 1910. The earliest handbook with the standard tuning Yu Ge, Xilutang Qintong

Commentary on Ao Ai Ge in at least two handbooks, Chuncaotang Qinpu (1744) and Erxiang Qinpu (1833), begins by saying that it is commonly called the "northern Yu Ge"; the writers then suggest this is a mistake, Erxiang Qinpu explaining that Ao Ai is pentatonic (5 tone scale) and Yu Ge is diatonic (7 tone scale).10 This is not actually true of these two versions, but several other factors also suggest that the ruibin tuning Yu Ge should be considered a southern counterpart to the standard tuning northern one. Section titles and lyrics of the present ruibin version associate it with the south (Chu), whereas the Xilutang Qintong standard tuning version has section titles with associations to the region around Jiangsu's Lake Taihu. In addition, other melodies with one of the raised fifth tunings are often associated with Hunan and the ancient kingdom of Chu.11 And Liu Zongyuan spent years of exile in Hunan.12

My recording of the Yu Ge in Zheyin Shizi Qinpu shows some rather exotic modality in the second part of Section 14, following a comment that says these are "oar sounds".13 First there is a passage which has the repeated sequences 1 3 4 3 4 6 4 3, very much like a Japanese scale. The phrase ends on repeated intervals of a diminished ninth chord (3 and 4) and the following phrase then ends with a strong cadence on another diminished ninth (6 and 7 flat). I interpret the flatted 7 as leading strongly into the next passage, which begins on 6 (the tonic).

As mentioned in Tuning the Qin, early qin music includes quite a few passages which don't fit into the modality expected today. This is perhaps the most idiosyncratic passage. At first when I encountered it I was quite convinced there was a mistake (the sample page shows some actual mistakes from that page), and I tried to get myself to "correct" it; but the more I tried, the more I kept coming back to these fanciful dissonances. For me they work.

Zheyin groups this with the preceding piece,

Yuge Diao, and so it has no

separate preface.14

00.00 1. Clouds over the Xiao and Xiang rivers

Return to the Zheyin Shizi Qinpu index

or to the Guqin ToC.

1.

Yu Ge 漁歌 (QQJC I/218)

2.

Ruibin mode 蕤賓調

In preparation: note counts.

3.

Wu Zhen (1280-1354): The Fisherman 吳鎮,漁父圖

Zheyin Shizi Qinpu preface

Music15

Timings follow the recording on

my CD;

聽錄音 listen with

my revised transcription

(pdf; combined with Yu Ge Diao; compare original).

18 Sections, titled; lyrics throughout (they are

translated below but have not yet actually been sung).

See also my video recording with the new transcription (links there also to my video of the

sung prelude).

This illustrated Yu Ge Scroll has 18 images but they are connected to the standard tuning Yu Ge.

01.08 2. The autumn river shines like a ribbon of white silk cloth

01.51 3. Autumn thoughts by Dongting lake (in harmomics)

02.16 4. Mist and waves on the Chu and Xiang

02.54 5. A brilliant moon in the broad firmament

03.30 6. The fishermen's songs echo back and forth

04.29 7. Wild geese call "yan yan"

05.01 8. An evening alongside the western cliffs

05.27 9. The fishermen sing in the evening

06.23 10. Drunkenly lying among the rushes (in harmomics)

07.07 11. Evening rain on an overgrown lattice window

07.33 12. Leaves fall from the wutong tree

08.00 13. At dawn drawing water from the Xiang river (first half in harmomics)

08.30 14. The fishermen in boats row their oars

09.04 15. Casting a net into the cool river

09.45 16. The sun comes out, dissolving the mists

10.12 17. The sound "ao ai" (oars splashing)

10.29 18. High mountains and long rivers.

10.49 Closing harmonics

11.02 End

Footnotes (Shorthand references are explained on a

separate page)

18588.87 "song sung by a fisherman"; 18589.88 漁歌子,Yu Gezi 詞牌名 name of a ci song poem pattern connected to a poem by Tang poet 張志和 Zhang Zhihe (730-782).

(Return)

1=do, 2=re, etc.; in my transcription do is written as c, but the exact pitch depends on such things as the size and quality of the instrument and strings. For more information about 蕤賓調 ruibin mode see

Shenpin Ruibin Yi. For modes in general see Modality in Early Ming Qin Tablature.

(Return)

At top is an excerpt from the Shanghai Museum website of this scroll painting; the full scroll is in the Shanghai Museum but a full version seems no longer to be online there.

|

(Return)

4.

The title "Ao Ai" or "Ai Nai" instead of "Yu Ge"

These syllables perhaps represent a fisherman's call rather than song, though perhaps fishermen would call out these words in a songlike manner. References include:

- 16442.0 欸 gives ai, i and ao as pronunciations for several types of interjections.

- 115.0 乃 gives both nai and ai as pronunciations, associating the latter with 欸乃.

- 16442.1 欸乃 can thus be pronounced Ao Ai, Ai Ai or I Ai, though it is now also commonly pronounced Ai Nai. It is defined as "棹(zhao)船相應聲,又揺櫓聲。轉用為船歌、漁歌 sounds corresponding to those of rowing a boat, and also the sounds of swaying oars; especially used for boat songs and fishermen's songs".

- 16442.2 欸乃曲 Ao Ai Qu gives several references and says it is also a 詞牌名 poetic rhythm. 16442.3 欸乃詞 Ao Ai Ci is a woodcutter's song.

I have not heard sound samples of these syllables being called out.

(Return)

5.

Liu Zongyuan, the Old Fisherman 柳宗元,漁翁

Liu Zongyuan was also called 柳子厚 Liu Zihou. Melodic settings of his poem, which survive in 12 handbooks up to Meian Qinpu (1931), are discussed under Yu Ge Diao. Xu Jian,

Qinshi Chubian, p.75 discusses the connection between Yu Ge Diao and Ao Ai. Some handbooks also attribute Ao Ai itself to Liu, while some later ones even attribute to him the zhi mode Yu Ge.

(Return)

6.

Tracing Yu Ge and Ao Ai

For details see appendix below. For printed and punctuated copies of prefaces, etc., see Zha 11/117/200 (Yu Ge) and 21/190/376 (Ao Ai). Zha generally puts all the Yu Ge together, even if they use

ruibin tuning.

(Return)

7.

Most have 18 Sections

The main exception is a 10 section standard tuning Yu Ge noted as following the Meixuewo revision.

(Return)

8.

Transcriptions and recordings (other than my own)

Transcriptions of Yu Ge in the old Guqin Quji are all of one of the standard tuning versions. These are listed under the

standard tuning version introduction.

As for transcriptions and recordings of the raised fifth tuning version of Yu Ge (later called Ao Ai), most easily available is the 節本 abridged version that is #6 in Level 8 of the conservatory repertoire Guqin Quji (see below). Almost all the current Ao Ai recordings are based on this or another abridged version.

As for a full length recording and/or transcription of Ao Ai, there seems to be only one (other than my own), and that is the one by Guan Pinghu based (somewhat loosely) on the 18 section version dated 1876. It can be heard on his CD 2, track 8, but there is also an mp3 copy here. There is also a transcription into number notation said to have been 河東張心遠記譜、螫理 written down and organized by Zhang Xinyuan of Hedong (for a book called 平湖秘譜 Personal Tablature of Pinghu). Based on this transcription, which can be seen here, the basic scale is 1 2 3 5 6, with 6 as the tonal center and virtually all the non-pentatonic notes being 7s going down to 6. I have not studied other late versions enough to know whether Guan himself "corrected" many of the notes (there was a common view that qin music should be pentatonic and there had long been a general trend in that direction). In any case this gives the modern version a very different feel from the earlier one.

Guan's recording follows the 1876 version section by section but not note for note; timings are:

- 00.00 (related to the preludes such as Leji Yin that succeeded Yu Ge Diao)

- 01.01 (main melody of early versions begins)

- 02.31

- 03.42 (harmonics)

- 04.01

- 04.38 ("slow")

- 05.10

- 05.40

- 06.32

- 07.05

- 07.44 (harmonics)

- 08.00

- 08.35

- 09.19 (harmonics)

- 09.35 (includes comment "如䜭[浚]次第車上")

- 10.00

- 10.35

- 11.29 (quite slow)

Coda: 12.14 (harmonics; end 12.30)

In the earliest version (see track 9 of my CD) the harmonic sections are #s 3, 10, 13 and the coda. One can see connections in the tablature between that version and this one, but they are difficult to hear.

The relationship between conservatory abridged version and the one played by Sun Yü-Ch'in is not clear. There were a number of abridged versions made, apparently in the 1980s and '90s, and recorded; it seems that no one else wanted to play the full version. The conservatory version is said to have been abridged by Li Xiangting, but it does not seem much different from these earlier abridged versions.

(Return)

9.

Ao Ai and

Yu Ge in

Xilutang Qintong (1525)

Ao Ai is the 112th melody in Xilutang Qintong, compiled by Wang Zhi (王芝), who lived on the southeast side of Huang Shan mountain in Anhui province. Wang in the introduction of his handbook says he spent 30 years collecting the tunes. Some of these seem to be very early versions, some quite late. His Ao Ai is quite different melodically from the earlier raised fifth Yu Ge. In addition, the titles of the 16 sections are also quite different from those for Yu Ge in Zheyin Shizi Qinpu.

The preface for Ao Ai in Xilutang Qintong as follows,

The standard tuning Yu Ge is the 82nd piece in Xilutang Qintong. For it Xilutang Qintong has the following preface,

10.

Northern and Southern Songs of the Fisherman

11.

Chu connection to raised 5th tunings?

12.

Location of Dongting

13.

Section 14: "Oar sounds" (櫓聲 lu sheng)

In the referenced first passage from >1505 (1 3 4 3 4 6 4 3), the "1" is actually written in a position producing 7 , but the fingering required for this followed by that for 3 is very awkward.

14.

Original preface

15.

Music and lyrics with tentative translation (QQJC I/218-222)

Xiao Xiang Water and Clouds

Autumn River Like Silk

Autumn Thoughts at Dongting Lake (in harmonics)

Mist and Waves of Chu and Xiang

Vast and Clear Skies

Fishermen’s Songs in Response

The Cry of Wild Geese

Night by the Western Cliff

Fisherman’s Evening Song

Drunkenly Lying amidst the Reed Blossoms

Night Rain on a Reed-Covered Window

Fallen Leaves of the Wutong Tree

Morning on the Xiang River (in harmonics)

Oars on the Fisherman’s Boat

On a Cold River Casting Nets

Sunrise and Mist Disperses

"Ao Ai": The Call of the Fisherman

(Coda (in harmonics))

(See again the note on translation above; as best as possible, both the Chinese and the English text is arranged line by line with the

revised transcription.)

Gloss of proper names occurring in the lyrics:

(Return)

Chuncaotang Qinpu (1744) and

Erxiang Qinpu (1833) both have statements about the raised fifth version of Yu Ge being incorrectly called "northern Yu Ge". 1744 says this is wrong and it does not know where the idea came from. 1833 seems to give some explanation. After saying that Ao Ai Ge is commonly called "northern Yu Ge" it first says that old handbooks such as

1589, 1596 and 1611 call it Yu Ge and that their harmonic closings end either with the sounds of the 3rd and 5th strings (so do; see 1589, 1596 [but note, e.g., that >1505 ends on la; 1539 and

1579 end on mi la) or on the first and sixth strings (mi mi; 1611 [as do 1525, 1552]). "These are other melodies. Later, 1689 closed with the second and fourth strings (mi la): this is a yu melody" (羽 yu is la). Moreover, the northern "一字" (do) is not seen (as an ending) in printed versions. The so-called 'northern Yu Ges' are different from the Yu Ges that are 正調商音 zheng diao shang yin (standard tuning)." It goes on to say that in China, northern music tends more towards being diatonic than does southern music, and that it wants to distinguish the two melodies by referring to the raised fifth tuning one as Ao Ai because of the

line in the poem by

Liu (Zongyuan). It may be that later versions of Yu Ge were more diatonic (using seven tone scale) and of Ao Ai were more pentatonic, but this is not evident in the earliest surviving editions. See also the footnote with the standard tuning Yu Ge.

(Return)

There is no information explaining this apparent connection, nor any evidence that ancient Chu melodies had this characteristic.

(Return)

The situation is made more confusing by there being a 洞庭 Dongting (an island, hill or cave) in Taihu as well as the more famous Dongting Lake in Hunan. There is a relationship between the section titles of the ruibin Yu Ge and those of Xiao Xiang Shui Yun, which also uses ruibin tuning. And several prefaces to later versions of Zui Yu Chang Wan suggest it has melodic relations to (the zhi mode version of) Yu Ge.

(Return)

Another possible example of an apparent dissonance resolving to a tonal center seems to occur in Moufu Kuang Jun. For another depiction of "sounds" compare also the passage in Qiu Hong Section 16, said to be the sound of geese calling to the moon. In most versions of Ao Ai beginning with ca. 1700 this seems to corresponds with the concept of Section 15, this section also sometimes being singled out for comment (see in chart beginning with 1726), but the music is very different. In the modern abridged version that passage from Section 15 may have some connection to material in what is #6 in Level 8 of the

conservatory version (Vol 2, p.81).

(Return)

See the Yuge Diao Preface

(Chinese). In later handbooks, commentary with this ruibin tuning Yu Ge, as with Ao Ai, often associates the melody with Liu Zongyuan, as here.

(Return)

The original Chinese lyrics are as follows (the original preface and section titles can be seen under 漁歌). The lyrics are paired to the music following a largely syllabic formula, but there is no existing commentary on how or even whether they were ever actually sung. Although the punctuation here largely follows that in this .pdf file (from Zha Guide 200 [724]), the line by line arrangement below follows the phrasing of my musical interpretation as reflected by my revised transcription. This, in turn, generally but not completely follows the rhyme scheme. Repeated punctuation marks such as , , mean that there were instructions for the previous musical phrase to be repeated; it is not clear whether it was intended that the lyrics also be repeated.

(Note added 30 December 2024: As discussed here, silkqin.com got started so that I could document my reconstruction work in a way that allowed me easily to search what I had done. This is one reason why there is quite a bit of Chinese on the site that has not been translated - it awaits translation when I have the time and knowledge to do it properly. I originally put the following lyrics for Yu Ge here only in Chinese to better remind me of the general meaning of what I was reconstructing and then playing. Now here for the first time I am using ChatGPT to help with translation: it does an amazing job with classical Chinese but can also make bad mistakes so must be thoroughly checked. This has led to some revisions in my musical interpretation and also hopefully will help convey to others something of relationwhip between the music and these lyrics.)

家住吳楚大江頭,浪花中一葉扁舟。

輕畫槳,南北遨遊,無累的那亦無憂。

老天有意難留,去年今日蘭江渡口。

今日湘浦也巴丘,任消愁。

有那箇青箬笠,綠蓑衣,碧沙紅蓼白蘋洲。

絲綸短放却長收,忘機也友愛鳧鷗。

日月悠悠,水雲浮浮,湘江湘江兩岸秋。

畫橋綠水也通天流。落霞孤鶩。

宿兩方初收。睡齁齁,夢悠悠,遠迷蝴蝶到莊周。

Dwelling near the top of the great river where Wu and Chu meet, on a lone leaf-like boat amid the waves’ froth.

Lightly rowing, wandering north and south, unburdened and carefree.

Heaven suggests it is hard to stay in one place: last year on this day I was at a

Lan River crossing,

Now today I am on the banks of the Xiang in Baqiu, allowing my sorrows to dissipate.

Having a blue bamboo hat and green raincoat, midst emerald sands, red smartweed and white duckweed isles.

Fishing line cast short, yet retracted long, unmindfully befriending wild ducks and gulls.

Days and months drift by, water and clouds float on, autumn on both banks of the Xiang River.

Painted bridges, green waters flowing to the sky,

setting sun and solitary birds.

I rest as dusk settles in, then sleep soundly, dreaming endlessly, as

far-off butterflies lost to Zhuang Zhou

(see Zhuangzhou Meng Die).

一天秋,那粧點出 那鑑湖光,耽那風月駕舟航。

如油澄淸綠水,帶連彭蠡,近接着荊湘, 。

愛那蓴鱸江,好風涼,紅塵世累總相忘,

煙水也白茫茫。棹破江心浪,扁舟蕩漾。

明明皓,月浸銀潢,綸竿高舞影,鈎餌細分香。

渭水功名周呂望,富春山漢嚴光。

On a day in autumn, nature's adornment brings out the reflective light of the lake, luring the wind and moon as the boat sails.

Crystal-clear green waters reflect like oil, seeming to connect

Pengli with Jingxiang.

I adore the reeds and fish in this river’s breeze, forgetting the dust of the world entirely.

The misty waters stretch white and vast, my oar stirs the river’s waves, rocking my small boat as it drifts along.

Under the bright moon, silver light washes the Milky Way,

my fishing rod dances high, with alluring fragrance on its hook.

(This is like) on the Wei River fame gained by Lü Wang of Zhou, and at Fuchun Mountain by Yan Guang.

海天萬頃波光浮,氷壺玉宇澄淸秋。

自自在在中流,不繫扁舟。風與露任蕭條,接長綸線。

直卻那金鈎,想他無心,皆漢有意匡周。

世事無憑,功名兩字,一似浮漚。

With the sea and sky vast and boundless, light sparkles off the waves,

icy pots and jade vessels have the clarity of autumn.

In mid-stream, untethered boats drift,

and as wind and dew embrace the desolation, fishing lines extend far.

Straightening out the golden hooks, and thinking of them without worry, yet Han still hoped to aid Zhou.

However, worldly affairs are fleeting illusions,

and fame is but a word, just like bubbles on the water.

漁歌悠悠,楚水湘波,煙藹藹,宿雨初過。

見風帆的那賈客怕,來往爭逐去如梭。

誰如漁夫漁婦,暢此中流,慢枻輕歌。無榮無辱,無福無禍?

儒也無過,道也無過,儒釋道總無過。

百家衆技 總總無過,權謀術數

遠更無過,無過,無過。

The fisherman’s song is drawn out, over the waters of Chu and ripples on the Xiang.

Smoke rises faintly, the rain has just passed.

Merchant ships are swift and restless, racing back and forth like weaving shuttles.

Yet who can compare to a fisherman and his wife: drifting midstream, paddling slowly and singing lightly;

no honor, no disgrace; no fortune but also no faults?

To Confucians this is faultless; to Daoists this is faultless; Confucians, Buddhists and Daoists all find this faultless.

The thinkers of 100 schools, they also find this faultless. So when it comes to strategies and skills of intrigue,

(Fishing people) are even further from having that fault, no fault, no fault at all.

天磨雲影,好風那寂靜,

皓月明明,玉露泠泠。

輸彼漁翁,鼓枻輕輕。

天淸地寧,長笑一聲。一目中,

舒義氣浩浩,小呑那巴蜀,

空澗那洞庭,漁歌有狀無形。

托他一箇討魚名,投閑養性怡情。

The sky polishes clouds into shadows, gentle breezes whisper in stillness.

The bright moon gleams, the jade dew chills.

As the fisherman moves along, he paddles gently, gently.

Heaven clear, earth serene; laughter echoing wide and free. In his gaze:

He extends noble thoughts vast and grand, savoring all of Ba and Shu (Sichuan).

in the vast emptiness over Dongting, the fishermen's songs though formed are beyond form.

Under the guise of their trade, they retreat into peace and joy.

問彼漁郞,風波險處舟航?

濤浪相舂撞,相舂撞,

思量怎的去隄防?

那漁郞抵掌,嘻嘻向我 行言其當。

死生也有定,由天命。

知我背,,卻無方。欸乃歌,和聲長,

山隱映,那水微茫。纔聽大郞歌,

又聽小郞相倡和,淸濁的那和滄浪。

聲隨流水,轉壑悠揚,

濯纓濯纓,濯足濯足, 和滄浪。

響過你那行雲天蕩蕩,

翩翩鷗鷺,驚起寒沙亂飛張。

扁舟落日動鳴榔,魚吹浪,天昏黃。

A question to the fisherman: in dangerous waters and storms how do you navigate a boat?

Waves are crashing together, tumbling violently,

How do you reach the embankment and find shelter?

The fisherman claps his hands, his laughing to me suggests this is just the way it is.

“Life and death are preordained, this is by heaven’s decree.""

Knowing this I turn away, it seems there is no way out.

The "ai nai" of fishermen's songs echos long.

Mountains hidden, waters faintly blurred, and now an elder is singing.

Hearing this a younger one joins in, clear and turbid sounds merge with waves (canglang),

The melody flows like the waters (liu shui), echoing gently through valleys.

Washing the ribbons (in our hats), washing the ribbons; washing the feet, washing the feet, as in the Canglang.

Sounds extend beyond the drifting clouds and a sky so vast.

Arousing gulls and heros, startled by the cold sands they flutter chaotically.

As a boat in the setting sun moves a gong is stricken, fish "blow" (and their movement causes) ripples, and dusk deepens to a golden haze.

蘋洲蘆岸蓼汀,漁驚那鴻鴈鳴,

聽嗈嗈聲度那淒淸。

漁翁鴻鴈也,

兩相友愛,爲弟爲兄,

念群弔影忘形,弔影忘形。

欸乃的那聲相應,

聽嗈嗈和聲相應,相應,相應。

On reed-filled shores and grassy islets, fish are startled and geese cry mournfully,

Their call resounds in melancholy tones, both fishermen and geese.

As brothers, they have camaraderie, they console shadows, forgetting forms,

With their plaintive songs in harmony, they listen to the blending echoes, resonating.

Resonating, resonating.

漁翁夜傍你那西巖宿, 。

酒醒無眠也和歌曲。

漏深歌轉兮。

聲斷續,好夢呵從吉卜。

紅日呵三竿足。

睡也那不足,樂也那不足。 ,。

The fisherman moors nightly by the western cliff, .

Awake from drink, sleepless, he hums a tune; deep into the night the singing drifts along.

Sounds both brief and long, good dreams following the rhythm of fate,

and at dawn a red sun rising high and its mid-day, ("three poles high")

Yet he feels the night’s joy insufficient, and laughter’s warmth incomplete; , .

出桃花灘,離芳草渡。

過蘆花洲,繫楊柳埠。

聽漁歌,,夫唱婦相助,氣應聲相互。

落日西斜,長天欲暮,

月照蘆花,的那無寐還無寤。

江天煙雨,黃昏綠樹,今夜也,

不知在那何處住。十里長灘,

接着那野墅。聲逐西風,的那

悠揚遠度,離愁如訴,會合無憑如訴,成歡成怒。

遙想你那風月,長春院,古樂府。

吹也,唱也。響遏繞

梁聲,何足數,何足數。

Coming from Peach Blossom Ford, leaving at Fragrant Grass Crossing,

Passing Reed Flower Islet, mooring at Willow Dock (I don't know if any of these is a proper name).

Listen to the fishermen’s songs,,

husbands and wives singing in unison, voices blending harmoniously.

The setting sun tilts westward, the sky grows dim,

The moon shines on reed flowers, (but for me) there is neither being asleep nor wake.

River and sky have mist and rain, at dusk the trees are still green; as for tonight:

Who knows where I’ll rest? The 10-li long beaches?

Or alongside countryside cottages?

Sounds drift far with the western wind,

Eloquent and floating away, when parting sorrow tells the tale, when re-uniting a lack of evidence tells the tell; this turns joy into anger.

From a distance thinking back on the wind and moon, the Long Spring Courtyard, the ancient music halls.

Blow! Sing! The sound will resonate and entwine.

As for sound from the beams, how could that be counted? How could that be counted?

漁翁得魚沽酒斜陽城,

漁翁力拳沽酒輸還贏。

醒還醉,醉還醒,蘆花月明,

悠悠楊柳風淸,高枕外,有餘情。

長呼吼,魚龍驚,更深夢寐(泛音止)無成。

看他無拘無束,放浪、放浪一身輕,

向那閑中臥,老此昇平。

The fisherman catches fish and buys wine at twilight inside the town,

That fisherman uses all his strength to buy win, alternatively failing or succeeding.

Awake to drunkenness, and drunk to wakefulness, under the moonlit reeds,

The gentle breeze through the willows is clear; resting high on a pillow he harbors lingering thoughts.

Long cries, fish and dragons are startled, There are deeper dreams, and nothing is achieved.

Deeper into the night, dreams pass uneventful.

Look how he is carefree and unrestrained, living freely, living freely and light in body.

Reclining in leisure, glowing old in a peaceful life.

雨聲不息,一更不息,二更不息,三更

不息,四更不息,五更點點滴滴。 蓬窓內,

兒與媳,蘆花毯,無愁濕,好良宵,雖愛惜。

水國兮,江鄉兮,風浪屏蹤跡。

三唱雞聲天又白,尚愁天色。

The rain sound never stops, through the first watch it doesn't stop, through the second watch it doesn't stop, through the third

it doesn't stop, through the fourth it doesn't stop, Until the fifth it drops softly and continuously. Within the thatch-covered window,

A child and a daughter-in-law with a reed mat, untroubled by dampness, a good night though precious,

Is a watery land, this river-bound village, wind and waves hide their tracks.

With the third crowing of the rooster, dawn breaks; yet we still worry about the color of the sky.

金井梧桐葉飄,風颼颼,涼瀟瀟,

任彼那漁舟樂得逍遙。 。

月光浮,夜迢迢,寂寥。 ,,。

敲直釣魚釣,煙水海天秋,抱着那七絃琴。

悠悠輕奏,秋風調,怡情風月江頭。

Leaves from a wutong tree by the golden well dance. The wind whispers, cool and refreshing.

Let that fishing boat enjoy its leisurely joy. .

Moonlight drifts, the night stretches far, lonely and desolate. , , .

Striking the fish with a straight rod, misty waters under the autumn sky;

embracing a seven string qin."

Gently and leisurely play the autumn wind piece, savoring the wind and moon by the river’s edge.

輞川鷗鷺齊飛,吳江鱸鱖齊肥,

湘江汲炊行竈。曉煙浮,

楊柳糢糊抹翠,細劈江東(泛音止)魚鱠,

醉飽陶陶穩睡。蘆荻灘頭, ?,

舟橫的那網曬綸收,逍遙物外。

By the Wangchuan (see Wang Wei) gulls and herons fly together; the Wu River is filled with fat bass and perch.

On the Xiang River water is drawn, meals prepared, and morning mist hovers faintly.

Willow branches blur into smudges of green, and fish from east of the river (harmonics end) are finely sliced.

Sated with drink and food, he sleeps soundly, by the reed-filled shoals,

The boat steadied, nets dry, lines are gathered, carefree and detached from worldly affairs.

咿啞咿啞的那櫓聲。

和煙輕,撥進趨前程。

江天空濶浪初平,

(櫓聲)遙看盪漿行歌慢和 輕,深撥棹,作揖而行。

月白風淸,高竿又向柳陰撐,

忙驚散鷗鳥盟,遙思今夜宿江城。

Yi-ya yi-ya the oars creak softly,

The sound mingles with light mist, pushing the boat steadily forward.

The river opens wide, waves calm and smooth.

(Sound of the oars) From afar, they row and sing, slowly harmonizing.

Oars dip deeper, bowing gracefully in their rhythm.

By the moonlight, a tall pole pushes off the willow’s shade,

Scattering startled gulls, thinking of tonight’s mooring in the riverside town,

江岸寒風輕刮,霜凜冽,看漁人。

舉網輕撒,發撒。扎撒,網收魚潑剌,

槳催呵逐步孳,從前軋。

斷續也聲咿啞,兩手輕輕的那提挈,

水底輕撈月, 。

風中輕捉雪, 。

網收,網撒,魚鱖呵潑剌。

網收呵,網撒。

Cold winds brush against the riverbank, frost chills the air, and look at the fisherman:

He throws his net lightly — out it goes! Quickly gathering, the net pulls in fish with much splashing.

The oars creak as they push onward, pausing briefly, then rolling on.

The intermittent oar sound "yi-ya" is soft, as with two hands he gently guides (the net) upward.

It is as if from beneath the waves he is scooping moonlight,

Or in the wind lightly catching snowflakes.

Net retrieving, net casting, fish thrashing and splashing with a flourish.

Retrieving, ah, and casting.

黑甜夢醒時你那紅日曉,晴天四野煙消, 。

從他網踈網密,無與有,任敎漏卻呑舟。

恣遨遊,萍蹤梗跡,的那亂飄飄,浪花浮,

只托個打魚名的那,去爲由。

Awakened from a deep dream as the red sun rises at dawn, skies are clearing and mist lifting, .

From him comes whether the net is loose or the net tight, whether there is existence or non-existence, and even whether if the net leaks it can swallow a boat whole.

Freely wandering, drifting along like duckweed, like tangled reeds, tossed in the waves, afloat on spray and foam.

He claims "fisherman" in name only, it is just a pretext for going and staying.

那釣魚人原是靑雲客,

人不識。罷絲綸,懶去釣王國,

怕遭遇你那周西伯。

The fisherman was once someone who cast for clouds,

No one knew of him. He abandoned his fishing line, but only lazily went casting for worldly kingdoms.

He feared encountering another Zhou Xibo.

山髙水長,輸他笑傲徜徉。

屏屠龍手段,托個討魚的名,

林泉晦跡韜光。

坎止流行意趣,隨所寓。

When snags block the mind's free flow, adapt to the environment.

巴丘 Baqiu: Yueyang area; Qu Yuan also wandered here, met fisherman and drowned

荊湘 Jing and Xiang: Jing is an ancient name for Chu as well as a district (Jingzhou) in western Hunan; together these suggest watery regions of Chu

(Return)

Appendix: Chart Tracing Standard and Raised Fifth Ao Ai / Yu Ge

Based mainly on Zha Fuxi's Guide,

11/117/200 Yu Ge and 21/190/376 Ao Ai

See also the Yu Ge Diao chart

|

琴譜

(year; QQJC Vol/page) |

Further information (QQJC = 琴曲集成

Qinqu Jicheng; QF = 琴府

Qin Fu)

Raised fifth tuning - Not clear - Standard Tuning |

|

1. 浙音釋字琴譜

(>1505; I/217) |

18TL; ruibin diao (RBD); first version of melody later called Ao Ai

Yu Ge; "by Liu Zihou" (Liu Zongyuan), preceded by Yu Ge Diao, with which it shares a preface |

|

2a. 西麓堂琴統

(1525; III/206) |

16T; RBD; section titles different; melody also very different: e.g., opens with harmonics

Ao Ai (very different, though parts are clearly related) |

|

2b. 西麓堂琴統

(1525; III/165) |

18; zhi diao (ZD; has

prelude)

I play this version; afterword mentions Mao Minzhong; Yu Ge |

|

3. 風宣玄品

(1539; II/342) |

18T; RBD; similar music to >1505, with same section titles but no lyrics

Yu Ge (no Yu Ge Diao) |

|

4. 梧岡琴譜

(1546; I/436) |

10; 徵調 zhidiao (ZD); no commentary

Meixuewo edition, 即山水綠 same as Shanshui Lü"; Yu Ge |

|

5. 琴譜正傳

(1561; II/509) |

10; ZD; identical to 1546

Meixuewo edition, "即山水綠 same as Shanshui Lü"; Yu Ge |

|

6a. 太音傳習

(1552-61; IV/180) |

18; RBD

Ao Ai Ge; preceded by Leji Yin; preface mentions 山水綠之詩 poem of Shanshui Lü |

|

6b. 太音傳習

(1552-61; IV/126) |

12; ZD

Yu Ge; has preface |

|

7a. 太音補遺

(1557; III/399) |

18; RBD

Ao Ai Ge; preceded by Leji Yin; preface mentions 山水綠之詩 poem of Shanshui Lü |

|

7b. 太音補遺

(1557; III/371) |

10; ZD

Yu Ge; preface like 1552 |

|

8. 步虛僊琴譜

(1556; III/286) |

11; ZD

Yu Ge |

|

9. 五音琴譜

(1579; IV/247) |

18; RBD (listed under wai diao)

Ao Ai Ge; no commentary |

|

10. 新刊正文對音捷要

(1573; #61--) |

#61; same as 1585?

Yu Ge; preceded by Yu Ge Diao |

|

11. 重修真傳琴譜

(1585; IV/472) |

18L; RBD; attrib. Liu Zihou; lyrics similar to >1505 but melody quite diff.;

Yu Ge; preceded by Yu Ge Diao |

|

12. 玉梧琴譜

(1589; VI/77) |

18; RBD

Ao Ai Ge; attrib. Liu Zihou |

|

13a. 真傳正宗琴譜

(1589; VII/138) |

18TL

Yu Ge; preceded by Leji Yin |

|

13b. 真傳正宗琴譜

(1609; facsimile) |

Repeat of 1589?

Yu Ge; preceded by Leji Yin |

|

14. 琴書大全

(1590; V/524) |

18; RBD; preceded by 神品蕤賓意 Shenpin Ruibin Yi (SPRBY)

Yu Ge; the SPRBY somewhat resembles the Yu Ge Diao melody |

|

15. 文會堂琴譜

(1596; VI/265) |

18; RBD

Yu Ge, "also called Ao Ai Ge" |

|

16. 綠綺新聲

(1597; VII/40) |

20L; RBD

Ao Ai Ge |

|

17a. 藏春塢琴譜

(1602; VI/430) |

18; RBD;

Ao Ai Ge; attrib. Liu Zihou, but no lyrics |

|

17b. 藏春塢琴譜

(1602; VI/385) |

13; ZD; commentary says only "古曲 old melody"

Yu Ge |

|

18. 陽春堂琴譜

(1611; VII/430) |

18; RBD; no commentary

Yu Ge; preceded by Leji Yin (Yu Ge Diao) |

|

19. 琴適

(1611; VIII/39) |

20L; RBD; lyrics are related, but very diff.; no commentary

Ao Ai |

|

20. 松絃館琴譜

(1614; VIII/129) |

18; zhi (diao); no commentary

Yu Ge |

|

21. 思齊堂琴譜

(1620; IX/51) |

18; 徵意 zhi yi; no commentary

Yu Ge |

|

22. 太音希聲

(1625; IX/223) |

18L; RBD

Ao Ai Ge |

|

23a. 徽言秘旨

(1647; X/222) |

18; RBD

Ao Ai Ge |

|

23b. 徽言秘旨

(1647; X/150) |

18; ZD

Yu Ge |

|

24a. 徽言秘旨訂

(1692; facsimile) |

18; RBD

Ao Ai Ge; should be same as 1647 |

|

24b. 徽言秘旨訂

(1692; facsimile) |

18; ZD

Yu Ge; should be same as 1647 |

|

25. 友聲社琴譜

(early Qing; XI/150) |

18; zhi (diao); 嚴譜 Yan tablature; no other commentary

Yu Ge |

|

26. 愧菴琴譜

(1660; XI/46) |

18; ZD

Yu Ge |

|

27. 琴苑新傳全編

(1670; XI/436) |

8; RBD; attrib. Liu Zihou

Yu Ge |

|

28. 響山堂琴譜

(<1700?; XIV/134) |

18; RBD; Section 2 is like Section 1 of earlier versions

Ao Ai Ge; earliest pu where Section 1 is like Leji Yin or a modal prelude |

|

29a. 澄鑒堂琴譜

(1689; XIV/333) |

18; RBD; seems identical to <1700

Ao Ai Ge |

|

29b. 澄鑒堂琴譜

(1689; XIV/252) |

18; ZD

Yu Ge |

|

30a. 蓼懷堂琴譜

(1702; XIII/???) |

1876 Ao Ai Ge says it is copied from here, but there is no pu and it is not in ToC

Presumably would also be Ao Ai Ge |

|

30b. 蓼懷堂琴譜

(1702; XIII/243) |

No lyrics or commentary; 18; ZD

Yu Ge |

|

31a. 五知齋琴譜

(1722; XIV/488) |

18; ZD; "熟、金二譜合壁,歌文錄未 compared Shu and Jin tablature; put lyrics at end"

Wu Zhaoji notation: GQQJ#1/104; Yu Ge |

|

31b. 五知齋琴譜

(1722; XIV/493) |

Lyrics of Leji Yin and a long Yu Ge Ci: no music (placed directly after standard tuning Yu Ge - see previous row)

(No tablature in 1722 for the ruibin versions!) |

|

32. 存古堂琴譜

(1726; XV/289) |

18; RBD (#15: "此段撥刺宜輕肥")

Ao Ai Ge; like <1700 |

|

33a. 春草堂琴譜

(1744; XVIII/275) |

18; 無射均,羽音 wuyi jun, yuyin; afterword: "一派南音,並無北韻。俗呼為'北漁歌',不知何指"

Ao Ai; like <1700; "completely southern sound, don't know why called 'Northern Yu Ge'" |

|

33b. 春草堂琴譜

(1744; XVIII/257) |

14; 中呂均 zhonglü yun (ZLY), 商音 shang yin (SY)

see afterword ("originally 18 sections...."}; Yu Ge |

|

34. 蘭田館琴譜

(1755; XVI/237) |

18; ZD

Yu Ge |

|

35a. 琴香堂琴譜

(1760; XVII/168) |

18; RBD; like <1700

Ao Ai Ge |

|

35b. 琴香堂琴譜

(1760; XVII/75) |

18; ZD

Yu Ge |

|

36. 研露樓琴譜

(1766; XVI/526) |

18; RBD; like <1700

Ao Ai Ge |

|

37a. 自遠堂琴譜

(1802; XVII/493) |

18; zhidiao shangyin

Ao Ai Ge; like <1700 |

|

37b. 自遠堂琴譜

(1802; XVII/376) |

18; shangyin

Zha Fuxi pu in GQQJ#1/115; Yu Ge |

|

38. 裛露軒琴譜

(>1802; XIX/275) |

18; ZD

Yu Ge |

|

39a. 琴譜諧聲

(1820; XX/177) |

18L; 清變宮音 qingbian gongyin

Ao Ai; like <1700 |

|

39b. 琴譜諧聲

(1820; XX/163) |

14; 角商 jiaoshang

Yu Ge |

|

40. 鄰鶴齋琴譜

(1830; XXI/71) |

18; NFI

Yu Ge (comes after XXSY but standard tuning) |

|

41. 二香琴譜

(1833; XXIII/170) |

18; 羽音 yu yin; like <1700

Ao Ai Ge; like 1744, says Ao Ai commonly called the "Northern Yu Ge" |

|

41. 二香琴譜

(1833; XXIII/136) |

short afterword; 18; 商音 shang yin

Yu Ge |

|

42. 悟雪山房琴譜

(1836/ XXII/340) |

19; 中呂均 zhonglü yun (ZLY)

Yu Ge |

|

43. 行有恒堂錄存琴譜

(1840; XXIII/202) |

18; has afterword and 眉批 (comments at top of two page)

Yu Ge |

|

44. 張鞠田琴譜

(1844; XXIII/280) |

18; attrib. Liu Zihou and comes after XXSY but standard tuning

宮調商音 gong diao shang yin; has commentary, gongche notes and marginal comments; Yu Ge |

|

45. 稚雲琴譜

(1849; XXIII/418) |

18; RBD

Ao Ai Ge; like <1700 |

|

46. 琴學尊聞

(1864; XXIV/249) |

13; 商音宮調 shangyin gongdiao

standard tuning; Yu Ge |

|

47. 蕉庵琴譜

(1868; XXVI/57) |

18; shangyin

attrib. Liu Zihou but standard tuning; Yu Ge |

|

48a. 天聞閣琴譜

(1876; XXV/381) |

preface and afterword;

ToC: "from 1722"; 18; ZY;

there are lyrics at end XXV/388 (also = 1722) but they are for ruibin version (see next)!; Yu Ge |

|

48b. 天聞閣琴譜

(1876; XXV/457) |

14; yuyin, shangdiao; commentary; "from 1744"

standard tuning; marginal comments, "originally 18 sections...."; Yu Ge |

|

48c. 天聞閣琴譜

(1876; XXV/561) |

18 + 尾音 coda (#15 has comment); RBD; starts like <1700 but then Section 2 adds a descending glissando;

Ao Ai Ge; ToC and margins: "1702", but not there. Recorded by GPH. |

|

48d. 天聞閣琴譜

(1876; XXV/578) |

8!; RBD; "琴苑譜" (almost same as 1670: corrections? Attrib Liu Zihou)

Yu Ge; not the source of the modern short Ao Ai |

|

49. 天籟閣琴譜

(1876; XXI/235) |

18; RBD; like <1700

Ao Ai Qu: "same as the old Yu Ge" |

|

50. 響雪齋琴譜

(1876) |

18; RBD

Ao Ai (Handbook not in QQJC) |

|

51. 希韶閣琴譜

(1878; XXVI/358) |

compare 1722; attrib Liu Zihou; "熟,金二譜合壁"; 18; ZY;

preface, comments between sections, at end adds lyrics of Leji Yin and Yu Ge; Yu Ge |

|

52. 雙琴書屋琴譜集成

(1884; XXVII/304) |

"邗江吳派 Wu School of Han River" (near Yangzhou?); 19 (including 尾聲 weisheng); shangyin

No mention of re-tuning strings; Yu Ge |

|

53. 枯木禪琴譜

(1893; XXVIII/73) |

18; zhiyin

attrib. Liu Zihou; Yu Ge |

|

54. 琴學初津

(1894; XXVIII/292) |

19 including 收音 finale; shangyin

Guess standard tuning (Zha guide mentions no tuning changes for any piece here); Yu Ge |

|

55. 琴學叢書

(1910; XXX/232) |

18; gongdiao shangyin; from 1802

琴府/986; Yu Ge |

|

56. 夏一峰傳譜

(1957; #11) |

18; standard tuning

Yu Ge |

|

57. 虞山吳氏琴譜

(2001, p.74) |

said to follow Wu Jinglue's 1940s reconstruction from 1722; 18

Yu Ge |

|

58. 古琴曲集 II

(pdf)

(2010, Level 8 #6, pp.78-82) |

7; abridged versions of Ao Ai have been popular since at least the 1980s, with quite a few modern recordings. Most seem to be based on this transcription from the Conservatory repertoire Guqin Quji; it abridges Guan Pinghu's reconstruction from 1876 (XXV/561; 18 sections) down to 7 sections. |

|

59. 抄本 (pdf)

(Undated handcopy) |

This abridgement of the Guan Pinghu version is in 9 sections; compared to the 7-section Conservatory version, it splits the first and fourth sections in two, but expands the latter (becoming its sections 5 and 6). Its Section 7 (in harmonics) is like the Conservatory Section 5, but its sections 8 and 9 are somewhat different from the Conservatory 6 and 7. |

Return to the top